Editor's note This article was written in response to an article on Streetsblog USA about a proposal to create an active transportation administration or czar at the U.S. Department of Transportation. We're pleased to publish multiple perspectives on this important issue.

A shift in messaging about how America gets from one place to another is emerging. At his confirmation hearing, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg pointedly called out the auto-centrism and inequities of our transportation system and noted the economic success cities like his own South Bend have had by making transportation options like biking and walking safer and easier to access. Could we possibly be on the verge of a transportation system that actively serves all Americans, whether they drive or not? Is it finally time to provide real mobility to those that have been denied and harmed by policies of the past? Could transportation infrastructure actually become part of the solution to climate change instead of a liability?

Now more than ever it feels like achieving these goals is possible. To be successful, we need to focus our efforts on real, meaningful policy change and ensuring that resources follow those changes to truly transform the system, rather than just rehashing what we spend on auto-centric programs that don’t work.

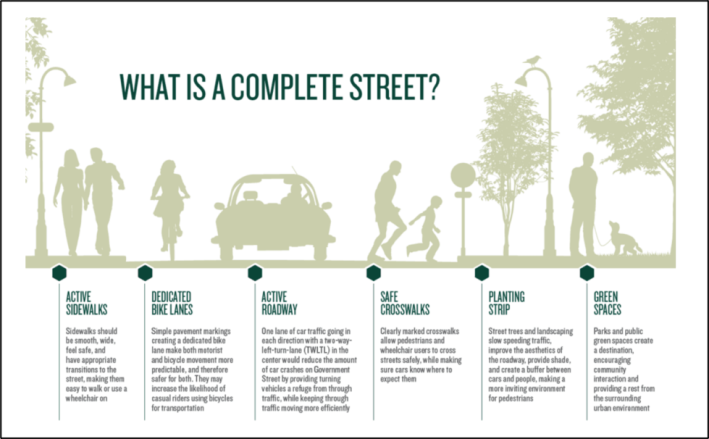

Real change is a Complete Streets approach to our transportation system — ensuring that every road, bridge, transit stop, and trail built across this country is built with all people in mind: people biking, people walking, people using wheelchairs or other mobility devices, transit users, and drivers. Real change is measuring the success of our investments based on whether people have access to jobs and essential services whether they drive or not. As the Biden administration focuses on building back better, we must push for tangible change that improves the lives of people most directly harmed by past injustices and made vulnerable by funding and policy decisions in designing the built environment: Black and brown communities and low-income communities whose needs have usually been an afterthought to our road system.

Our organizations believe that putting advocacy efforts behind creating new agencies or interagency committees would be a cosmetic change no more meaningful than a bike sharrow painted on a four-lane 45mph road. At worst, it would take energy away from real change by creating a positive talking point when we should be creating a transformational approach to transportation. The urgency of the crises before us require more from us than “checking a box” and potentially undermining the very change we are seeking.

What does it look like to write a positive talking point without acting on real change? As one example: over the past 15 years, in an effort to make transportation research more forward-looking and multimodal, USDOT created a research agency (called the Research and Innovative Technology Administration), then later moved it to the Secretary’s office under a new Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology. Now, some are talking about the need to move it back to its own agency. That’s 15 years of effort in reorganizing and reshuffling without ever fixing the problem the agency was created to address. We can’t repeat this approach.

Today there are calls for a separate administration within DOT for active transportation or for overall mobility. But these efforts do not address the problem: the fact that our roadways are designed and operated for one type of user (drivers) to the detriment of all other users (new mobility, transit riders, and those walking, biking, or rolling). With a new administration, “other” users would continue to be a side-project or retrofit to roads, rather than acknowledged as integral to who our road network should benefit. A separate administration furthers the notion that non-drivers are superfluous and something separate from the roadway user, allowing other organizations to turn advocates away with: “That’s not my department.”

Say, hypothetically, a new active transportation office in DOT had ten times the $500 million each year currently spent on bicycling and walking infrastructure through the Transportation Alternatives program — a total of $5 billion per year. In that scenario, the FHWA would continue setting the planning process and design standards for the roads using $50 billion per year while still excluding non-drivers. How does that shift the balance?

Every dollar spent on America’s transportation system should benefit every American. This is especially true because the roadway user fee doesn’t come close to paying for the whole program requiring all of us to cover the bill. For our investment, we should see a return in every dollar benefitting people who bike, walk, or take transit. That only happens when we break down silos, not create new ones.

For Americans to feel this change on the ground, advocates for active transportation, the environment, and equity need to look beyond retrofitting mistakes that make our roads unsafe for those outside of a car, more polluting, and less of a means of access to opportunity. While seeking a separate Active Transportation Administration (or a mobility or research agency) may sound like an innovative idea, we firmly believe that exiling non-drivers off to the jurisdiction of a separate administration will not create safe, convenient, and just mobility for people of all travel modes across the transportation system. We need to look at system-wide policy and spending changes that help address the bigger issues of safety, racial equity and climate change. We will be working with our partners to push the Biden administration and the 117th Congress to do just that.

Beth Osborne is the director of Transportation For America. Marisa Jones is policy and partnerships director for Safe Routes Partnership. Caron Whitaker is vice president, Government Relations for the League of American Bicyclists.