Drivers did not slow really down after Portland lowered the speed limit in residential neighborhoods, but a new study suggests that the reason is more about road design than driver behavior.

In a recent study from Portland State University, researchers examined what happened in the six months after the Portland City Council finished the process of reducing speed limits in residential areas from 25 miles per hour to 20 mph. In addition to updating the nearly 1,000 speed limit signs the city had already put up, the City of Roses also added more than 1,000 new signs to remind drivers to slow down in places where limits were previously unclear; they also distributed roughly 7,000 yard signs that declared to all road users that "Twenty Is Plenty," as part of an overreaching public awareness campaign.

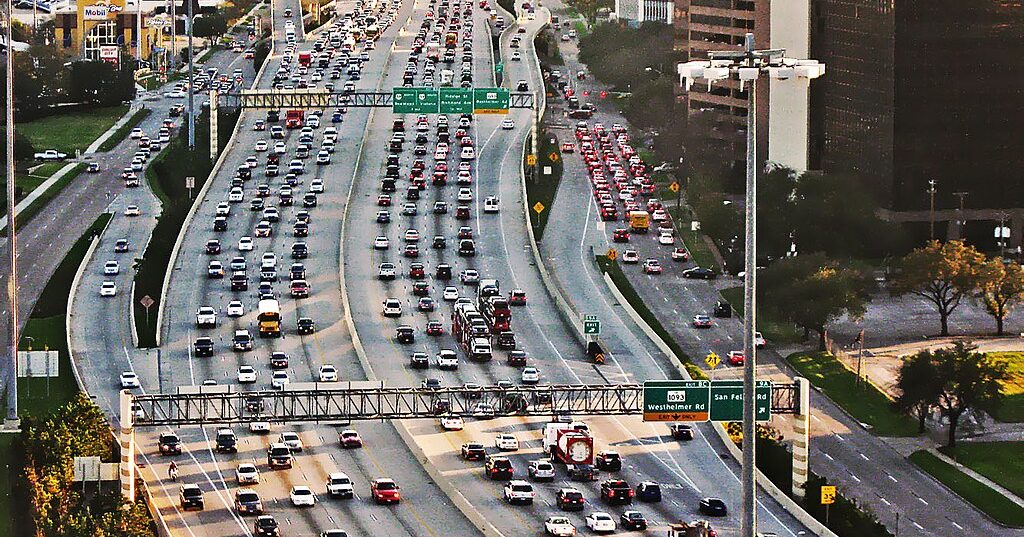

Getting drivers to slow down, though, isn't always easy. The Portland study found that there was no significant change in the median speed of drivers after the speed limit change, and of the 58 individual sites where the city installed automatic traffic counters, only about half experienced a decrease in mean speeds — and on average, drivers only went 1.4 miles per hour slower at those sites than they'd gone before. Meanwhile, Portland police say they struggled to actually enforce the new limits, in part because Oregon law prohibits local leaders from installing automated speed cameras outside of the handful of ultra-dangerous roads included in the city's High Injury Network, which means most residential areas get skipped.

Four years ago Portland, OR reduced the speed limit on residential streets to 20 mph -- and driver behavior barely budged.

— David Zipper (@DavidZipper) February 1, 2022

Moral of the story: Adjusting speed limits isn't enough to change driver behavior; you need to fix street design, too.https://t.co/7dUG0jlPMv pic.twitter.com/KKYFLmtMxq

The researchers behind the study, though, say those findings aren't necessarily surprising — and that doesn't necessarily mean that Portland's signage campaign didn't have an impact.

Even though average speeds barely budged, some of the the speediest Portland drivers did slow down after the new limit signs went up; incidents of cars traveling more than 35 miles per hour were nearly halved (49.6 percent), and incidents of speeding more than 30 miles per hour were reduced by about a third (33.6 percent.) Those impressive numbers, though, were masked by how few high-speed events there already were in Portland's human-centered residential neighborhoods; the percentage of drivers traveling over 35 mph only fell by an average of 0.5 percent citywide.

"I have studied speed limit and speed changes on a wide variety of roads across Oregon — including interstates and rural roadways — and I wouldn’t have expected a significant change just by changing the signs," said Christopher Monsere, a professor of civil and environmental engineering and a co-author of the paper. "But these are already relatively low-speed streets to begin with. It’s just gonna be really hard to see a change in the median speed for such a small speed change with signs alone...[But considering that this campaign took] relatively little investment, it would be a strategy that I would consider for residential streets."

Monsere is careful to clarify that speed limit reductions alone wouldn't have the same impact on roads designed for higher speeds. Mirroring a disturbing trend on roads across across America, a staggering 57 percent of traffic deaths in the Portland happen on just 8 percent of thoroughfares, many of which are wide, multi-lane arterials concentrated in low-income communities of color.

"The pedestrian safety problem is really focused on arterials and not necessarily the residential streets that this campaign impacted," added Monsere. "Just changing speed signs is not going to make an impact there. There's a different toolbox we should look to — modifying signal timing to discourage speeding, redesigning roadway cross sections, things like that. Achieving big changes in speeds on arterial roadways will definitely require other strategies."

Monsere emphasizes that while there's less design work to be done on relatively calm residential streets, there's always more than cities can try — and setting a slow speed limit is a critical first step.

"If I was a city leader, I would obviously look at other strategies about lowering speed — road design, narrowing roadways, speed humps, traffic calming," he added. "But I also would look at this and say, ‘Hey, this isn’t a very big investment, and it did have some impact.’"

Portland, of course, didn't invent the idea of neighborhood slow zones with a catchy rhyming motto. Thanks in part to the "20's Plenty For Us" program spearheaded by the United Nations, cities around the world have recognized the awesome power of the 20 mile-per-hour speed limit, which studies have linked to lower crash rates, lower death rates when crashes do happen, and larger numbers of cyclists on the road, since dangerous vehicle speeds can deter travelers rom getting in the saddle at all. The average 30 year-old pedestrian struck by a driver traveling 20 miles per hour has about a 93 percent chance of survival; at 25 miles per hour, those odds plummet to 75 percent, and they only get worse from there.