Four Ways ‘Automobility’ Shapes Our Lives — Besides Crashes and Climate

12:01 AM EST on November 16, 2021

Even the best crosswalk highlights just how much of the rest of the road has been given over to drivers — and how profoundly automobility has infected global culture itself. Image: Piqsels, CC

The violence of car culture extends far beyond the obvious outrages of car crashes, pollution, destroyed communities and structural racism — and until we contend with the more fundamental ways that “automobility” shapes our society, we may never truly end it, a fascinating new paper argues.

In a thought-provoking analysis published in the latest issue of Mobilities, researchers Robert Braun and Richard Randell from the Institute for Advanced Studies in Vienna looked beyond the traditional built environment disciplines and into the realm of philosophy to explore how automobiles have silently gained a stranglehold on the very order of modern society and the imagination of everyone who lives in it.

That story has had countless villains — and even more victims. Worldwide, traffic violence claims another life once every 25 seconds, a death toll that totals more than 3,700 human beings lost every day, and which eclipses all other forms of violent death, including wars — a horrifying burden which fall disproportionately on people of color, people with low income, and society's most vulnerable members. Another 385,000 people die premature deaths from health conditions caused specifically by automobile pollution, in addition to countless fatalities caused by the automobile's leading contributions to climate change.

And the researchers argue those aren't the only ways that automobile dominance kills — and that it corrodes the quality of collective human life even more.

"When most people think of automobile violence, they think of the car itself," said Randell. "What we’re trying to do is get away from that, and talk about the creation of a world where a 'road' is a place where you can be killed without a homicide being committed — and where all these other kinds of violence happen every day because of the larger forces of automobility."

Randall and his co-author argue that reckoning with automobility itself, rather than just its devastating effects, is every bit as essential as holding automakers, policymakers, and other agents of car culture accountable. Because if we don't, those agents will just change the rules of the game and learn to dominate modern life in new ways — and to some extent, they're already doing it.

"Automobility is a totalitarian system which perpetuates multiple forms of violence, and that system is expanding in multiple ways," said Braun. "When you read the economics section in the newspaper, it’s all about automobility and how great it is for a neoliberal economy. When you turn on the TV, you see ads from automakers; even art museums have whole exhibitions devoted to car design. Right now, automobility is expanding into air; aerial mobility may be the new kid on the block, but it’s not by accident that Elon Musk is running Tesla and trying to run private space travel to Mars. ... It's about claiming whatever space it hasn't already dominated."

Here are four fundamental ways that Braun and Randell say car culture shapes our lives for the worse — and a few thoughts on what to do about it.

1. It redefines what roads are for — and which deaths are acceptable

Perhaps the only thing more shocking than the sheer number of lives that car-dominant transportation systems take every year is how many people seem to think those deaths are a price worth paying.

Braun and Randell call this the "moral economy of automobility," which convinces everyday residents that "the ostensible benefits of automobility on one side of the moral equation — speed, efficiency, convenience, excitement, etc. — outweigh the violence on the other side of the equation."

That collective persuasion happened more quickly than many might assume. At the 1896 trial of the first driver to kill a pedestrian in recorded history, the coroner famously said that he hoped "such a thing would never happen again" — right before the jury delivered a verdict of "accidental death," effectively exonerating both the driver and the systemic forces that created the conditions for the killing.

The United Kingdom, where the historic crash occurred, had raised the nationwide speed limit just weeks earlier — one of the earliest examples of the many ways that automobility would come to redesign and redefine the thing we call a "road" as the exclusive realm of drivers.

"For automobile crashes to be understood as 'accidents,' we really had to change what a road was," said Braun. "Before, the road was a place where children played, where people sold things, where all kinds of human activity happened. But when drivers monopolized that space, it turned the road into a thoroughfare and nothing more."

Once the public began to see roads as a space where they had a right to go fast — so long as they were behind the wheel of a multi-ton machine — it was easy to write off roadway deaths as unfortunate "accidents," rather than crimes that had been committed against them in a community space where they have a fundamental right to safety and survival.

"There is no one moment when [traffic violence became excusable]," added Randell. "Car manufactures, advertisers — lots of people have always framed the car in terms of what it gives to people: the freedom to go anywhere, to right to speed, the pursuit of a good life. All of these messages worked together, and over time, it successfully coerced people into accepting violence as something normal."

2. It erases the legacies of its own violence — and the lives of its victims

Every year, governments erect and maintain new monuments for the victims of war and other kinds of violence — but people who die in car crashes rarely receive the same kind of formal public remembrance.

Braun and Randell say that's just one way that car culture perpetuates "epistemic violence" against the public at large, in which powerful interests work quickly to clean up crashes and erase any evidence of death, along with the lives of victims and the grief of the people who survive them. Journalists are trained to report car crashes in two-column-inch articles based on scantly detailed (and often deeply problematic) police reports, rather than honoring the lives and legacies of the dead and probing the systemic causes of the crashes that claimed their lives; ad-hoc roadside memorials like ghost bikes rot in the rain or are removed to prevent potential traffic hazards; movies and television sensationalize car crash as acts of God that begin and end in a few bloodless, fiery instants, if they aren't treated as convenient narrative devices that happen completely off screen.

"There’s definitely a concerted effort to hide the violence of car culture and its effects from us," said Randell. "If it wasn’t so invisible, if we saw it all the time, then automobility would perhaps be more difficult to reproduce and sustain."

