Around the world, cities that do the best job of catering to the needs of women cyclists also have the highest level of cycling overall, a new study finds — and the U.S. has among the lowest share of female-identified riders on the planet.

In a comprehensive analysis of travel surveys from 11 countries across the globe, a team of international researchers found that the United States ranked second-to-last for both cycling mode share overall, and for cycling mode share specifically among women-identified riders. Americans of all genders travel by bike for just 1.1 percent of trips, and American women choose the two-wheeled option for just 0.6 percent of theirs — numbers that pale in comparison to top-ranking country the Netherlands, where women take 28.2 percent of their trips by bike.

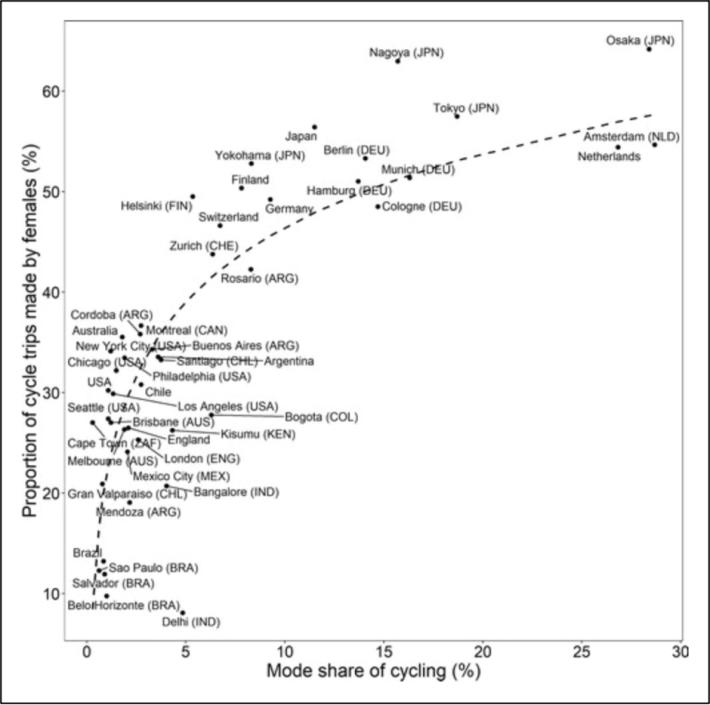

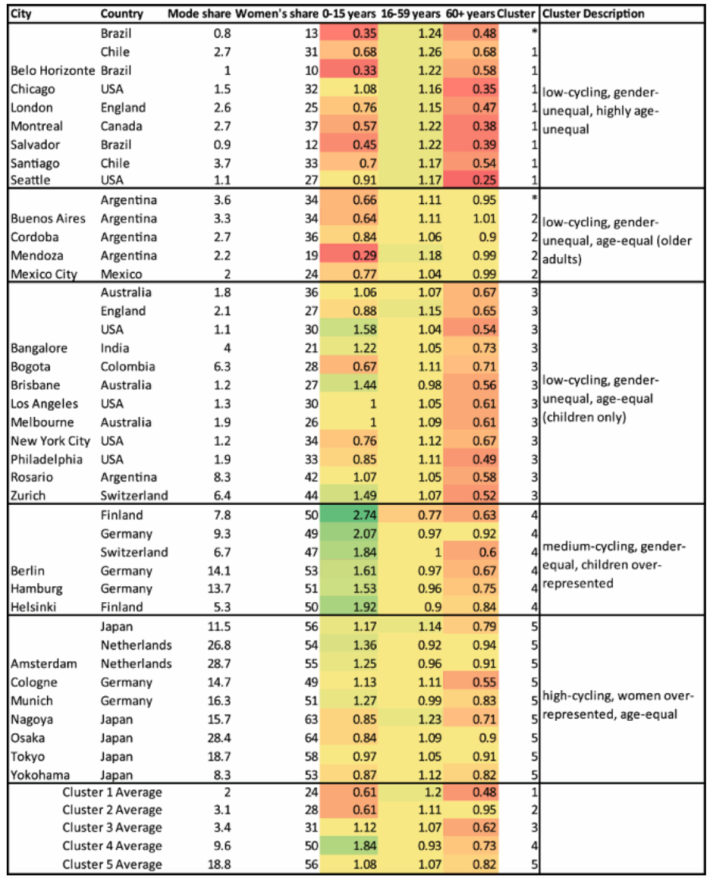

But the Dutch aren’t the only ones whose success at getting women in the saddle is correlated with high cycling rates overall. The researchers noted “a strong positive association between the level of cycling and women’s representation among cyclists,” adding that “in almost all geographies with cycling mode share greater than 7 percent [of all trips,] women made as many cycle trips as men, and sometimes even greater.”

Put another way: when communities make transportation choices that successfully encourage women to ride, everyone comes out to join them. And when they don’t, most folks stick to driving.

That may be a surprising finding to those who think of “bicycle advocacy” as a gender-neutral term that’s largely synonymous with “protecting people on bikes from traffic violence.”

But throughout the report, the researchers referenced the many ways that women’s unique transportation needs shape their experience on two wheels — and not just their need for safety from drivers. Women are not only less likely to ride on dangerous roads with little protected infrastructure than their male counterparts, but that they take shorter trips by bike and travel more often for reasons unrelated to a traditional work commute, like running household errands.

That may be because women tend to do a disproportionate share of household labor, which makes them more likely to “trip-chain” regardless of how they get around. A caregiver, for instance, who has to not only make it to work, but to pick up the kids from school, run to the grocery store, and check on an elderly relative all in a single trip will have fundamentally different needs of her local transportation network than someone whose only regular household responsibility is making it to the office and back.

(The authors did not explore the travel needs of gender nonbinary people, who are typically not included in city and national travel surveys, which is a problem.)

