If city and regional leaders were writing next federal infrastructure bill, mass transit would be a top priority and highways would be de-emphasized, a new study suggests.

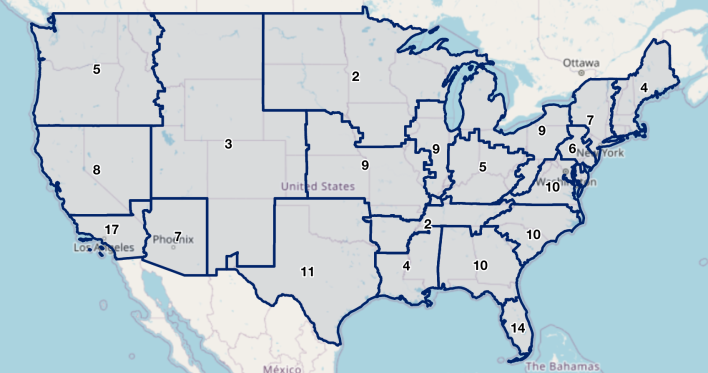

As part of a survey spanning 100 metropolitan areas and 139 cities across the country (later translated to into a nifty interactive map), researchers at The Kinder Institute for Urban Research asked local and regional leaders to identify their top-five infrastructure priorities, and to flag those that gained urgency during the COVID-19 pandemic. Not surprisingly, transportation rated as a top concern for municipalities, with 37 percent of all high-priority projects directly related to mobility — more than any other kind of infrastructure.

But the researchers were surprised to find that mass-transit projects were an especially high concern, even in regions not known for bus and train travel. An impressive 159 transit projects made the survey respondents' wish lists, or 21 percent of the transportation projects they marked as high-priority; only 90 highway projects, by contrast, were named among local leaders' wish lists.

"It's surprising," said William Fulton, co-author of the study and himself a former mayor of Ventura, Calif. "The pandemic really has changed people's attitudes toward what critical infrastructure is. Public transit is more essential than ever, because the essential workers we all rely on disproportionately use it. At the same time that [public transit agencies] lost ridership, they also became more important than ever for our economy to function."

Fulton was careful to note that the survey respondents were not always able to offer an estimate of how much their transportation projects would cost, so it's hard to know what share of spending would go to highways, as opposed to transit, if local leaders were in charge. But the survey does suggest that local transportation priorities may be out of sync with traditional federal funding ratios, which devote about half of federal dollars and 80 percent of gas-tax revenues to highways, regardless of what American communities need.

"The way federal infrastructure policy works, it's basically driven from inside the beltway by politically influential constituencies working from the top down," Fulton said. "At the local level, you know what you need, but you have to plug in the gaps with other funding sources and just do the best you can. We thought it was important for [state and national politicians] to get a feel for what most folks at the local and regional level think should be our infrastructure priorities, rather than just assuming that the usual top-down process will be sufficient. Because often, it's not."

Transit projects aren't the only kind of green infrastructure that local leaders are clamoring to build with little federal support. Leaders across the country identified 43 different bicycle and pedestrian initiatives as top priorities, despite the fact such improvements are traditionally (under)funded by states and localities; less than two percent of federal dollars goes to the Transportation Alternatives program, the largest pot of federal money for active modes.

Surprisingly, another 105 projects related to parks made the list, despite the fact that city green spaces aren't always a major topic in conversations about federal infrastructure funding. Fulton says that speaks to the effect of the pandemic, which highlighted the crucial importance of public recreational facilities, as well as the need to de-silo efforts to create great parks – which contain some of our most important car-free pathways — from broader efforts to create great places to walk and roll on city streets.

That's just one example of the kind of intersectional thinking that the study suggests will be key to crafting a national infrastructure package that meets municipal needs.

"The power of infrastructure investment is multiplied by desiloing," Fulton added. "Especially when we talk about using infrastructure investment to fight climate change...The Biden admin would do well to listen to local leaders on how all these things work together at the local level."

When it comes to transportation, Fulton says erstwhile-Mayor, now-DOT head Pete Buttigieg may understand the importance of listening to municipal leaders "better than just about any secretary of transportation we've ever had." But whether he'll be able to sway legislators in the House and Senate, both of which are structurally designed to over-represent the concerns of voters in less transit-dependent regions, remains an open question.