A prominent highway safety organization is still pushing enforcement and education in the fight to end roadway fatalities — sparking controversy among advocates of better road design who say that driver behavior is already over-emphasized, and that policing is subject to racial bias.

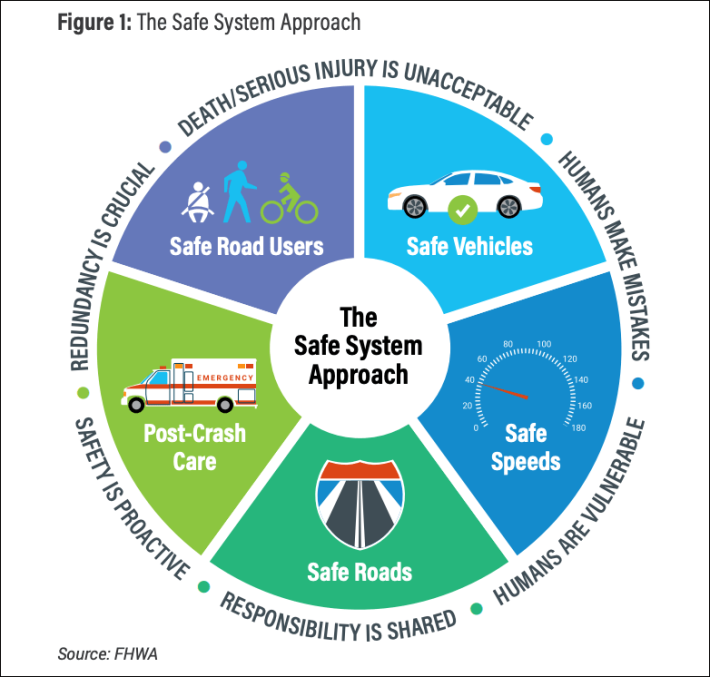

On Wednesday, the Governors Highway Safety Association issued a report which aimed to "debunk the misconception held by some in the traffic safety community that infrastructure alone can end road deaths" and "make the case for the integral role of behavioral safety and road user responsibility in the Safe System approach to traffic safety."

The "behavioral" changes needed are those of #TrafficEngineers. The key to safety is #Engineering roads so people driving /can't/ behave egregiously.

— Bike Tarrytown (@BikeTarrytown) December 15, 2021

That may seem like a hard case to make — at least at first. Long popular in countries with the lowest global rates of roadway deaths like Sweden and Norway, the Safe Systems framework — which treats car crashes as the result of systemic failures that can be solved through a range of systemic interventions — has become beloved among U.S. advocates, in part because it de-emphasizes the education and enforcement initiatives that have long dominated America's approach to road safety.

"The Safe System approach differs from conventional safety practice by being human-centered, i.e. seeking safety through a more aggressive use of vehicle or roadway design and operational changes rather than relying primarily on behavioral changes," wrote the Institute of Transportation Engineers in its technical resources. (Emphasis ours.) "When we take a Safe System approach, we may employ some of our current safety practices, but by taking a human-centered approach we will often make different decisions than we would have otherwise."

The concept gained even more prominence after the U.S. DOT recorded the largest six-month increase in roadway fatalities in its history this fall, prompting the agency to commit to making Safe System the cornerstone of its national roadway safety strategy for the first time. That left organizations like the GHSA, whose stated mission is to "address behavioral safety issues" in the transportation realm, in an awkward position — especially after Congress approved billions in new highway safety dollars under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

"There’s a lot of money and effort that’s going be put into safety in the coming years, and Congress has made it very clear they believe in a Safe System approach," said Jonathan Adkins, GHSA's executive director. "We do, too. We absolutely support safe infrastructure. But we also wanted to get out in front of it and have a discussion about why behavioral safety needs to be a part of our strategy."

Abolish outright, or right-size and reform?

Among sustainable transportation advocates, though, there's seemingly less debate about whether behavioral safety interventions deserve any place in the Safe Systems approach, and more discussion of how big of a role enforcement and education should play — and what forms of each might help restore trust in institutions that have historically used the two most hotly-debated "e's" of Vision Zero in harmful ways.

Especially in the wake of the killings of Michael Brown and George Floyd by police officers, many proponents of Vision Zero have challenged U.S. transportation leaders to radically rethink the role of enforcement in their safety strategies, in recognition of the safety threat that cops themselves can pose to BIPOC road users. The specific vision for those reforms, though, varies from advocate to advocate, from the removal of armed police from all traffic stops, to the removal of armed police, to the removal of all human-based enforcement strategies in favor of automated cameras and "self-enforcing" road designs, and a universe of other possibilities in between.

Debate about the future of road safety education is ongoing, too, though all of the safety leaders Streetsblog spoke with for this story agreed that the most pervasive campaigns, like the "distracted walking" PSAs perennially issued by state DOTs, seem to do more harm than good.

