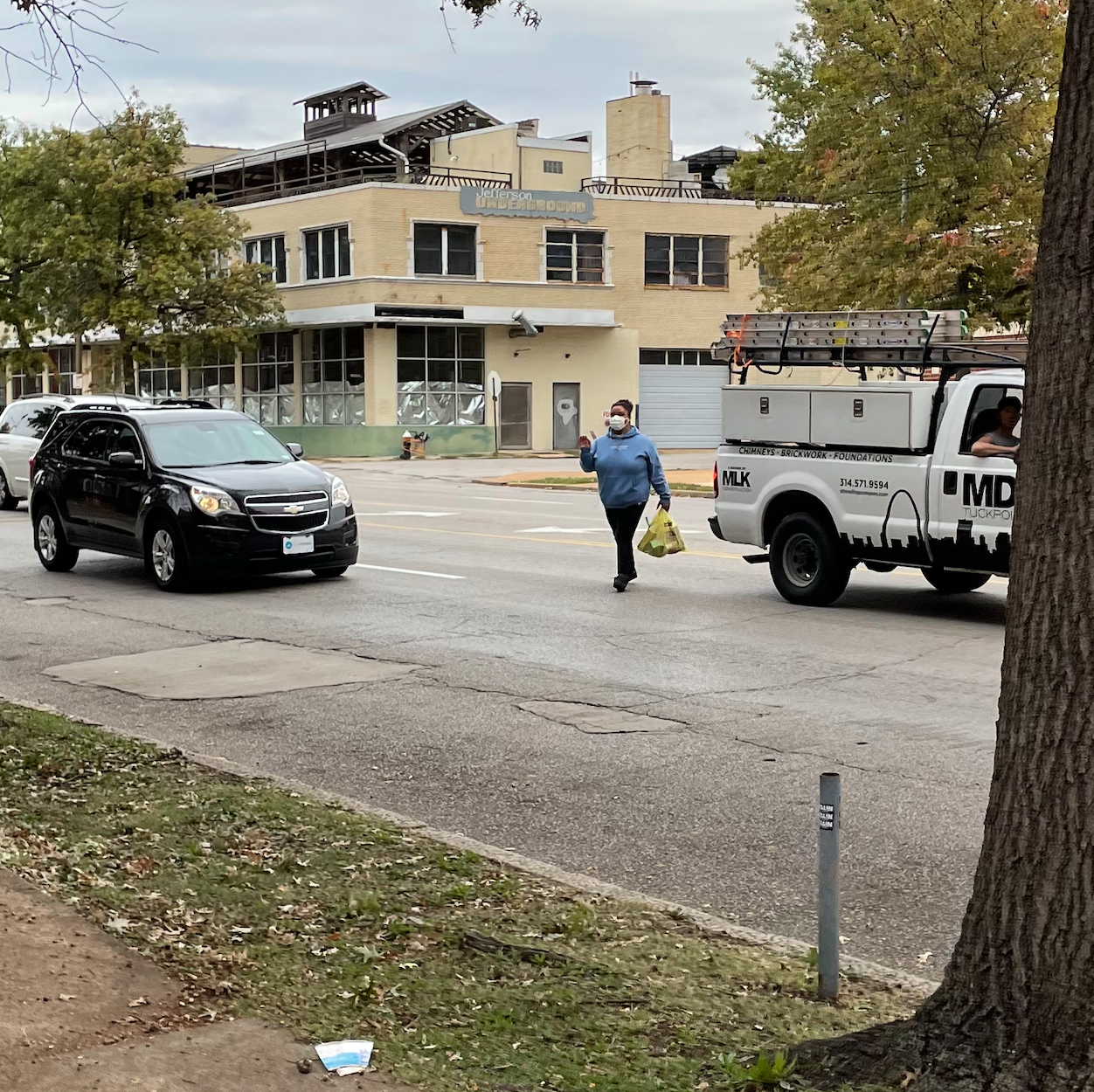

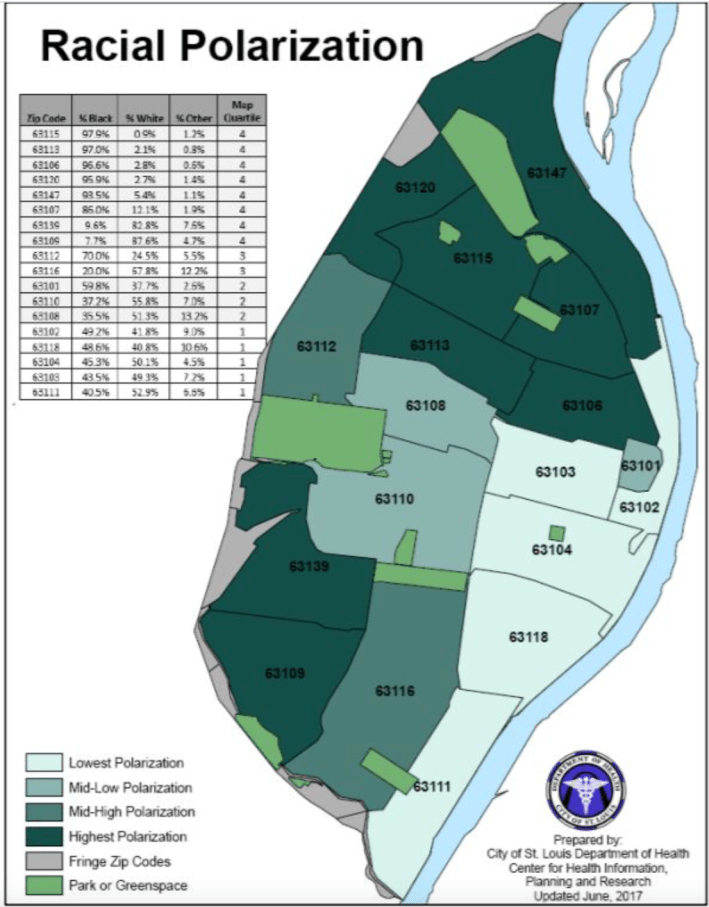

A wave of fatal pedestrian crashes concentrated in disproportionately Black neighborhoods of St. Louis has local advocates questioning a transportation system that continually fails to protect walkers — and local leaders' decision to emphasize police enforcement over infrastructure change, even in the wake of the murder of Michael Brown.

According to Missouri State Highway Patrol records, a staggering 10 walkers have died on the streets of the Gateway City in just 11 weeks, bringing the 2021 death toll to 17 lives lost in a community of just over 308,000 people. That's a rate of 5.5 