Memorial Day has come and gone, signaling the unofficial start to National Parks season — but for people who don't, can't, or simply choose not to drive, many of these natural wonders will remain firmly out of reach.

Since the Yellowstone National Park Act was first signed in 1872 before the birth of the automobile, protected public lands have been a popular destination. Today, though, many of those parks — including Yellowstone itself — are arduous and expensive to access without a private automobile, if it's even possible to reach them at all.

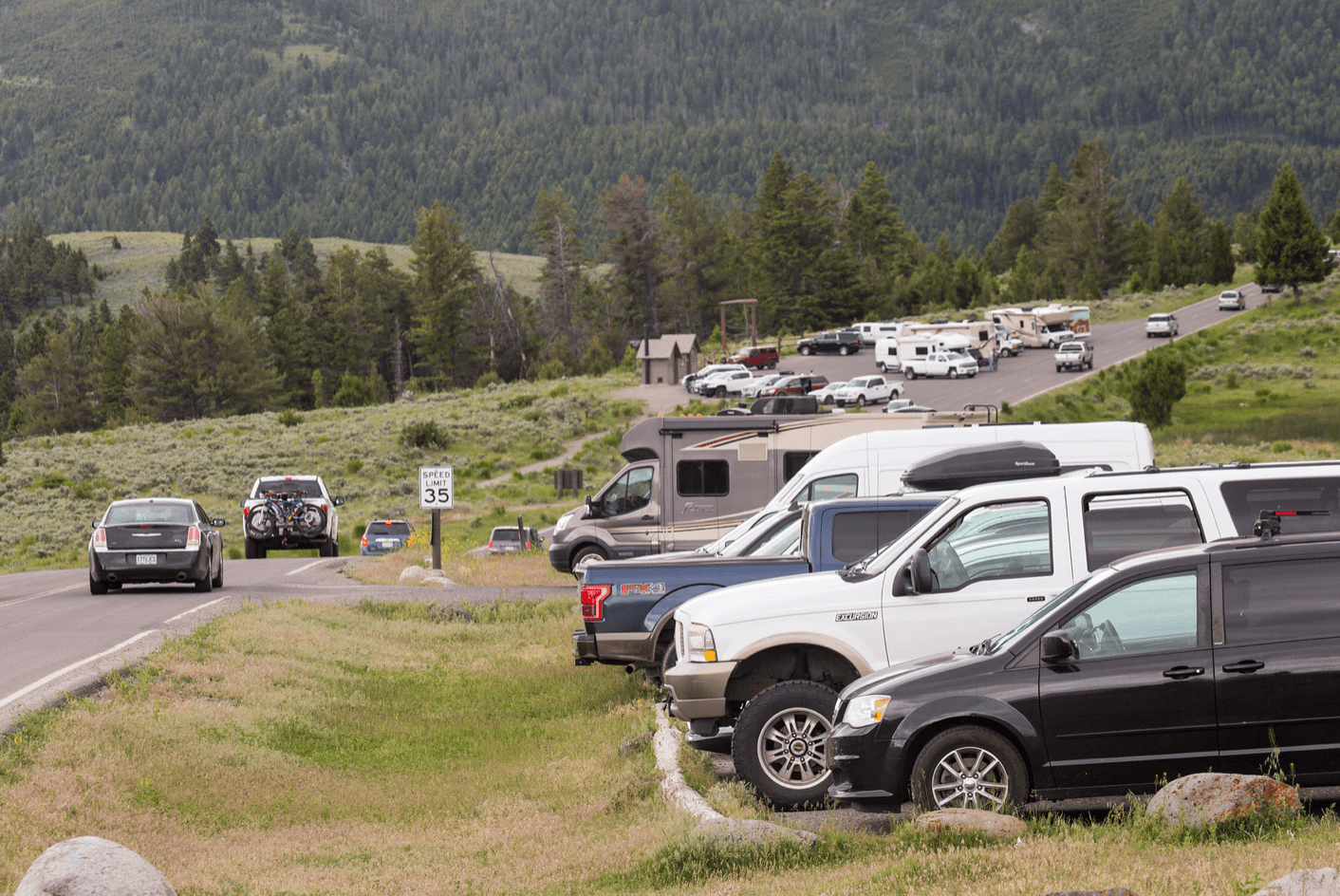

That's particularly troubling in light of the Park Service's ostensible commitment to "actively address the challenge of climate change" — and the impact that excessive driving has on parklands themselves. In 2019, the National Parks Conservation Association estimated that 96 percent of NPS-owned sites struggled with "significant air pollution problems" caused largely by private motorists, despite the fact that many are located in remote areas with few drivers besides park visitors. A stunning 88 percent of parks reported damage to sensitive species and habitats as a direct result, and 85 percent regularly reported air quality levels that could damage human health, too — and that doesn't even account for other forms of car pollution, like noise, road dust, micro plastics from tires, and the salmon-killing tire coatings like 6PPD-quinone.

