As President Biden pushes to install a network of electric vehicle chargers across America, some advocates are wondering where they will all go — and if the effort will deal a blow to the movement to reform urban parking policy.

Some sustainability advocates applauded Biden last month when his long-awaited infrastructure plan, the American Jobs Act, included a program that would fund the construction of 500,000 new EV chargers. But besides a commitment to building a nationwide network of fast chargers on highways, Biden hasn't yet clarified how, exactly, that money would be divided among incentive programs to put chargers in the homes of private drivers, the parking lots of private businesses and apartment buildings, and even city-subsidized spots on public streets — and what the consequences of those choices will be for cities.

Those details matter deeply to advocates who have been fighting to minimize the amount of land devoted to private vehicle storage, with some advocates fearing that the EV revolution could justify a surge in mandatory parking minimums they’ve long sought to abolish.

“It’s under-appreciated for sure that EV charging policy is parking policy,” said Tony Jordan, president of the Parking Reform Network. “At the end of the day, Biden’s plan is really just giving people money to upgrade their parking. Hopefully it won’t be used to build new parking, but we don’t know that for sure yet.”

When parking spots become fueling stations

Long before electric vehicle adoption became a major policy focus in Washington, parking reformers like Jordan have been highlighting the deleterious effects of saturating American cities in asphalt and letting drivers store their vehicles there for free or below-market prices. In addition to reinforcing car dependency by making driving more convenient than more sustainable modes, bad parking policy gobbles up scarce urban land that could be devoted to better uses like affordable housing or providing other essential services.

And building and maintaining those spots doesn’t come cheap; one study found that the average American renter with garage parking pays 17 percent more in rent than renters in apartments without parking (though the market value of a parking spot in an urban area is likely far more than what developers charge for it, thanks to baked-in city subsidies).

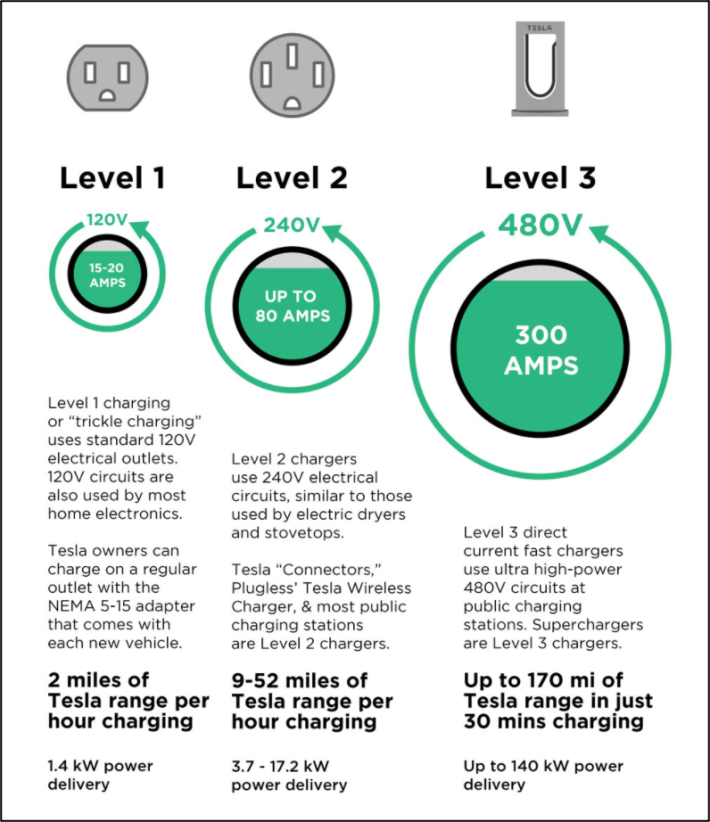

But in the age of the electric vehicle, many of those expensive parking spaces will have to do double-duty as fueling stations — and unless current technology rapidly evolves, that fueling process won’t always be quick:

The Level I “trickle” chargers that are included with most electric vehicle purchases — they are plugged into a standard wall socket — take 10 hours to give a Telsa a mere 20-mile range, or a whopping four days to get up to full power. At the opposite end of the spectrum are Level III chargers, which cost an estimated $10,000. These “rapid” chargers can juice up a vehicle in as little as 30 minutes, but because they use as much electricity as a modest-sized home uses in an entire day, they actually cost around $50,000 to install in addition to the massive energy costs of charging itself, putting them out of reach of many home and business owners.

Most experts expect that because Level III chargers are so spendy, most of the EV infrastructure built under Biden’s program will be medium-speed Level II chargers, with a smaller number of rapid chargers stationed along interstate highways to decrease range anxiety among long-distance travelers.

