The long-term health benefits of using bike share vastly outweigh the short-term risks, even in the most polluted and car-dominated U.S. cities, a new study finds — and cities who invest in reducing those risks by loosening car dominance can save even more lives and millions in precious public health dollars.

In what its authors believe to be the first study to quantify the public health benefits of U.S. bicycle sharing systems, epidemiological researchers at Colorado University calculated that on an average year, users of the mode saved the national healthcare system more than $36 million, despite the fact that there are only about 100,000 shared bikes in the country and many are located in dangerous, car-dependent cities. Riders themselves were saved a collective total of 737 "disability adjusted life years," or years spent living with debilitating health conditions such as cancer, dementia, and ischemic heart disease, thanks to the preventative power of active transportation.

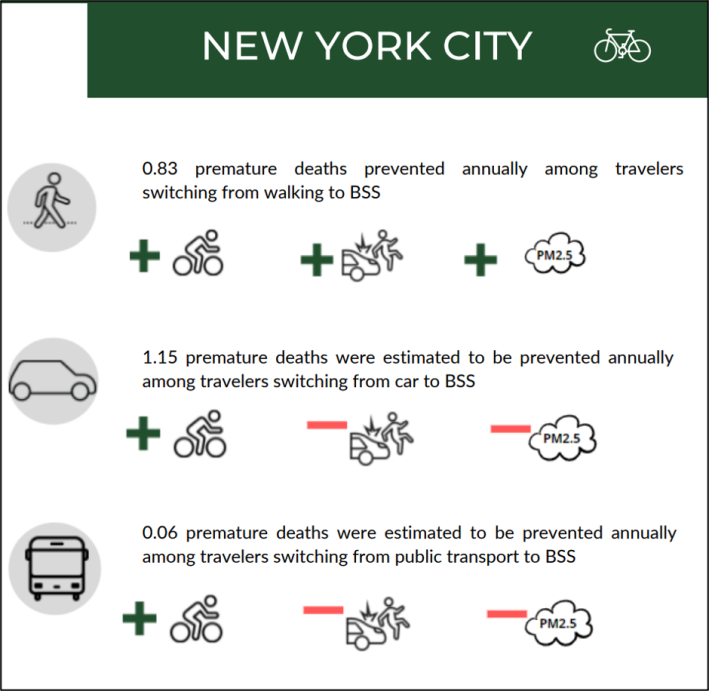

Perhaps the best case study of the public health benefits of bike share is New York City, whose robust Citi Bike program is home to almost a fifth of the shared two-wheeled vehicles on U.S. streets today. More than 40 percent of the savings accounted for by the study ($15 million) were thanks to the Big Apple alone, and the researchers estimated that putting 100,000 New Yorkers onto bike share would result in 15 fewer deaths, 2556 fewer disability adjusted life years, and more than $111 million fewer public health dollars spent annually.

"People don't necessarily think of transportation policy as a tool to improve public health," said David Rojas-Rueda, an assistant professor of epidemiology and a co-author of the study. "And there are people out there who question whether bike share is a good investment at all, just because there’s so much pollution on our streets and so much danger from traffic fatalities. So we decided to quantify it."

Of course, the life-saving potential of bike share is limited by the deadly reality of car dominance.

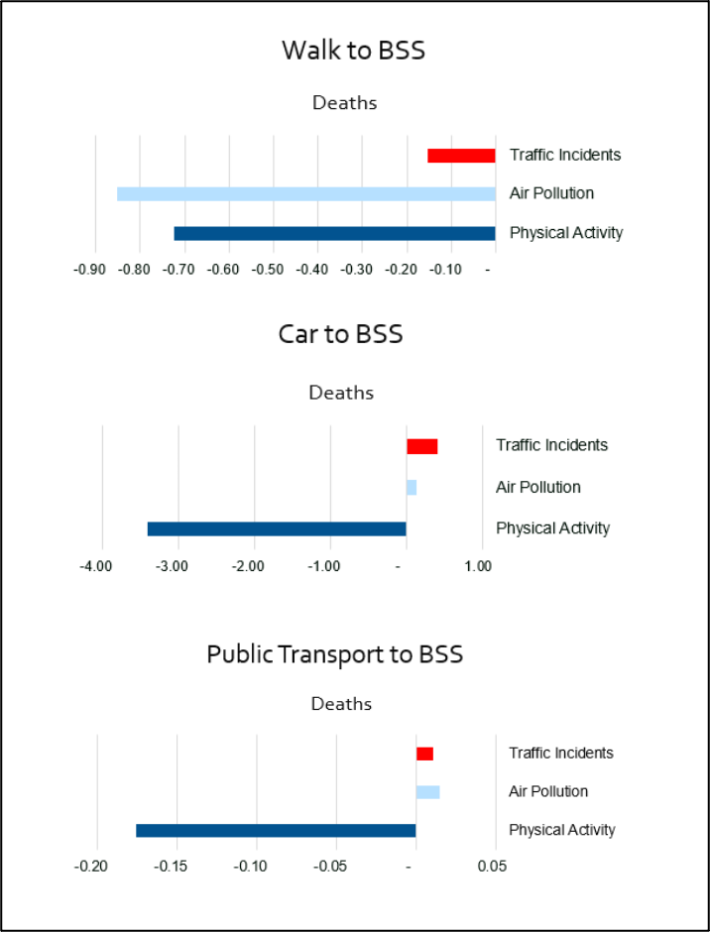

The researchers found bike share users had a marginally higher risk of dying in traffic crashes or from pollution-related ailments compared to drivers or transit riders, although they also had a much lower risk of dying from diseases related to physical inactivity than their inactive counterparts. (Pedestrians, meanwhile, had a higher risk of dying from all three causes compared to their counterparts who biked.)

In real numbers, those risks aren't as big as you might think: famously, zero American residents died on bike share vehicles from 2007 through 2014, and deaths on the mode are still rare, a fact that experts attribute to many cities' efforts to plan bike share networks in tandem with bike infrastructure improvements.

Still, Rojas-Rueda emphasized the remaining risks of bike share can be mitigated through good Vision Zero planning. But the public health risks associated with sedentary modes such as driving are baked in.

"The more [bike share] users we attract, and the more we improve the street environment, the more we increase the public health benefits," he adds. "And if you increase the risks [to cyclists,] of course, the public health benefits [of cycling] will reduce."

Even less bikeable U.S. communities are experiencing the public health benefits of bike share — which they could easily amplify by investing in the mode while investing in safer streets for riders.

"I think the message to cities is that bike share — and biking in general, though that's harder to quantify in the way we do in this study — can contribute a lot to their long term goals," said Rojas-Rueda. "Most cities want to improve quality of life, the economy, the climate, and their public health outcomes. Bike share does all those things."