This one is particularly sad. You can't bike because people driving cars are too distracted. pic.twitter.com/F8kubTS6ZH

— Anna Mumford Zivarts (@AnnaZivarts) May 5, 2022

Those who might at least try to get a little fresh air at a National Park, though, may still be out of luck — if they can't access a personal car.

Apart from expensive private shuttles, many of the 63 major national parks located outside urban areas aren't even served by basic transit to nearby communities, and some require intrepid active travelers to walk and roll along dangerous, high-speed roads with no protection for people outside motor vehicles. Motor vehicle crashes are the second-leading cause of death in national recreation areas, which does not count those who might have lost their lives just steps away from a park's borders. (Accidental drownings top the list.)

That's not to say the National Park Service isn't trying — even if its efforts aren't as robust as they could be. In 2018, NPS partnered with the Federal Highway Administration to release its first-ever guidelines on how community leaders and park staff could better support safe walking and biking, but those recommendations weren't binding, nor were they accompanied by new resources to actually implement them.

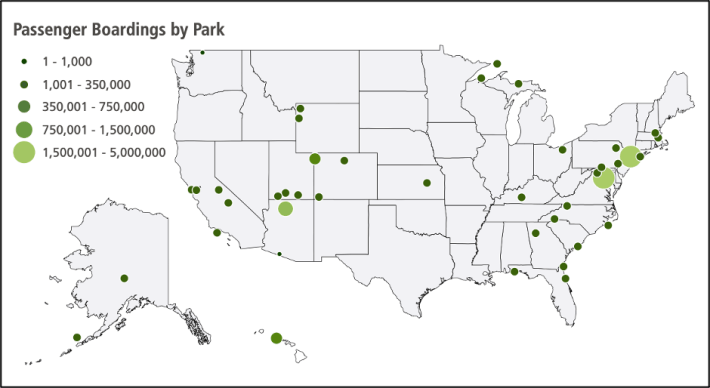

As part of its Alternative Transportation Program, NPS also provides shared transportation options to park visitors, but they're mostly focused on moving people within protected lands and providing educational amenities like guided bus tours, rather than getting folks to and from the park in the first place. The Service currently operates 66 transit systems across 49 NPS sites, mostly through private sector partnerships, but only 16.7 percent of them count "moving people to or from the park" as their primary objective, according to a 2020 report; tellingly, the same report took pains to clarify that while "reducing [vehicle miles traveled] can be a goal of NPS transit systems, it should not be a defining characteristic."

For the 60 percent of people with disabilities who don't drive — not to mention anyone else who can't afford or doesn't want to buy, rent, or borrow a car — that means that enjoying these protected lands is often all but impossible, or at the very least a daunting challenge.

Though no comprehensive analysis has yet been done on how many major National Parks are possible to visit without a private vehicle, an ongoing guide from the car-free travel website OffMetro.com lists just 24 sites among its recommended destinations for car-free travelers. Some, like Arches National Park in Moab, Utah, require those travelers to hike several miles from the shuttle drop-off point before reaching the park itself; others, like North Cascades outside Seattle, require a challenging and often expensive combination of intercity bus or rail, followed by a shuttle and sometimes a ferry. Many park websites don't even bother to tell travelers how they might visit without a vehicle if they're daring enough to try.

By contrast, those same parks typically maintain far simpler road routes for motorists, list driving directions prominently on park guides, and allows visitors with vehicles to park right at the trailhead.

"The NPS is doing a nice job showing travelers how to travel inside the parks without a car, but they can definitely work together with surrounding communities on creating alternative transportation ways for reaching the parks, said Shay Yellin, editor-in-chief of Off Metro. "[Reaching the national parks without a not always convenient or pleasant, or cheap — but it’s definitely an experience that can inspire and reconnect you to the great outdoors."

Yellin emphasizes that NPS is already making important strides towards becoming more multimodal, and that staff "is trying to change the mindset and move away from cars being the main mode of transportation to and in National Parks." The most recently named NPS site, West Virginia's New River Gorge National Park, even boasts an Amtrak stop squarely in the middle of the park that connects travelers from Chicago and New York City with the beauty of nature (though it's still challenging to get to the town nearby without driving, for those who'd rather book a hotel than a primitive camp site on the grounds.)

Still, as America confronts the intertwined crises of climate change, traffic violence, and car dependence itself, Yellin is optimistic that the Park Service will step up and do even more.

"More American families are becoming environmentally conscious and eco-friendly, and it should be the NPS’s responsibility of helping them find eco-friendly ways of reaching our National Parks," Yellin added.