Cross the street in an American city, and few things will have a bigger impact on your chances of making it to the other side alive than the presence of a simple crosswalk, traffic light, or stop sign. The manual that sets the standard for such things is getting its first revision of the Vision Zero era — which could mean safer streets for pedestrians or simply better markings for robocars.

Following an outpouring from advocates across the country, the Federal Highway Administration recently announced that it will extend the deadline for public comment to May 15 on the next edition of the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which sets federal standards for the signs, markings and signals that help instruct road users on how to safely move through our communities.

The MUTCD, as it is commonly known, is the document that professionals across the country look to when they make important decisions like how many seconds a crossing signal will give a pedestrian to cross the street (3.5 seconds for every foot of roadway, in the current edition), and exactly how the crosswalk she uses to do it should be painted.

But the manual hasn't been revised since 2009 — before the advent of bikeshare, scooters, Vision Zero policies in dozens of U.S. cities., and, lest we forget, the rise of the autonomous car.

The 862 page tome (which will likely be a bit slimmer in the proposed next edition) doesn't govern everything about the dangerous way we design our roads; the "traffic control devices" in its pages are pretty much limited to paint, signs, and lights, rather than more concrete physical barriers, like bollards and curbs. And engineers aren't even legally required to follow most of the "standards" set out in its pages, unless the authors specifically note that engineers "shall" follow a particular recommendations to the letter.

Some advocates say that flexibility could be part of the problem.

"The MUTCD is not a sacred text, but it does get misused and abused," said Don Kostelec, an Idaho-based planner who wrote a guide to the MUTCD for street safety advocates who want to get involved. "About three-quarters of it is 'guidelines,' not actual, binding standards — which means in the right hands, it gives [traffic engineers] a lot of flexibility to build some good things for walkers and cyclists, and in the wrong hands, it gives them an easy out to stay, 'No.'"

But the bigger problem with the manual, Kostelec says, is that when it comes to protecting vulnerable road users, its standards aren't always high — and that helps create a transportation culture where vehicle throughput comes before safety. The document, for instance, defines a "basic" crosswalk as a set of two parallel lines of paint on the ground, when most safety experts agree that designs that include flashing signals or high-visibility paint are more likely to grab a driver's attention.

"Why don’t we default to the highest standard for safety, and let basic crosswalks be the exception?" Kostelec wonders. "Why do you need a justification to build a special hi-viz crosswalk? Change that, and the next [version of the MUTCD] could have a huge impact."

Those low standards can be even more problematic when they get dragged into court. Even though the MUTCD isn't legally binding, engineers can point to its standards to justify a dangerous road design — even though, as Kostelec aptly points out, "even an 800-plus page guide cannot account for every single roadway condition in the United States."

“When we advocate for safer streets, the MUTCD may be cited by engineers as an obstacle for making the changes needed — sometimes correctly, sometimes incorrectly,” Eileen McCarthy, a retired attorney and member of Washington, DC’s Pedestrian Advisory Council, said in a recent article for Kostelec Planning's blog. “As lay advocates we may not be able to understand every technical detail in the MUTCD, but we can develop a general working knowledge of it and use it for our own purposes and we can work with experts who are more adept with the technical details.”

