Pedestrian death rates climbed to a 40-year high in 2021, but experts say the factors driving the national traffic violence crisis emerged far earlier — and that policymakers urgently need to confront them.

A staggering 7,485 pedestrians died on U.S roads last year according to new estimates from the Governors Highway Safety Association, an even more horrifying number than the 7,342 deaths the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration projected earlier this week. (Editor's note: GHSA and NHTSA's totals diverge because of differences in their analysis methods, e.g. when a pedestrian falls into a coma and dies at a later date, whether a driver who is killed while standing next to her disabled car on a road shoulder counts as a "pedestrian," etc.)

Both numbers, though, would represent the highest body count since 1982 — and both would rank 2021 in the top 10 deadliest years for walkers since the federal government began tracking roadway fatalities. Of course, that spike didn't occur overnight; deaths of vulnerable road user have increased every year since 2007 after decades of steady declines.

And advocates say that's all the more reason to confront the emergency head-on, rather than chipping away at the death count gradually.

"It is shocking, it is unacceptable, and it should be a wake-up call for everybody," said Pam Shadel Fischer, senior director of external engagement for the Governors Highway Safety Association. "This is a national emergency, and our respond to it cannot be business as usual."

Here are just four of the most prominent reasons why so many walkers are dying, according to GHSA's analysis of the pre-2021 crashes for which the most detailed information is available — and a few thoughts on what to do about it.

1. There aren't nearly enough sidewalks

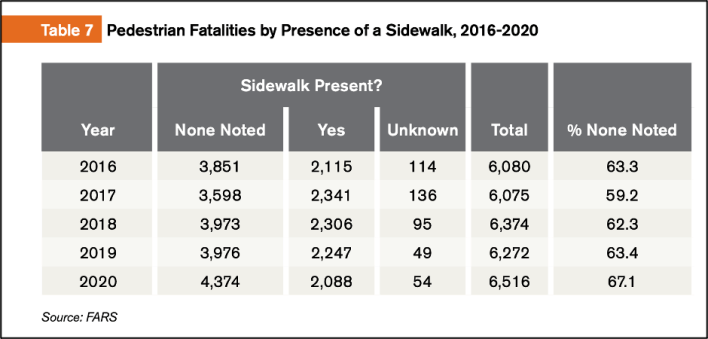

The most obvious way to save pedestrians' lives, of course, is to give them a sidewalk. Over the past five years, though, even this most basic of infrastructure has been absent in an increasing percentage of crashes — and by 2020, over two-thirds (67.1 percent) of walker deaths happened on roads without protected space for people on foot or in wheelchairs.

Notably, those stats don't even account for whether the sidewalks that were present were actually usable at the time of the crash — particularly for people with disabilities, caregivers pushing strollers, or anyone who struggles to a navigate narrow, broken, or obstructed strip of pavement.

Since sidewalk maintenance is largely left up to adjacent property owners, countless U.S. communities fail to comply with even basic ADA standards that would help all of these groups. A self-administered audit in Baltimore, for instance, found that 64 percent of pedestrian paths weren't up to code, and a damning 98.7 percent of the ramps that lead up to them weren't actually passable by people who use assistive devices.

For communities that are subject to heavy weather — which, in the age of climate change, is pretty much all of them — snow and flooded paths provide additional challenges that can easily force a walker into the street.

"It's a real challenge, but it's not impossible," added Shadel Fischer. "The onus is on the DOTs at the local, county, and state level to do these sidewalk inventories ASAP, and give community members the opportunity to use their smartphones to tell their government when there's a problem."

Some advocates might add that requiring governments themselves to do basic maintenance – especially the kinds they already do in the driving lane, like snow clearance — should be an option on the table as well.

