"Cruise control" technology was invented to help drivers maintain a safe and steady speed — but more often, they use it to go faster than they would without it, a new study finds.

In a recent study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety that could have troubling implications for the next steps in the automated vehicle revolution, researchers studied drivers' use of adaptive cruise control, a fancy version of the familiar speed-regulating technology that comes standard on most America cars today. In addition to keeping a car moving at a fixed rate of speed, adaptive cruise has the ability to automatically slow down a driver when she begins to creep up on another vehicle, maintain a safe following distance at a lower speed, and then accelerate back to the pre-selected "cruising" speed once the way is clear.

The technology has occasionally been hailed as a possible solution to the epidemic of speeding on U.S. roads (or at least a way for drivers to cut down on pricy speeding tickets). But the researchers found that the drivers who use it are actually 24 percent more likely to break local speed limits than when they drive without advanced assistance. (Though it must be noted that the drivers in the study without adaptive cruise control still sped a depressing 77 percent of the time.)

Drivers with ACC-equipped cars averaged a stunning eight miles per hour over the limit when roads were signed for 55, though they did hit the brakes a little in areas with 60- or 65-mile-per-hour limits, where they drove about five miles per hour faster than they were legally allowed.

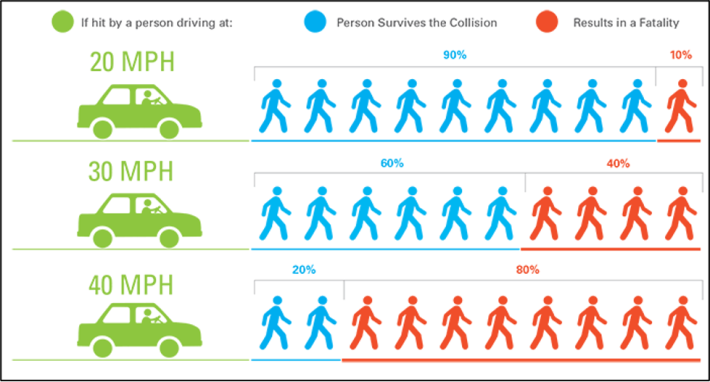

On average across all these scenarios, researchers estimate that the speeding behaviors of ACC-equipped drivers put them at a 10-percent higher risk of dying in a crash than drivers who don't speed.

And they're certainly more likely to kill other people — especially if those other people aren't inside a car themselves. Pedestrians hit by drivers traveling at speeds over 58 miles per hour or more die at least 90 percent of the time, and no advanced cruise control system is currently configured to maintain a safe distance from a walker 100 percent of the time, because scientists still have not fully cracked the problem of how to keep a robocar from running someone over.

The reports adds to the growing mountain of evidence about the dangers of many forms of partial automation U.S. roadways — especially when there's no mechanism for preventing drivers from using safety tech to more easily do dangerous things behind the wheel.

"Automation, like any system, can be used properly or misused," said Sam Monfort, a statistician for the Institute and the lead author on the study. "We know a lot of drivers are using cruise control, and as we add things like lane centering, that cruise control is getting more advanced — especially as we keep marching towards fully-automated car travel. We need to pay attention to how that influences the way they drive."

But as that relentless march continues, the question of which advanced driver safety features are actually making our roads safer today keeps getting murkier. Monfort notes that combining adaptive cruise control with intelligent speed-limiting technology — as will be required on all new European cars by 2022 — might seem like a good idea at first, but it could backfire if the move incentivizes drivers to just turn the tech off and hit the gas.

"If you implement a speed limiter, will the riskiest drivers just get frustrated and revert back to manual control — and ironically, increase their risk to others?" Monfort asks. "It's a possibility."

That question is a topic of hot debate in the trucking industry right now, as Congress mulls whether to resurrect an Obama-era bill that would have required speed limiters and adaptive cruise control on all large commercial vehicles. (IIHS has publicly supported it.) The Truckload Carriers Association is pushing for the legislation, which would cap all semi truck speedometers at 65 miles per hour and give rigs advanced cruise control, essentially calling bull on other industry groups who claim that truckers will be put in danger if they can't theoretically outrun a drag-racing driver.

Of course, the techno-optimist answer to this conundrum is pretty simple: install speed limiters and adaptive cruise control on all cars and trucks, and then equip those vehicles with "geofencing" technology that prevents a car from traveling faster than the posted speed limit without an override option. (Of course, Vision Zero leaders Sweden and Norway are already testing this idea.)

But until that fantasy is somehow made politically and logistically feasible — or until we ever manage to actually invent an autonomous car that doesn't mow down walkers — we'd be wise not to assume that partial automation tech like adaptive cruise control is necessarily making our roads safer.

Or, as Monfort succinctly puts it: "If AVs are going to continue to speed like the drivers of today’s vehicles do, they’re not going to live up to their safety promises."