Today, Level II chargers — which cost about $2,000 to $3,000, and can take three to six hours to reach full battery capacity — are most commonly found in commercial lots, like the ocean of asphalt surrounding the average American mall, thanks to hefty federal tax credits to the business owners who can afford to install them and retrofit their electrical systems to handle the increased energy demand. Incentivizing shoppers to linger for hours at centralized, big-box retail establishments while they fuel up at a state-subsidized charger is certainly efficient, but it isn’t exactly fair to small business owners in walkable, parking-light neighborhoods that actually do the most to support local economies and civic life.

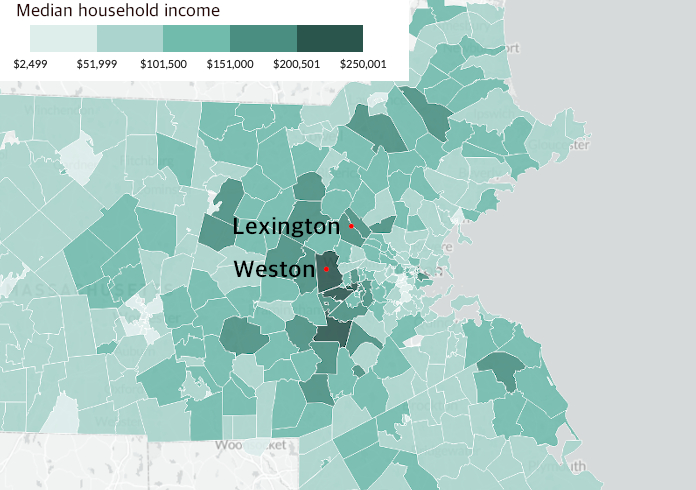

Given that commercial developers already have access to federal dollars for chargers, Biden’s program may well focus on maximizing charging capacity in residential neighborhoods, where 80 percent of vehicle charging actually happens, often while drivers sleep. But if the bulk of the American Jobs Plan dollars go to private homeowners, it will essentially amount to a massive handout to wealthier landowners — the same group some advocates argue already benefit unfairly from consumer rebates on EVs themselves. (Both Streetsblog MASS and Streetsblog NYC have explored the current inequity in e-car subsidies.)

On the other hand, giving renters access to chargers at multi-family apartment buildings isn’t exactly an equitable outcome, either — because renters who make use of them will then be saddled with the high costs of car ownership, in addition to a likely rent hike to pay for the ongoing maintenance of their new electric amenity.

“The tricky thing about putting EV chargers near multi-family homes is that renters are less likely to own a vehicle at all, and they’re far less likely to purchase an EV in the near future,” said Billy Grayson, director of the Urban Land Institute’s Center for Sustainability and Economic Performance. “But at the same time, if we want people to trade in their gas-powered vehicles — and certainly we do — chargers should go where a lot of people live, where a lot of people work, and then where people shop and visit, in that order.”

Can an EV charging program ever be equitable?

Despite their reservations, both Grayson and Jordan think that America can make EV chargers ubiquitous enough to get drivers to ditch fossil fuels, without further paving over cities and towns in the process. But doing it will require thinking strategically — and a little outside the box.

“We should be looking to take already-existing parking that can’t easily be retrofitted – think underground garages, or segments of streets that aren’t likely to become bus lanes – and concentrate our efforts there,” said Jordan. “Open up private lots to the public, especially in neighborhoods where people can’t access [electric vehicle charging] otherwise. Solar-charge as many stations as you can, sell the excess power back to the grid, and direct that money to low-income communities. Don’t put those credits into suburban garages where people can afford to install their own ... and of course, I would hate to see this money go towards building any new parking, because we already have so much.”

Some forward-thinking developers are taking things a step further. Instead of giving their residents access to a garage full of personal parking spaces outfitted with individual chargers, the developers behind some luxury apartment buildings are allowing customers to reserve time in a single, shared Tesla for free. Grayson says schemes like this may become even more critical when the rise of the AV collides with the rise of the EV.

“In 10 to 30 years, we’re going to be completely redesigning our infrastructure again for autonomous vehicles, and they will have very different opportunities for equity — and opportunities that run counter to equity,” Grayson said. “It would be really dumb if electric cars weren’t eventually shared; these cars really should really be on the road every minute they’re not charging.”

But even then, trips in private EVs should, ideally, be rare — and trips on high-quality electric buses, trains and other high-capacity shared modes should be the norm.

“From a climate perspective, the best car is no car at all,” Grayson said. “Creating walkable, bikeable, transit-rich neighborhoods should still be our number one priority, and for every dollar we invest into EV charging, we should be investing at least $1.50 into those modes. But in those cases where we’ve made the decision that it’s still important to provide car infrastructure, then yes — we should make sure those cars are electric.”