2. There are too many ultra-dangerous roads in neighborhoods

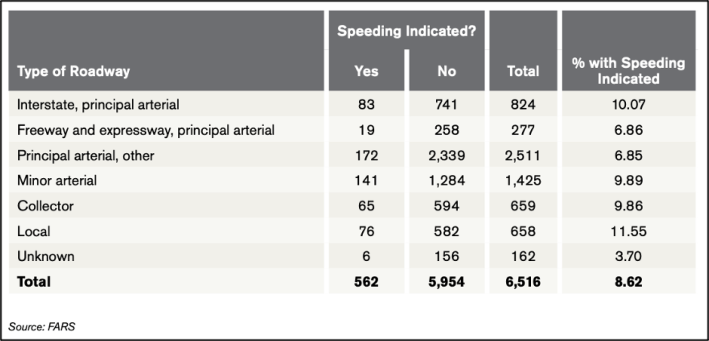

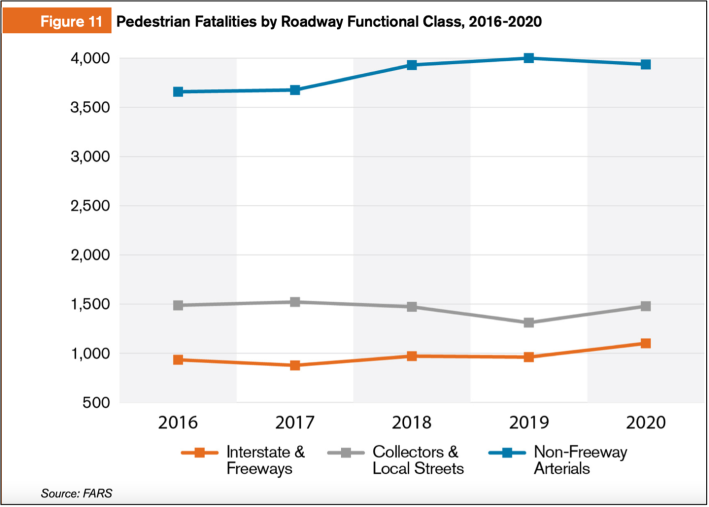

Those sidewalk statistics are even more upsetting in the context of the dangerous streets from which they're missing. The GHSA found that a staggering 73 percent of 2020 walker fatalities happened on roads classified as principal, minor, or interstate arterials, a technical term for high-speed, high-capacity roads in urban areas.

Or, to put it more bluntly: U.S. neighborhoods are full of corridors that run directly adjacent to places people are likely to walk, which are nonetheless designed to encourage driver behavior that is all but certain to kill those walkers in the event of a crash.

Those trends are squarely in line with a landmark study last year, which found that 70 percent of the most deadly roads in America for pedestrians had four lanes or more, and 75 percent had posted speed limits above 30 miles per hour — two design characteristics that are virtually universal among roads classified as arterials.

Notably, the GHSA report pointed out that only six to 10 percent of arterial crashes in 2020 involved speeding — but that doesn't really matter when the speed limits are so high that drivers are all but certain to kill any pedestrians they might strike, even when they're obeying the law. The average walker struck by a driver traveling at 30 miles per hour will die about 40 percent of the time; that rate jumps to 80 percent when the motorist goes just 10 miles per hour faster, and is even higher when the vulnerable road user is elderly, has a mobility challenge, or is struck by a larger vehicle like an SUV or a pick up; arterial speed limits usually range from 30 to 40 mph.

Another common design feature of arterials is the relatively long distance between crosswalks, though police are currently not required to collect data on the proximity of intersection infrastructure — or its quality.

That's particularly troubling because, by 2020, a staggering 67.1 percent of pedestrian fatalities happened at mid-block or along a limited access highway, but police don't collect data on how far walkers would have had to travel to reach a crossing signal, never mind whether that signal was working, whether that intersection was well-lit, or other structural factors that might entice a walker to dash across dangerous driving lanes instead.

GHSA's data suggest that cops should start collecting this critical information — and that communities should put that data to use to redesign roads now. (And that's true for the increase in cyclist deaths over the same period.)

3. The U.S. transportation system is structurally racist

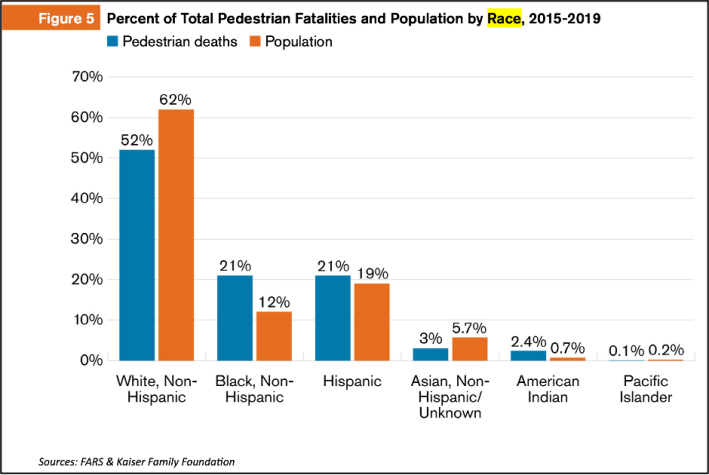

Experts have known for years that Black Indigenous, and Hispanic walkers are significantly more likely to die in car crashes than pedestrians of other races. During the pandemic, though, those disparities grew even more sharp — and experts expect that horrifying trend to continue in 2021.