"There’s broad agreement that the behavioral interventions have a place, but frankly, for the last hundred years, their prominence hasn't been seriously questioned — and along the way, the importance of road design and speed management has been really devalued," said Leah Shahum of the Vision Zero Network. "We already see too many education campaigns supported by public dollars that are really just putting the blame on people walking for their own deaths, because they're not, say, wearing bright enough clothes or carrying a flashlight. That’s really inappropriate, and honestly, it's dangerous."

Adkins resists the idea that behavioral safety has been over-emphasized by American transportation agencies, pointing to the infrastructure-focused Highway Safety Improvement Program, which he says receives roughly five times as much funding as NHTSA's behavioral safety initiatives. (The way that states actually use that HSIP money, of course, hasn't always resulted in safer roads, and until recently, states were actually allowed to set safety “goals” that would have meant more people outside cars would die on their streets than in the year before, and still qualify for federal funding.)

And he also maintains that even on the safest roads and in the safest cars, some drivers will still behave dangerously — and when they do, they deserve punishment.

"If someone makes a mistake while they're walking, they shouldn't lose their life because of it," said Adkins. "But something like drunk driving isn’t a mistake, and we can’t accommodate that behavior. We have to root it out through the criminal justice system — at least until we develop vehicle safety technology that can do it for us, and that's still 15 years from being common on our roads."

Some advocates, though, say deadly crashes can be avoided through good design, even when the driver is committing a particularly heinous roadway crime like DUI. A line of well-placed bollards, for instance, may not deter a drunk driver from getting behind the wheel in the first place, but it could prevent him from driving into a bike lane and killing someone other than himself. Putting a convenient and affordable train or bus rapid transit route between the bar and his home, meanwhile, could be even more impactful.

"When we talk about drunk driving, I always say, 'Well, what about the land use?'" said Don Kostelec, a Boise-based planner and safe streets advocate. "When we put drinking establishments along auto-centric corridors, we're essentially prompting drunk driving, because people have fewer options to get to these places; stationing an officer there doesn't actually solve that problem...At the end of the day, the reason why infrastructure deserves the vast majority of our attention is that road design effects 100 percent of road users 100 percent of the time, and even the best education and enforcement campaigns only impact some road users some of the time."

Kostelec acknowledges that there will always be outliers that infrastructure can't solve; after all, even when Norway famously (almost) achieved Vision Zero in 2019, one driver still died when he crashed into a fence. But he says putting education and enforcement first still isn't the answer.

"Sure, behavioral components can address that last small percentage of situations for which the road design piece is, for whatever reason, less effective," he adds. "The problem is, we’ve lead with education and enforcement for so long — which is why we’re in this mess. "

Breaking down silos

The GHSA and its critics do agree that everyone will have a role to play in making the Safe System approach work in America — and that it will take breaking down some of the walls safety professionals have erected between the traditional five "e's" of traffic safety approach.

In an informal poll of Streetsblog readers, for instance, less than half of respondents agreed to the statement that "infrastructure interventions alone" can end roadway deaths in America, eschewing all enforcement and education strategies. But of those who said "yes," several separately clarified that they did support efforts like automated speed cameras, which they thought of as a piece of infrastructure rather than pure enforcement.

Is a speed or red light camera "infrastructure" or "enforcement"?

— Jessie Singer (@JessieSingerNYC) December 16, 2021

I'd argue it's the former, not the latter, because it functions as a guaranteed behavior control, like a narrowed street, rather than a random threat of control, like a cop who happens to catch the offender.

The GHSA report itself points out several ways that behavioral safety specialists can adjust their approach for the Safe System age.

Rather than, for instance, using PSAs to shame pedestrians out of walking outside crosswalks — something even the Government Accountability Office says hasn't been proven effective — the Association says state highway safety offices could educate the public on the benefits of life-saving pedestrian infrastructure like HAWK signals, and help build political support for their local leaders to install more. Police, the report suggests, could be deployed not just to scare drivers into hitting the brakes for a short while — a practice that some studies show isn't a reliable crash deterrent anyway – but to conduct road safety audits that could be used to prevent collisions before they happen.

And as "automated vehicle technology" (and all the confusion about what that phrase actually means) proliferates across U.S. roads, behavioral safety specialists could also help bust myths perpetuated by automakers who would sell a car equipped with a "full self-driving" program that can't actually operate in all situations without a vigilant human driver standing at the ready to take control.

Whatever new forms of education and enforcement arise, advocates say it's critical to keep talking about the role they should play in the Safe Systems approach — and to never forget what advocates have already learned from America's far-too-bloody roadway history.

"Look, education isn't going away," said Mike McGinn, executive director of America Walks. "We’re still going to tell drivers to be careful, and kids to look both ways before they cross the street. But if the last 100 years have taught us anything, we should know that's not enough."