dead walkers so far this year per 100,000 city residents — roughly three and a half times the national annual average, with two months still left in the year.

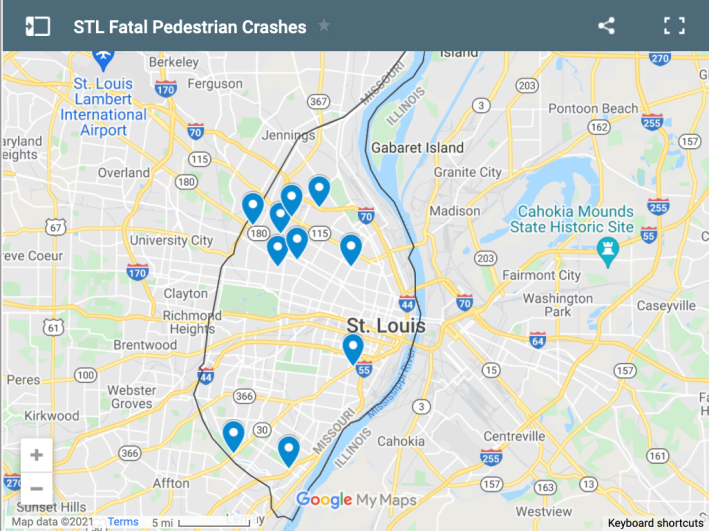

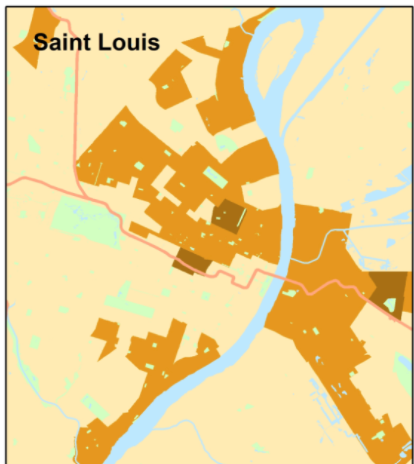

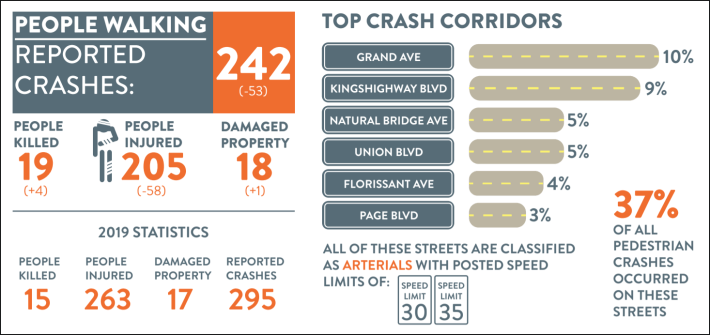

Worse, the death sites have followed an all-too-predictable pattern: clustered on the city's predominantly Black and low-income north side, along just a handful of major high-speed arterials and one-way residential streets that leaders have continually failed to redesign, despite the fact that those corridors have been among the most common sites of pedestrian fatalities for years.

