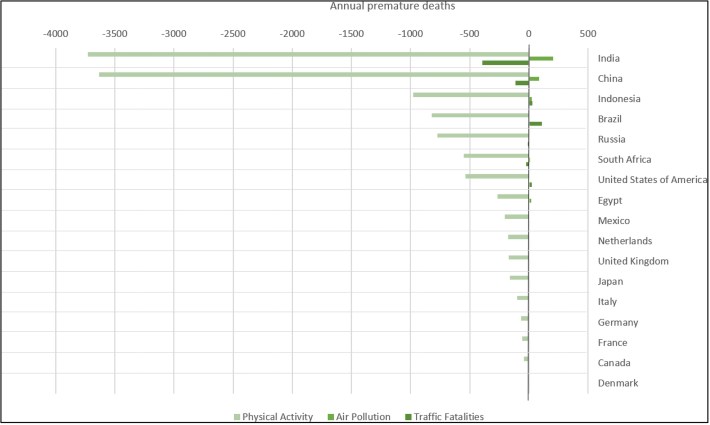

If U.S. leaders take aggressive, but realistic, action to replace car trips with bike trips by 2050, they could prevent more than 15,000 premature deaths every year — and not just in traffic crashes, a new study finds.

In the first study ever to model the comprehensive global public health impacts of the mode shift to cycling, researchers at Colorado State University and a coalition of Spanish universities explored two very different transportation futures for 17 countries. Then they estimated how many lives might be saved by each approach as residents shift (or don't) from sedentary modes to life on two wheels — and how many might be lost to traffic violence and diseases caused by inhaling air pollution along the way.

In the first possibility, which the researchers referred to as the "business-as-usual scenario" — i.e. if global transportation policies remain roughly the same — rates of premature deaths caused by car crashes, air pollution and sedentary diseases caused by driving will, unsurprisingly, remain pretty much the same as they are now in most countries.

The second possibility, though, was based on the famous "Global High Shift Cycling Scenario," a 2014 model that quantified how often people in various countries around the world could, conservatively, be expected to bike, walk, and use transit if their leaders adopted a range of progressive transportation policies. (Think adding comprehensive bike infrastructure, and eliminating fuel and parking subsidies for drivers.) And if 100 percent of those estimated new biking trips were to replace car trips by 2050, the Colorado State researchers say a staggering 205,424 premature deaths around the world could be prevented every single year — and roughly 15,000 lives would be saved in the United States alone.

Even if just 8 percent of those new bike trips replaced journeys in a car — an extraordinarily conservative estimate, considering that in this hypothetical world, every urban area in the world would be outfitted with Amsterdam-levels of bike lanes — researchers say that 18,589 lives could be saved across the globe, 1,227 of which would be in the U.S. alone. That would mean erasing the roughly 850 cycling deaths that occur here every year, plus hundreds of other deaths caused by inactivity and air pollution.

"Even in those countries that we normally consider more risky in terms of air pollution like India and China, the benefits of biking outweigh the risks," said David Rojas, a professor of epidemiology at Colorado State University. "And that was true in every single country we studied."

That finding debunks a perennial myth among active transportation opponents that the public health benefits of biking, like reduced sedentary lifestyle diseases, might somehow be cancelled out by the mode's public health concerns, like increased rates of diseases caused by breathing polluted air — a particular concern among developing countries with high rates of industrial emissions. Those arguments were particularly prevalent following the recent COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, which advocates say gave countries with lower rates of industrial emissions, like the U.S., political cover to focus exclusively on global climate commitments like increasing electric vehicle adoption, rather than on adopting mode shift targets which the advocates say every country needs.

"When we talk about transportation, we have goals for global emissions reductions," added Rojas. "We need to talk about reducing bad health outcomes, too."

Rojas is careful to note that his study doesn't capture all the public health benefits of biking, because it doesn't capture how many drivers' lives would be saved by re-ordering the global transportation hierarchy, or all the walkers, wheelchair users, transit riders, and other road users who would be spared, too.

"This study is very specific to [the public health benefits of] bike use, but of course, improving mobility overall has additional benefits — like achieving Vision Zero for everyone else on the road," he added.

Of course, all those other travelers would experience their own health benefits from a car-light world. In addition to the impacts modeled in his study, Rojas points out that bikeable communities typically have more green space, more real estate to devote to affordable housing, healthy food providers, and other essential services in every neighborhood, and lower levels of noise pollution, all of which have an impact on the physical and mental health of their residents. A mountain of studies have quantified the monumental health savings that follow public investments in sustainable transportation.

"We need to work together and not forget that improving mobility in cities and transportation is not only about traffic safety; it’s also about all the other opportunities to improve health outcomes," he added. "This is something we can decide to change, and it’s the right time to change it."