Drivers aren't just killing cyclists on quarantine-emptied roads — they're also leaving them to die there.

As part of its 2020 Cycling Deaths project, journalists at Outside Magazine analyzed media reports about 697 fatal cycling crashes and found that more than a quarter (26.3 percent) of drivers who killed a cyclist last year fled the scene of the crime. The official federal statistics about hit-and-run rates won't be released for approximately two years, but the magazine noted that the data, which was analyzed with the assistance of information scientists at BikeMaps.org, is likely a strong representative sample of a death toll whose "total is likely significantly higher."

If that's true, 2020 may be among the worst years on record when it comes to dangerous drivers leaving their victims to die.

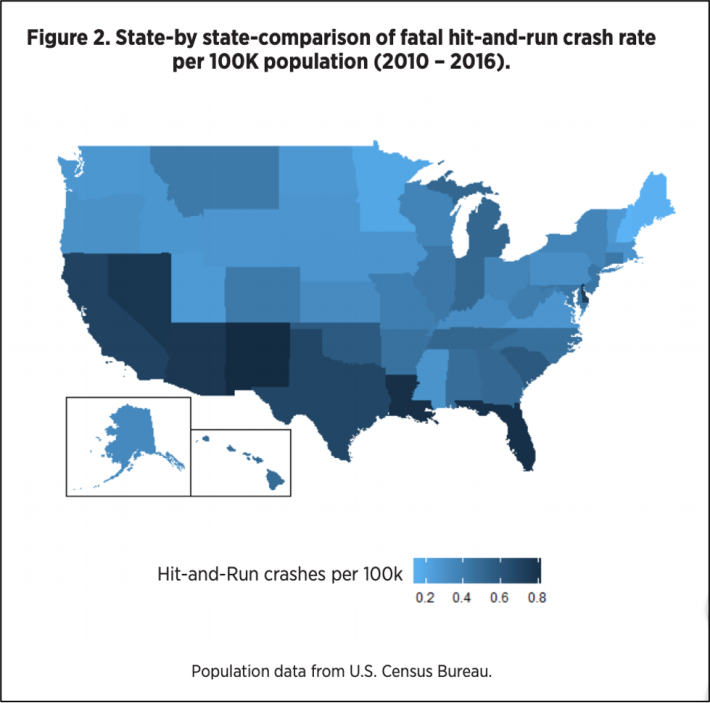

In 2018, researchers at AAA sounded the alarm that hit-and-runs against vulnerable road users had hit the highest point in recorded history, climbing 25 percent in just four years. At the peak of the surge in 2016, one in five dead pedestrians was abandoned in the road by his or her killer before help could be called. About the same proportion of cyclists who would later succumb to their injuries were abandoned by the drivers who struck them that year, too — but 2020 was even worse. (Hit-and-run fatality rates for drivers struck by other drivers, meanwhile, never exceeded more than one percent over the course of the study period.)

"I wasn’t surprised by this data," said Tiffanie Stanfield, founder of the non-profit Fighting Hit and Run Driving. "The pandemic provided drivers with a license to speed, and heightened the population of cyclists and pedestrians on the road. That balance is still off — but we haven’t done things like increase the enforcement to address the change."

Despite its rising prevalence in our roadway death totals, hit-and-run driving has been a relatively under-studied facet of our national traffic violence epidemic. But some experts believe that with the right mix of solutions, we can prevent dangerous drivers from fleeing accountability — even during a quarantine order, when bystanders are less likely to witness their crimes.

Outside Magazine rightly emphasized the importance of reducing the number of "hits" in our hit-and-run driving epidemic — or at least making those crashes less likely to be fatal — by calling for common-sense solutions like protected bike lanes, better new car safety standards, improved education for drivers, and increasing cycling rates to encourage safety in numbers (as this research showed). But other researchers have said it's necessary to tackle the far trickier "run" side of the equation — and emphasized that we need to look beyond enforcement alone to keep drivers from fleeing.

In its review of the academic literature on hit-and-runs, the AAA researchers found multiple studies that suggest that increasing legal sanctions for scofflaw drivers actually did not consistently decrease the prevalence of the crime — and in some cases, it even made the problem worse, because drivers' fears of particularly harsh punishments for traffic violence actually gave them an added incentive to flee.

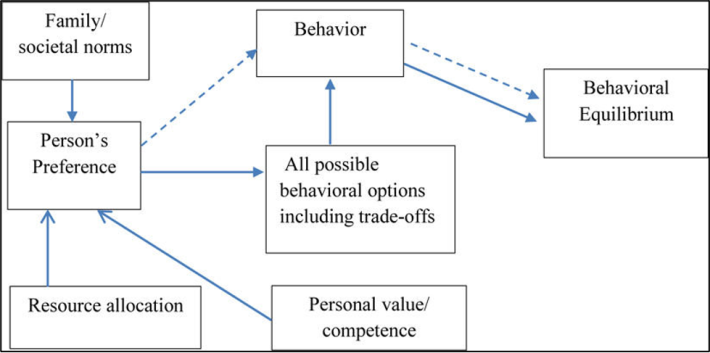

To get to the root of why drivers run, and how they might be stopped, researchers at AAA considered two common frameworks for understanding why people commit such devastating crimes.

The first, known as the Personality Theory, posits that some hit-and-run drivers simply have "underlying personality characteristics that predispose [them] to fleeing the scene of a crash" — which underscores the importance of good transit, walking and biking options keep evil jerks from climbing behind the wheel.

But another framework, known as the Rational Decision Theory, posits that some drivers flee for a range of interconnected reasons that must be addressed with comprehensive policy — namely, "that they have the opportunity, the incentive and the ability to flee." A drunk driver, for instance, might abandon a cyclist he's just injured because built environment factors give him an easy opportunity to get away without anyone seeing him, such as a lack of street lighting on a dark night, or bad zoning practices that make a road an unattractive place for potential witnesses to linger.

But if the driver is a person of color, he also might be running because he justifiably fears the possibility of police or carceral violence if he does call for help, which gives him a heavy incentive to flee — and if he's driving a car that was all but designed to kill a cyclist without leaving a scratch, he also has the ability to get away without attracting attention.

Under this framework, preventing a driver from fleeing the scene might take a full-court press: not just penalties for the driver who committed the crime, but also, possibly, adding streetlights, and reforming land use to encourage human activity on the road, and removing police from traffic enforcement, and mandating crumpling bumpers on all new cars.

There's even some evidence that even unexpected reforms could reduce the incidence of hit-and-run. A California study found that drivers fled less often "after a law was put into place allowing undocumented immigrants to receive driver’s licenses," even though the rates of overall collisions remained the same.

But as the pandemic continues to suppress vehicle traffic, advocates say we can't wait to make the lowest-lift reforms, like educating drivers on the importance of getting help for crash victims — because if we don't, more people will die.

"More than anything, we need awareness, exposure, and education," said Stanfield. "Remember the basics: Call 911, stay on the scene. It all comes back to that."