Despite the clear need for intervention, many of the city and state departments that govern the most dangerous roads in the Lou have so far been silent about the rapidly accelerating crisis — and the ones that have spoken up have answered with little more than the promise of more law enforcement officers at high-crash intersections, many of which are located in communities of color that are already subjected to the highest rates of police killings in the nation.

Now, advocates say that walkers are overdue for more holistic and lasting solutions.

"Traditionally, people in St. Louis haven’t been exactly knocking down the doors of City Hall to make it safer for people walking," said Jacque Knight, a St. Louis-based planner and chair of the city's community mobility committee. "And you can't really blame them. But now is the moment we really need that movement to coalesce, because we really need something to change."

Deadly Deja Vu

St. Louis certainly isn't the only U.S. community whose quarantine-prompted traffic violence surge extended into 2021. Nationally, pedestrian deaths rose 22 percent in the first half of 2021 compared to the same ultra-dangerous six-month period in 2020, a phenomenon that experts attribute to a rise in reckless driving and traffic patterns altered by the rise of remote work, which have effectively erased the morning and evening rush hour in many communities and replaced it with all-day traffic that's significantly faster than traffic jams of the past.

But while commuting behavior may have shifted in the Missouri metropolis, the locations of this year's pedestrian deaths are eerily familiar in a few key ways:

- As in years past, seven out of 10 of the recent fatalities occurred in the city's 98 percent Black and overwhelming low-income neighborhoods north of the infamous Delmar divide, which is considered one of the starkest markers of racial polarization in America. (The north side was the site of 74 percent of the 15 pedestrian fatalities that the city suffered in 2020 as well.) In most north side census tracts, between 25 and 50 percent of occupied households don't have access to a private automobile.

- Six of the crashes — five of which happened in North City — involved hit and run drivers, most of whom have still not been apprehended. (In one particularly horrifying incident, the victim's body lay in the street for more than an hour before she was discovered.) Bucking national trends, only one of the four drivers whose cars were identified was driving an SUV, truck or van.

- With the exception of the deaths of two pedestrians who attempted to cross interstate highways carved through their neighborhoods, every crash was within two blocks or less of a bus stop.

- Eight crashes happened on arterials or highways with four lanes of traffic or more, and speed limits of at least 35 miles an hour — two factors that have been known for decades to accelerate walking deaths, but still feature prominently in road designs throughout the Gateway city. Several of those wide, fast roads — including North Grand Boulevard, Page Avenue, and Union Boulevard — are consistently flagged by local advocates as some of the the most frequent site of crashes that injure walkers.

- Two crashes happened on narrower one-way streets, which experts have also noted are heavily conducive to speeding, even when they have fewer lanes.

No Vision to End Traffic Deaths

Advocates, though, may be among the only ones in St. Louis pointing out these glaring trends – much less finding ways to reverse them.

Unlike many of its peer cities, St.Louis city government makes no effort to update a formal, publicly viewable High Injury Network map outlining where crashes continually occur. Nor has the local government adopted a Vision Zero goal to end traffic deaths on city roads by a specific date, or a comprehensive pedestrian master plan to target the accelerating death toll.

The city did adopt a Pedestrian Safety Action Plan in August 2013, but the performance measures outlined in the document aren't binding, and advocates say they're not backed up by the kind of holistic vision or funding that a systemic public health crisis demands. Walking deaths have doubled in the eight years since the plan was adopted.

"It’s not the robust and significant plan or document that says, 'Here are high crash corridors, here’s where the greatest need is, here's when we'll fix it,'" said Kevin Hahn, policy manager for Trailnet, the local active transportation nonprofit. "There's a goal to move towards zero deaths, but the plan that they have is very much still within the system we've got now."

