Participants in a study who received cash for choosing modes of transport that are most beneficial to society ended up driving far less than study participants who did not get the reward — a finding that suggests that the U.S. might be able to reduce many car trips if existing auto-centric incentives were altered.

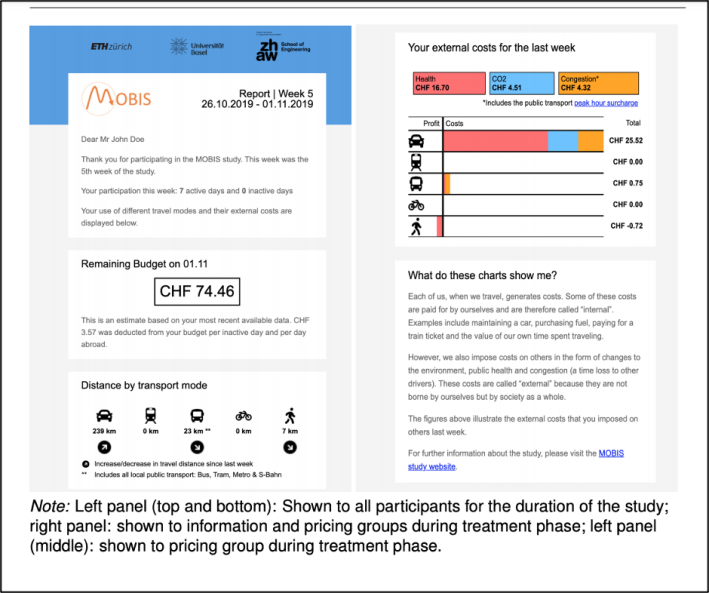

In the largest study of a comprehensive "polluter pays" pricing scheme ever conducted, a team of researchers invited 3,700 residents of Switzerland to download an app onto their cell phones that tracked their travel and then sent them a report that quantified exactly how much their choices cost their neighbors — in real money.

Researchers didn't just limit themselves to the most obvious costs that transportation imposes on society.

Unlike the U.S.'s fragmented mosaic of fuel taxes, roadway tolls, vehicle registration fees, and other piecemeal road funding sources — none of which even begin to cover the costs of maintaining America's streets, much less the broader social costs inherent to an auto-centric transportation approach — the app took into account virtually every social impact of participants' transportation choices, and translated them into francs and cents. Those included not just commonly taxed things like emissions, but also "noise and greenhouse gases, safety risks and health effects, lack of seats on public transport, congestion on the roads, [and] also the operating and maintenance costs for the transport infrastructure."

Put another way: the researchers essentially rolled together fuel taxes, congestion charges, vehicle miles traveled fees, and nearly every other conceivable road pricing approach into one simple and elegant app that anyone can understand at a glance.

To understand the true impact of the Pigovian pricing scheme, the researchers then divided the study into three key groups: one group whose members only received their report card on how deleterious (or beneficial) their transport behavior was to their neighbors, one which received the report card and a "budget" for how much societal damage they were "allowed" to inflict during the study period, and a control group with received neither. Members of group that received both were then told that if they underspent on their budget, they'd get to pocket the difference. (Notably, the budget was deliberately set at a generous level, so no participant would go into pollution "debt.")

The result? "Introducing a transport pricing scheme based on external costs that raises transport costs, on average, by 10 percent would lead to a reduction in the external costs of transport by 3.1 percent," the researchers wrote — meaning that when drivers are forced to pay something even a little bit closer to the real costs of their preferred mode, they find ways to drive less.

Drivers who only received their transportation report card without the financial incentive to get a better score, meanwhile, were unlikely to change their transportation behavior — just like the control group.

Of course, the Swiss experiment couldn't account for every externality of driving — and its results may not be strictly replicable in a car-crazy country like America.

For instance, the researchers didn't account for the additional societal costs imposed by drivers who choose dangerous, pedestrian-killing large vehicles instead of smaller ones — probably because Switzerland already imposes a large vehicle fee on the biggest passenger cars on the road. Nor did researchers account for the specific costs of excessive driver speeding, likely because the country already has some of the strictest speeding laws in Europe — and because those laws are backed up by safe, traffic-calming road designs, especially in urban areas.

Indeed, the impact of "polluter pays" pricing would almost certainly be different in dangerous, transit-poor U.S. communities, where most people have no choice but to rely on the highest-polluting modes. The U.S. has 51 percent more vehicles per capita than our Alpine counterparts, and Americans take nowhere near as many public transit trips as the Swiss, who average 70 journeys on the country's extensive rail network alone every year — more than any other European country.

Unsurprisingly, those travel patterns translate to big differences in the two countries' respective traffic violence stats; the U.S. has nearly five times as many roadway deaths per 100,000 residents than Switzerland.

Still, it's tantalizing to imagine what would happen if a comprehensive "polluter pays" principle were enacted on American roads, especially if proceeds from those fees were rapidly re-invested into safe, green options that would enable residents to make better transportation choices going forward. And until U.S. leaders figure out ways to clear the political hurdles that stand between them and making all commuters pay their fair share, motorists will probably keep driving America deeper and deeper into pollution debt.