It’s the data, dummy!

The simplest way to convince the public to move forward with policies that best serve the underserved is to give the raw numbers that back up great ideas, a top urban planer told advocates during a recent summit on equitable planning.

During the Streetsblog-sponsored Unurbanist Assembly last week, Anika Goss, the chief executive officer of Detroit Future City, stressed that the first step in changing things for the better is determining exactly what you want done — then finding the data to prove your point.

“It all starts with the story: What are you trying to change,” said Goss, who for the last five years has been using research and data to help transform Motown into an equitable and sustainable city of the future. “Then you get the data that backs it up.”

Once the data that actually proves the point you want to make is at hand, Goss recommended using a “data walk” — a way to explain in simple terms what the data means so everyone can easily understand it — to convince the public and government officials to get to work on preferred projects.

Goss said she learned how to use a data walk the hard way.

“At first, I thought it wouldn’t work because it was too pedestrian,” she said. “But it did work. People across all education levels got into it. They understood and were able to make choices. It makes a big difference to the community.”

But the data you need isn’t always easy to come by, and it sometimes requires a bunch of research to find — as Goss found out during a study of one of the most under-studied demographic groups in Tiger Town.

“There was no data on the middle class African-American residents of Detroit,” she said. “And if the data isn’t there, you have to find it.”

That meant a labor- and time-intensive journey to compile data on the illusive group — but Goss said it was worth it in the end.

“At first, the data was three pages long,” she said. “Now, we’re getting ready to launch a whole data platform.”

That platform has now grown to include cities beyond Detroit, too and sheds a light on a community that has lacked proper study for years.

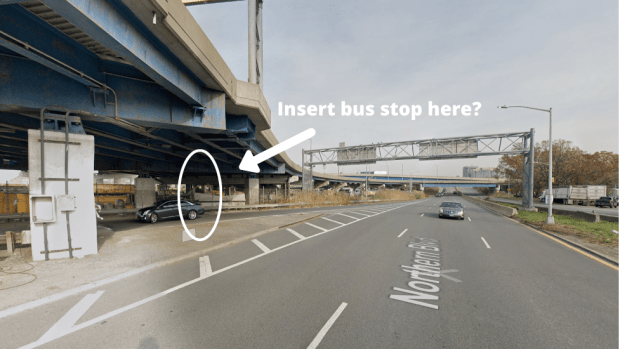

Such efforts to use data to uncover the story of forgotten communities can undoubtedly make cities more equitable — but it doesn't always work out that way. In a question period with viewers from around the world, one attendee worried that some of the data in her community isn’t reliable, citing a problem she came across after moving to Cambridge, Mass. near what she thought was a bus stop that would help her get quickly to work.

It turned out the bus stop had been discontinued some time before, and despite still being listed on bus maps, it was only being used as a loading zone.

When she questioned why the defunct bus stop was still appearing on local routes, the transit authority told her it remained there in case officials decided to put the stop back into service back some day. But in a cruel Catch-22, the same official noted that local ridership data would probably indicate that there's no need to bring the stop back, because — wait for it — no one is using it now.

“But how can anyone use the stop when the bus doesn’t stop there?” she said. “It’s like the urban planners are playing Simm City — like it's a video game that is not affecting peoples lives."

The Unurbanist Assembly was a 23-hour virtual community streaming live from Savannah dedicated to confronting the legacy of racism in urban planning. Learn more about it here.