There are four types of drivers in U.S. communities, a new analysis argues, and transportation leaders need to adopt distinct strategies to influence each group's behavior on the road — and to get them out from behind the wheel altogether.

In a recent webinar from Portland State University's Transportation Education and Research Center, urban planner and advocate Cathy Tuttle urged professionals to develop a "car master plan" (like the one she developed for her home city of Portland) to quantify how much of their cities' resources and land are devoted to car use, understand the impact of those choices on their most vulnerable residents, and commit to strategies for change.

Countless U.S. cities maintain ambitious bicycle, pedestrian, and transit plans to encourage use of sustainable modes, but without a coordinated document for automobiles, it's often impossible to enact them — because driver-focused projects almost always come first.

"Every transportation plan now is a car-response plan," wrote Tuttle. "Every street is a car street. Every bit of our shared public space is dedicated to car parking, car movement, or preventing car parking and car movement. Portland thrived in the past without cars and can thrive again without many cars in the future. ... All cities need car master plans."

Tuttle's vision of a master plan would not merely acknowledge that cars are dominating city streets but also the specific types of motorists – and non-motorists — who are on the road in the greatest numbers. And much like former Portland Bicycle Coordinator Roger Geller's famous "four types of cyclists" framework, she says cities need to develop specific policies and messaging aimed at four key segments of the traveling public if they want to change the way people get around.

1. The Entitled Driver

Certainly the most visible driver on U.S. roads is what Tuttle calls "entitled" drivers — and not just because they often drive the kind of ultra-huge vehicles that are most fatal to pedestrians, cyclists, and even motorists in smaller cars.

That's because drivers in this category are also among the most likely to drive recklessly or drunk, complain loudly about the already subsidized costs of vehicle ownership, modify their mufflers to announce their presence to anyone within a few blocks, and proudly claim vehicle ownership as their fundamental right, rather than an unfortunate necessity in cities without more mobility options.

Unlike their closest counterpart in Geller's biking typology — the "strong and fearless" cyclist who will ride even in the most dangerous and inhospitable conditions — Tuttle says that Entitled Drivers aren't outliers in Portland, where she estimates they constitute about 25 percent of all residents.

That's in part because U.S. communities often actively accommodate entitled motorist behavior, by designing for dangerously high speeds on neighborhood roads, failing to use policy to disincentivize large vehicle ownership, or even staging photo ops where politicians at all levels of government celebrate aggressive driving and aggressive vehicles.

"The four driver types are definitely a continuum — even people who are just habitual drivers have their entitled moments," said Tuttle. "But there are some people who often take it further. They drive when they're drunk, or they drag race, or they roll coal. Sometimes it's even just as simple as continuing to drive as we get older, long after it's safe for us to do so, even when we have other options."

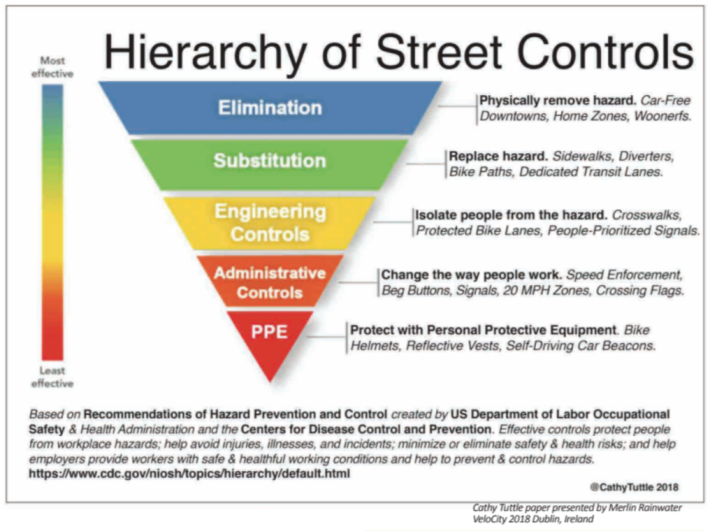

Tuttle's advice to policymakers who want to to influence entitled drivers is simple: design streets, communities, and policies so it's clear, at every turn, that excessive and dangerous driving is unacceptable.

"Outreach to Entitled Drivers is honestly not to appeal to their goodwill, but instead to inform them of clear limits on how and where cars can be used, enforced by regulations," she wrote. "Entitled Drivers — and all car drivers — need clarity about how to share public space."

2. The Habitual Driver

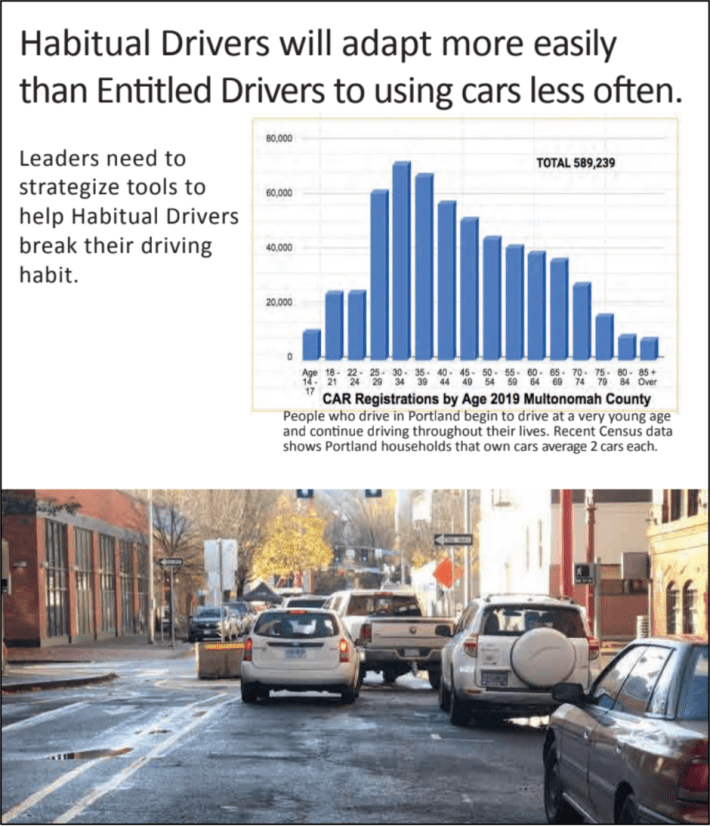

Tuttle estimates that the largest group of motorists on the road (30 percent of Portland residents) are pretty much only there because it's what they've always done — and because they don't belong to a culture that's urged them to question whether there might be a better way to get around.