That might help explain why three cities in Japan — Osaka, Nagoya, and Tokyo — had the highest proportion of cycle trips made by women, despite the fact that the country has vanishingly little protected bike infrastructure besides sidewalks shared with pedestrians, and nearly three times the rate of fatal crashes per 100,000 kilometers biked than the Netherlands. (Of course, they still have have about half the fatality rate as the U.S.) Some advocates have speculated that’s because an estimated 70 percent of Japanese women leave the workforce after they have their first child, often taking on the larger share of the household labor — and thanks to Japan’s compact "15-minute city"-style community design, those duties, which have become unusually gendered in the country, are also unusually convenient to complete by bike.

Presumably, Japan’s share of women cyclists could be even higher if the country also had protected bike lanes — something for which many cyclists in the country have long advocated.

Interestingly, the researchers didn’t find a similar association between high cycling levels overall and high cycling levels among all age groups. Several of the cities the researchers examined had relatively few people on bikes, but a lot of children scooting around on training wheels — something they noted “can be a barrier to its consideration as a mainstream transport mode” if the bicycle comes to be too heavily regarded as nothing more than a child’s plaything.

Of course, most U.S. cities don’t have to worry about bikes becoming over-identified with little kids — because parents won’t dare let their children ride on our dangerous roads. Of the four American cities that the researchers ranked — Los Angeles, Philadelphia, New York, and Seattle — none had a greater than 0.76 percent cycling mode share for riders under 15 years old, or less than a third of the proportion of bike trips taken by Finnish children, who rode the most often.

Meanwhile, the U.S. city with the highest share of women riders, New York City, still had a 66-percent male ridership. There are are nearly 400,000 more women than men in the Big Apple.

The researchers behind the paper were careful to note that their data didn’t speak to all the reasons why people of various identity groups might ride (or not ride) on city streets. A truly intersectional study, they said, would analyze how “disability, ethnicity, income levels” and other factors impact the lived experience of people on bikes — something that’s hard to analyze at a global scale, because communities around the world so rarely collect much cycling data at all, much less good data that provides a detailed picture of who rides and why.

But the study may validate the old truism that the presence of diverse women on bikes is the single best indicator of a healthy cycling ecosystem — and that it’s past time that U.S. communities start centering the unique needs of marginalized people when they make our transportation decisions.