Republican-leaning voters are more likely than Democrats to trade a walkable community for a large home, a new poll finds — but that result may say more about car culture's stranglehold on the American imagination than how either group really wants to live.

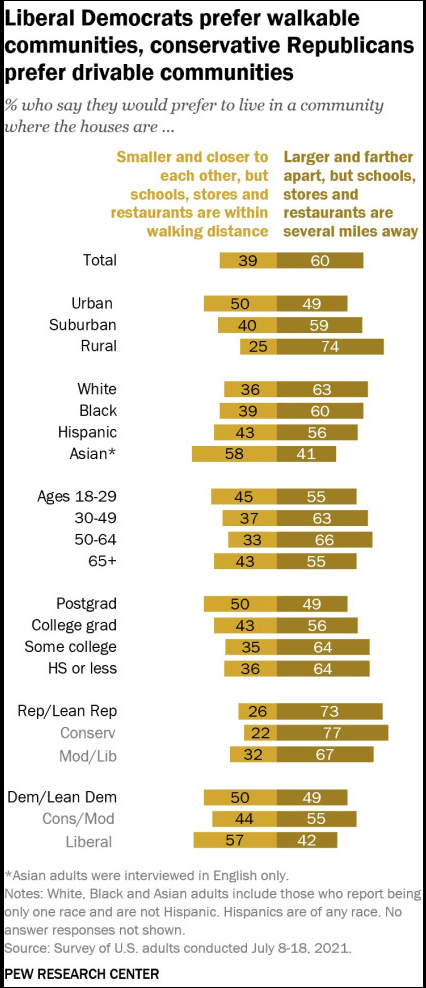

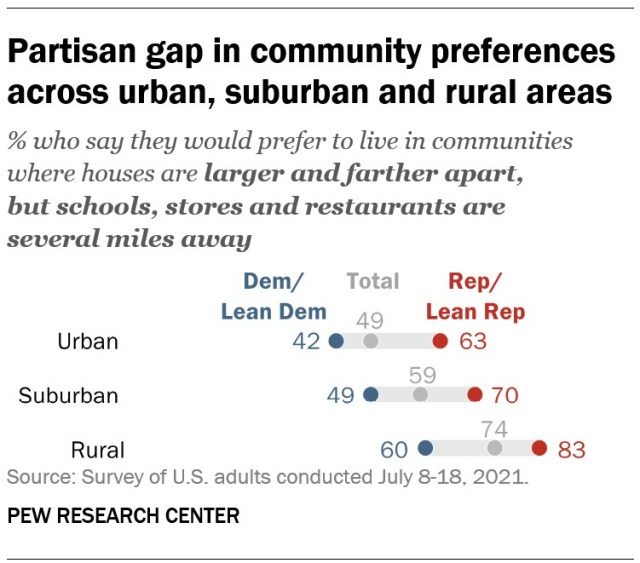

In a viral article for Vice News, journalist Aaron Gordon explored a recent Pew Research Center poll that found 73 percent of Republican-leaning voters would prefer to "live in a community where houses are larger and farther apart, but schools, stores and restaurants are several miles away." Only 49 percent of blue-leaning Americans shared that preference.

Gordon took the poll as evidence that walkable communities are "yet another dividing line in the American culture wars," and marveled at the fact that political affiliation was more predictive of respondents' preference for small homes in walkable neighborhoods than their race, age, or whether they live in an urban or rural area now.

But Pew's poll wasn't asking about how much various political groups prefer driving to walking, or even how much they value living within easy reach of the services they rely on most. Instead, it asked whether respondents would be willing to live in a small home within walking distance of schools, restaurants and shops — without specifying whether that walk would be safe, comfortable, or dignified.

In too many American communities, it's not — and it's been that way for so long that it's hard to imagine it any other way.

In the five short years since Pew first began asking respondents this frustratingly vague question as part of its 2014 polarization report, U.S. pedestrian deaths have skyrocketed a shocking 26 percent, in large part thanks the proliferation of unregulated mega-cars on roads that transportation leaders have often made no effort to calm.

Meanwhile, the average additional amount a U.S. homebuyer is willing pay for a house in a walkable neighborhood has remained flat since 2016 — but at a whopping $77,668, that premium still puts even basic walkability out of reach for most. (There's less data on renters' access to walkable neighborhoods, but considering the reams of research about the growth of poverty in both unwalkable suburban and rural areas, the outlook isn't good.) Some U.S. communities are pursuing zoning changes that would allow more Americans to enjoy a range of housing sizes within mixed-use neighborhoods — and neighborhoods built before the advent of the automobile tend to have a lot of those already — but the pace of change is still glacial relative to the demand.