Tuttle is careful to note that so-called "Habitual" motorists are subject to the same policy and design incentives as Entitled Drivers, and many of them buy dangerous cars and drive them faster than is safe, too. But because their attitude towards driving is different, they're pretty unlikely to do donuts in the middle of the street — and they're very likely to respond to incentives to bike, walk, or take transit when they're presented with them.

"Simply telling people to stop driving, without demonstrating alternatives they see as viable, just makes people stubbornly fight back," Tuttle wrote. "Habitual drivers need more carrots (and targeted information) than sticks."

Tuttle adds that some Habitual Drivers may never totally eliminate their car habit, but they often happily walk, bike, or take transit when doing so seems like the obvious choice — and when driving is at least slightly disincentivized, through accurate pricing of parking, congestion, and the other negative externalities of car use.

"Habitual drivers are people who do what is easiest, they can be more easily swayed if their choices are easy, cheap, and reliable," she said. "They want to be part of a group.They want to act collectively to do their part."

3. The Reluctant Driver

Even in eco-conscious Portland, Tuttle says just 5 percent of the residents only climb behind the wheel when they absolutely have to – but that number could be a lot bigger if the language of car dependency were a bigger part of the transportation conversation.

So-called "Reluctant Drivers," she says, often include people who rarely drive, but can't quite give up a private vehicle altogether because a handful of their most critical and regular trips can't be easily completed without one. That includes people who rely on cars to perform their core job functions but would rather not, people who used to take transit before a critical route was cut, and people who just plain don't want to drive, but don't see a good alternative. Tuttle notes that she's a reluctant driver herself.

"Reluctant Drivers choose to drive only because other transportation options take too much time, cost too much, feel unsafe, or aren’t practical at non-peak hours," Tuttle wrote. "Many Reluctant Drivers simply don’t like driving, [and they] easily switch to other travel modes when they are available."

Tuttle says Reluctant Drivers don't take a whole lot of persuading to get out from behind the wheel, but they do need support to stay there — or they can easily slide towards the "habitual" end of the driving spectrum, just like many of their neighbors.

4. Non-drivers

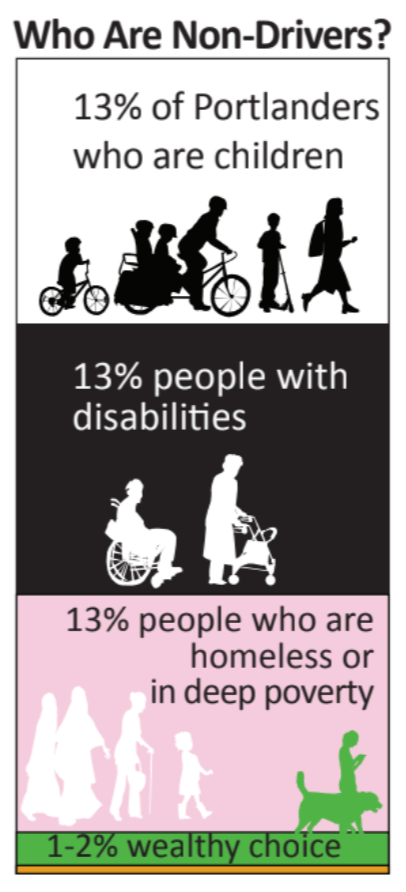

Perhaps the greatest irony of America's car-dominated status quo is just how many Americans don't drive at all — especially when people too young to get licenses are taken into consideration.

Tuttle estimates 40 percent of Portlanders are non-drivers, including children, people with disabilities, and people who can't afford to drive. Just one to two percent of city residents are what she calls "privileged non-drivers of choice."

"When I was presenting this model to some transportation professionals, I did get pushback for including children in the pool of non-drivers," Tuttle added. "My answer to them was, 'Well, kids are people with as much right to the street as anyone else.' ... [These] are people that groups like business chambers and homeowner associations have decided don't have a right to streets because they don't contribute as much to the economic vitality of the city."

Tuttle emphasizes that a good car master plan would be proactive in reaching non-drivers, too, rather than assuming that all of them are happily car-free — or that they'll necessarily stay that way even as cities begin implementing better strategies.

"We want to increase the number of privileged non-drivers of choice, but we also want to think about [improving the mobility of] people for whom cars are an unimaginable luxury, and for whom even transit is too expensive," she added. "And we especially want to think about children who will be able to get into a car when they're 16."

Tuttle emphasizes that her four categories are just a starting point for conversation, and that other researchers should develop their own methodologies for analyzing their own communities — and identifying strategies to win them over.

"Car drivers are not a monolith," she adds. "We used to think that cyclists were just 'middle aged men in lycra'; we've moved way beyond that now. It's really important that we look at people driving cars as a variety of groups that have their own needs, and that [we acknowledge that] it takes different strategies to control and influence them. Simply calling people 'drivers' doesn't cover it."