According the report, an analysis of 2015-2019 crashes revealed that "non-Hispanic Black people represented 12 percent of the population during this time period but accounted for 21 percent of pedestrian fatalities. Hispanics made up 19 percent of the population but were 21 percent of pedestrian deaths. And most astonishingly, American Indians represented 0.7 percent of the population but accounted for 2.4 percent of deaths — more than triple what would be expected if pedestrian deaths were distributed equally among race and ethnicity categories."

State highway agencies don't yet have a full picture of how many people of color died in pedestrian crashes in 2020 and 2021, but the report suggests that "it is likely that BIPOC’s over-representation in pedestrian deaths continued into 2020 and potentially increased."

That's in part because communities of color and low income are disproportionately home to most dangerous roads, and because residents of those neighborhoods — particularly Black women — were most likely to still be required to travel outside the home to work during quarantine, and many of them walked for at least part of their commute, if only to reach a transit stop. The same may be true for children of color, at least in cities like New York.

Add that together with shifts in commute patterns that kept drivers moving fast at virtually every hour of the day.

"We're still trying to wrap our arms around what rush hour looks like today, because it's not the same, even as more people start going back to work [outside the home]," Shadel Fischer adds. "We're not seeing as many people heading out the door to work in their office all at the same time, and when traffic is lighter, people are going to be less mindful of speed ... We're also wondering: have [drivers] developed this mindset of, 'I've survived a pandemic I'm gonna do what I damn well please, and government shouldn't tell me what to do.' That really troubles me as a traffic safety professional."

Until American safety culture can be more comprehensively remade, though, it's probably wise, at the absolute least, to focus America's safety resources on the communities where deaths are disproportionately happening.

4. There are too many SUVs and pick ups on the road

Despite knowing for decades that the biggest cars on the road are also the most deadly to walkers, regulators have stubbornly refused to curb automakers' ability to sell vehicles that disproportionately kill vulnerable road users — and as megacars rapidly become the most popular models on the road, that failure is showing up in America's recent pedestrian fatality numbers

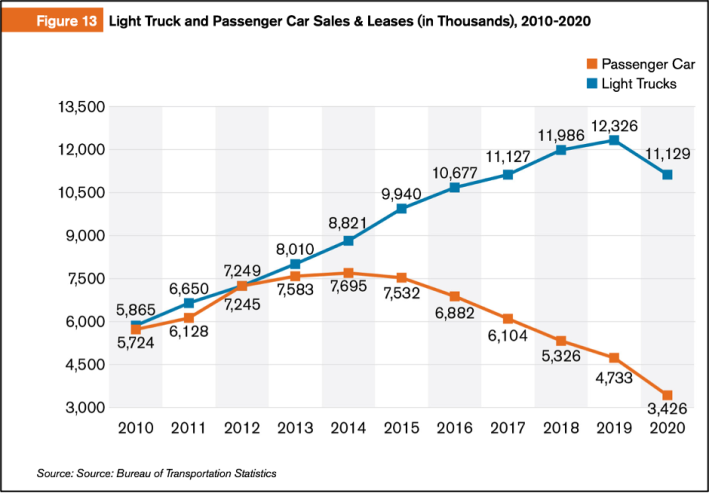

According to the GHSA report, "light trucks" — a vehicle class that includes SUVs, pick-ups and vans — were involved in 39.5 percent of all pedestrian fatalities in 2020, a share that narrowly exceeds the share of crashes involving smaller passenger cars (39.2) Deaths involving SUVs alone increased a shocking 76 percent over the last decade, while deaths involving smaller cars increased just 36 percent over the same period.

Countries like Colombia are already taking aggressive action to make cars safer for people outside of vehicles in response to their own traffic violence surges, and there's no reason why American can't do the same as part of its push to design comprehensively safe roadway systems.

And Shadel Fischer is optimistic that policymakers are finally paying attention.

"I'm hopeful that now, with the new National Roadway Safety Strategy, a real commitment from US DOT, and all the funding coming to agencies to solve this problem, we will have a strong collective response," she adds. "Everyone seems to be saying, 'We have to work together, and the Safe Systems approach is the right way to go.' We've seen what other countries have been able to do by implementing it, and we have a road map to follow. ... Now, I'm just hoping — and I am shouting from the rooftops about this — that we can get the public on board."