That's part of why campaigns to improve crash reporting and properly commemorate the lives of victims of traffic violence victims are so critical — and why the loved ones who survive them are so tireless about making sure their names and stories are never forgotten.

3. It convinces us all our problems can be solved by more cars

No country has ended roadway deaths through vehicle safety improvements alone — though that doesn't mean the forces of automobility haven't tried to convince humanity it's possible.

Braun and Randell argue that the automotive industry and the governments that support it have always claimed that the next technological fix will finally solve the negative externalities of car dominance — until that technology itself creates new problems.

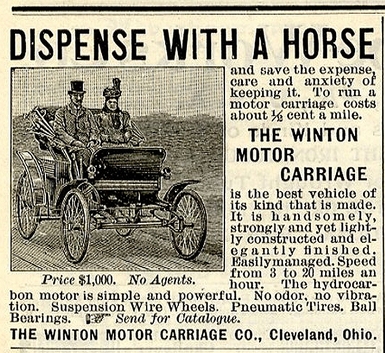

"A lot of people don't know that early cars were advertised as a green solution, because at the time, horses were very dangerous, and horse manure was filling up the streets and causing health problems," said Braun. "[Automobility is still sold as] the only path to a good life, and within that one good life, some small things can always be adjusted. Maybe we change from fossil fuels to a different propellent; maybe we replace the driver with AI. But that narrow definition of 'the good life' doesn’t change, and violence — especially slow violence, like health problems from particulate emissions, or the perils of raw material extraction to make EV batteries — still harm us."

Of course, the researchers don't claim that electrifying cars or making them safer with new technology aren't worthy of public and political support. But over-focusing on technological fixes can come at the cost of low-tech solutions that are proven to save lives and the climate — and it does nothing to stop automobility from becoming even more entrenched.

"It would be a wonderful thing if we could make all new cars electric, and AVs can make a difference," added Randell. "But at the end of the day, it’s basically the automobile industry and its associates saying, 'Great news! You don’t need to worry anymore! We’ve found a solution!'...To replace the world’s fleet of automobiles with EVs and AVs will take decades, and in the meantime, it’ll lead to more automobility — and people will continue to die."

4. It convinces us it doesn't even exist — and only individuals are to blame

Perhaps the most insidious thing about automobility is how few people even know about it — even among advocates passionate about ending its worst impacts.

By now, car culture is so deeply rooted in most global cultures that Randell and Braun argue that it's achieved the status of what theorists call a "hyperobject," or a force so enormous and omnipresent in our lives that humans can't completely comprehend it, even though it shapes almost everything about how we live, move, and exist in the world. Climate change is a classic example of a hyperobject, and the researchers say automobility has just as many deniers, particularly when it comes to its role in creating the global traffic violence crisis.

"There’s this acceptance in the road safety community that 93 percent of crashes are the result of human errors among drivers," said Randell. "But cars are involved in 100 percent of all crashes...In traditional road safety research, when we assign blame for a crash, we tend to point to one of three things: the driver, who made the 'error'; the environment, by which we mean things like slippery roads or broken street lights [rather than roads designed to induce speed]; or the vehicle, at least when it's defective in some way. Certainly some agents of automobility are more responsible that others, but notion of the hyperobject is basically saying, 'Look: it’s all of it. It's this larger thing called automobility, and that's what's killing people."

A real reckoning with automobility, advocates argue, wouldn't prevent crashes just by fixing broken streetlights, taking the licenses away from a few bad drivers, or recalling a handful of defective car models — even though all those things can help. It would reimagine the entire world to put the safety, comfort and dignity of the most vulnerable back at the top of the transportation hierarchy — and restore the physical space that they lost to automobility, too.

"It sounds radical, but the many violences of automobility are similar to the ideas behind settler colonialism," added Braun. "Automobility is another way of colonizing space, and it's happening across the globe. We're taking away land in the road space where it's assumed that no one valuable lives and nothing valuable is happening, [and imposing] a specific hierarchy between the automobilized and non-automobilized humans...It goes far beyond the car, beyond the auto manufacturer, beyond the driver. It's a whole way of life."

Kea Wilson is editor of Streetsblog USA. She has more than a dozen years experience as a writer telling emotional, urgent and actionable stories that motivate average Americans to get involved in making their cities better places. She is also a novelist, cyclist, and affordable housing advocate. She previously worked at Strong Towns, and currently lives in St. Louis, MO. Kea can be reached at kea@streetsblog.org or on Twitter @streetsblogkea. Please reach out to her with tips and submissions.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog USA

The 30% of Non-Driving Americans Must Form a Movement: A Conversation with Anna Zivarts

"At the end of the day, there are going to be folks who still can't drive and can't afford to drive — and there are still going to be a lot of us."

Thursday’s Headlines Fight a Suburban War

The way Politico lays out the battle lines, it's not just drivers versus transit users, but urban transit users versus suburban ones.

How Car-Centric Cities Make Caring For Families Stressful — Particularly For Women

Women do a disproportionate share of the care-related travel their households rely on — and car-focused planning isn't making matters easier.

Wednesday’s Headlines Build Green

A new bill dubbed "Build Green" would replace many of the climate-friendly elements Sen. Joe Manchin insisted on stripping from the Inflation Reduction Act.

E-Bikes and Creating Financially Sustainable Bike Share Programs

The number of customers using bike share in the U.S. and Canada is now at an all-time high thanks to e-bikes.