That system, Hahn says, is itself a structural barrier to saving walkers' lives. Unlike other comparably-sized metros, St. Louis allocates much of its street improvement funds directly to 28 members of its board of aldermen — St. Louis's equivalent of a city council — using a formula based on ward population. Hahn says that effectively fragments much of the city's pedestrian planning efforts, sometimes allocating disproportionate traffic-calming resources to the neighborhoods that need them least. Alderpeople are also given significant say over how that money is spent, whether or not they have a planning background — and most of them don't.

Alders are not traffic engineers. They should not be closing streets, locating speed bumps, installing stop signs, or experimenting with “traffic calming.” Empower the streets department to systematically plan for the city and then get out of their way. https://t.co/31GywCQok2

— Chris Prener (@chrisprener) September 26, 2021

"That ward capital system means that a small, densely populated ward with a high number of residents but fewer lane miles of streets sometimes has the same rate of funding that has more lane miles per person," Hahn adds. "And while the alderpeople are working with [transportation professionals at] the streets department, often the department will defer to the wishes of that alderperson [about what kind of intervention goes in,] so long as it meets basic criteria, like, 'can a fire truck fit through here?' So what we’ve seen, historically, is that when a person gets killed at an intersection, the answer is, ‘oh, I guess we need to put up stop signs.’ It's a really reactive approach."

Worse, many ward boundaries lie along the center lines of the city's most dangerous traffic corridors — including six of the 10 sites of the most recent crashes — forcing concerned alderpeople to negotiate with the leaders of neighboring wards in order to make any improvements at all. And most of the largest arterials are also technically owned by a state department of transportation whose primary performance measure is level of service for drivers, which adds even more obstacles to creating meaningful change.

"It gets really easy for to alderpeople say, 'It’s too expensive, it's too complicated, I’ve got limited resources and time. I’m gonna focus my energy elsewhere in the ward,'" said Hahn.

Hahn isn't the only St. Louis advocate who would like to see the city ditch the worst elements of the ward capital system and allow city agencies to focus their scarce traffic calming resources on the places where people are dying — especially as COVID-19 continues to drain local tax revenues.

"Traffic violence doesn’t care about ward boundaries," added Jacque Knight. "The truth is, a lot of these streets are just overbuilt, because we thought St. Louis was going to be a city of a million people, and now it's 300,000. We hear, time and time again, that 'oh, we can’t fix these roads, because we don’t have the money.' But we’re never gonna have enough money. What we need to look at creative ways to right-size our streets."

Over-enforced and poorly reported

Those creative solutions, though, don't appear to be a part of the city's front-line strategy to end its pedestrian death crisis — and they don't seem to be on the radar of the journalists covering the surge, either.

In article after article and TV spot after spot, many of crash victims have been reduced to little more than their names and ages, and the universe of systemic factors that precipitated their deaths were left unexplored. Writers for the Post Dispatch took an appreciative tone in a recent article about a citywide plan to crack down on speeding and red-light running throughout the metro, including along several roads that were the site of pedestrian crashes — neglecting to mention the national dialogue about police brutality against BIPOC in street enforcement that St. Louis advocates helped launch following the shooting of Michael Brown by Office Darren Wilson.

Automated enforcement strategies like red light cameras fell out of favor in the city following a ruling on a 2011 lawsuit that heavily regulated their use, which means the latest push will almost certainly be handled armed officers — and some advocates fear that will mean more police violence for the city's people of color, even if it does succeed in curbing traffic violence. (St. Louis city officials did not respond to Streetsblog's request for comment.)

"It’s obviously going to criminalize more Black people in the city," said Xandi Barrett, a local sustainable transportation advocate."That’s definitely not how I think we should be dealing with this problem."

The Post Dispatch's failure to contextualize new enforcement efforts within the ongoing movement for Black lives wasn't the only thing that's troubled Barrett about local coverage of the recent deaths. She recently developed and distributed a toolkit for local journalists to improve their coverage of traffic violence, but says most local reporters didn't seem to get the memo.

"Most of them don’t even identify that these deaths are a trend," said Barrett. "They're treated as isolated incidents, and they don't talk about road design at all, except for maybe saying when the pedestrian wasn't in a crosswalk — but then, they don't say how far away the nearest crosswalk was. Really, a lot of these articles seem like they're adapted straight from the police report; unless you’re reading the newspaper every day, you wouldn't know [the scale of the problem]."

Until journalists, police, and local leaders start working together to holistically create a culture where traffic violence is not tolerated, advocates fear that pedestrians will continue to die.

"Whenever we talk about cars in St. Louis — and really, almost everywhere — we talk about ‘car accidents,’" adds Barrett. "That makes it seem like these crashes were unavoidable, just something that happened. We need to dig deeper and talk about what this really is: an epidemic."