Respondents to polls like Pew's literally can't afford to ignore those harsh realities when they make choices about where they live and how they get around — which could help explain why 60 percent of all Americans chose the "big house, lots of driving" option in Pew's survey, and why that number has increased from 49 percent in 2014.

In a country that has been deliberately manipulated by powerful interests into believing that the sacrifice of more than 36,000 people a year to traffic violence is the unavoidable price we must pay for American society, an auto-centric lifestyle isn't a preference. It's a survival strategy. And a big house on the side is just a bonus.

Seen through that lens, Pew's finding the 39 percent of Americans would still choose a small home in a walkable neighborhood is pretty remarkable — especially considering that America has nowhere near enough homes in safe neighborhoods to give the people what they want.

Interesting survey by @pewresearch. 1) The market isn't close to serving 39% demand for walkability. 2) Why is the choice house size v walking? I lived in a 4bd home in a rural walkable town as well as a 1bd apt in an unwalkable urban place. #falsechoicehttps://t.co/elskpvChP6

— Beth Osborne (@BethOsborneT4A) August 31, 2021

If it's fairly easy to understand why all Americans are devaluing dense neighborhoods as the roads and cars that run through them get deadlier, it's a little more challenging to understand why Republicans and other right-leaning voters are so much more likely to do so.

But anyone who's lived in a red community knows this: for many U.S. conservatives, owning a car carries a unique cultural weight that it simply doesn't in many blue circles.

To break the fourth wall for just a moment, I know something about red communities. I split much of my childhood between two counties in Michigan and Ohio that both went for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton by more than 20 points in 2016.

Because red America isn't a monolith, these two communities have little in common besides their voting patterns. One is an exurban bedroom community carved into Amish farmland with next to no sidewalks, and the other is a tiny, walkable town of 5,000 where 32 percent of the population lives below the federal poverty line. In Ohio, some of my dad's neighbors use their SUVs to haul horse trailers, while others drove Hummers to Starbucks on their way to downtown jobs (and a surprising number did both); in Michigan, my mom lives within spitting distance of a walkable Main Street that is home to the town hall, the grocery store, and many of the services she relies on, give or take the occasional Costco run across the state line to Indiana. My dad's town is 97 percent White; my mom's is just 66 percent.

In both cities, regardless of how residents actually live and what they can actually afford, cars endure as a powerful and enduring status symbol in a way that's difficult to explain to my neighbors in the blue city where I live now. Everyone wants one, most households have at least two, and almost without exception, those cars are huge.

You can, for example, think it’s dumb that people don’t want to get rid of their cars. But unless you reckon with what a car means to a Latino family in Mississippi or a Black man in Michigan for different reasons, your messaging will fail.

— Tressie McMillan Cottom (@tressiemcphd) August 5, 2021

The data bears this out nationally. Market research shows that when Republicans are asked what they want in a vehicle, they tend to throw out adjectives like “powerful," "rugged," and "prestigious” — three status-conscious modifiers that could just as easily be applied to the driver's desired image of himself. Self-identified Democrats, meanwhile, are more likely to pick more utilitarian modifiers like "economical" and "environmentally friendly," which may suggest that they think of their cars as tools, rather than extensions of their core identity.

Those attitudes can lead to staggeringly different choices at the dealership. Members of the GOP buy eight pick-up trucks for every one purchased by a Democrat, and they also buy roughly double the number of SUVs — and they replace those cars three to four times more often than their blue counterparts to make sure they're always in a fresh ride. For better or worse — well, mostly for worse — car ownership is seen by countless Americans as a marker of status and power and wealth, which is itself tied to the moralized concept of accumulated wealth as evidence of hard work, which 47 percent of Republicans and 29 percent of Democrats say they believe.

That's not to say that Democrats don't buy into the allure of car culture — they absolutely do — or that Republicans' willingness to give up walkability in favor of big houses and big cars is purely emotional. (And for the record: there's no clear correlation between states with the largest average home sizes and the largest percentage of GOP voters. Sprawl is, without a doubt, a bipartisan phenomenon.) Republicans are slightly overrepresented in industrial professions that encourage the purchase of big vehicles, and they're also more likely to support domestic automakers which are rapidly phasing out their smallest models in the name of higher profit margins.

But until we reckon with everything cars have come to signify in our culture — including the massive subcultures that glorify the automobile far beyond its mere transportation utility — more and more Americans will idealize car-centric lifestyles, and many will choose that life the moment they can afford it. Dismantling car culture starts with policy that makes other modes safe, attractive, dignified, and affordable — and yes, maybe even "prestigious" and "powerful," too.