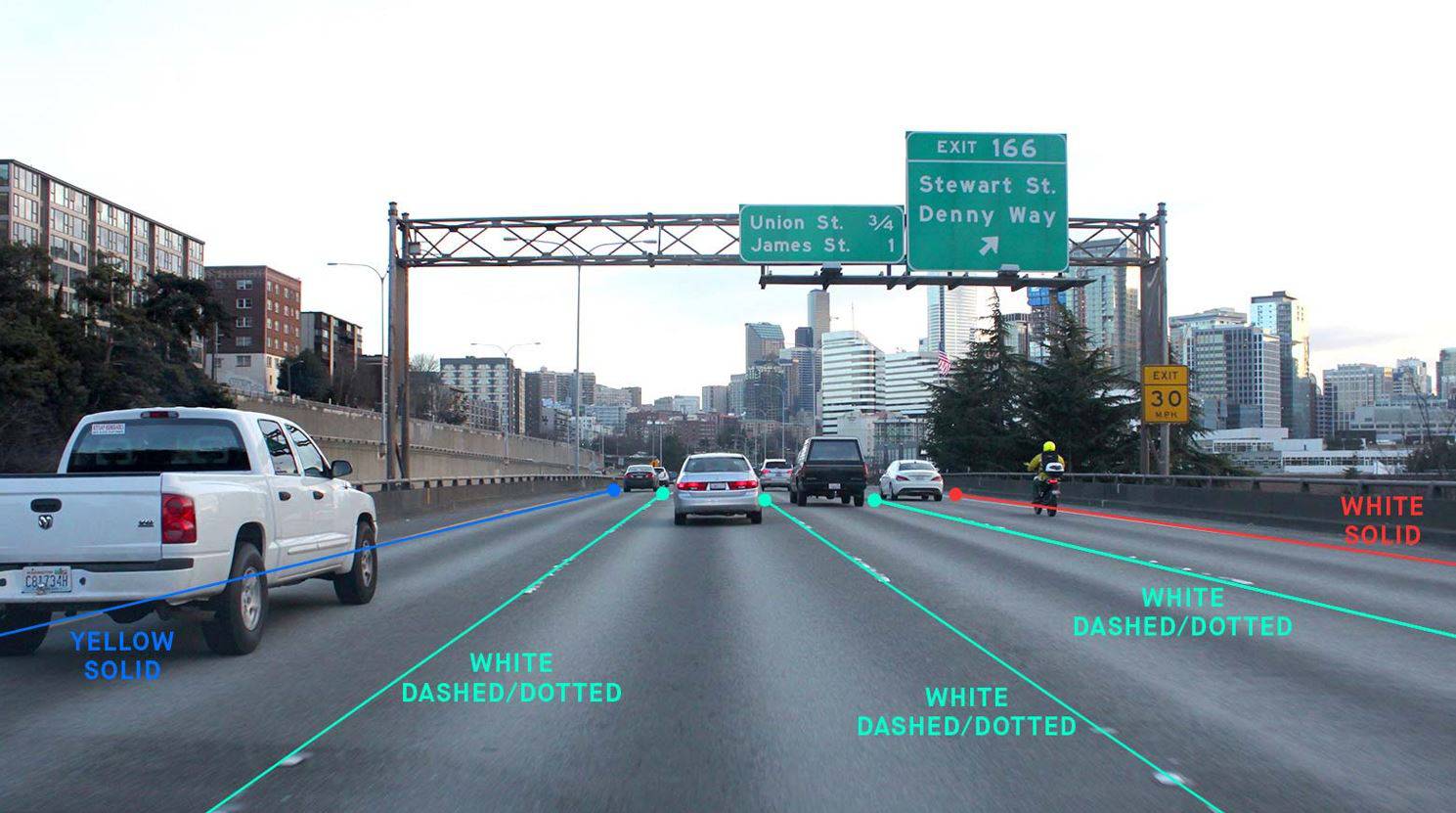

Of course, the Federal Highway Administration probably isn't revising the manual because it suddenly want bike and pedestrian advocates to have a say in how their roads are annotated. It's more likely the FHWA is doing it in response to the rise of autonomous vehicles, which rely on regular road markings to navigate complex road environments — because paint on the ground is easier for a computer to recognize than something more complex, like a human on a bike.

Indeed, there's an entire new chapter about AVs in the proposed revision of the MUTCD, and the possibility of robocars on our roads casts a shadow over much of the document. In its section about crosswalk guidelines, for instance, the FHWA specifically asks commenters to consider "the ability of machine vision of autonomous vehicles to detect accurately and react appropriately to the markings" when they make suggestions.

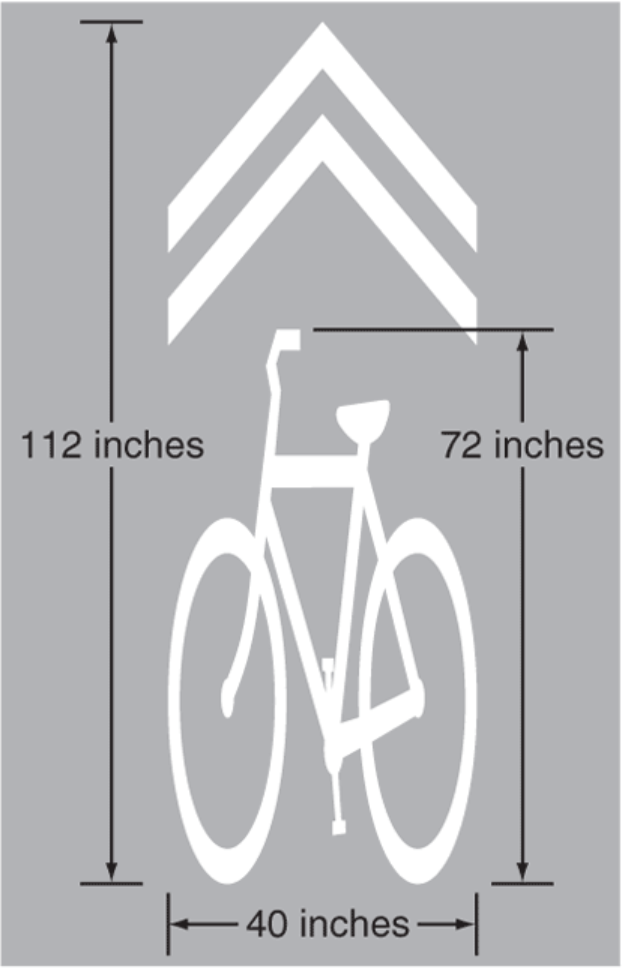

And in the section about bike lanes, it actually proposes "that bicycle facilities be segregated from other vehicle traffic using physical barriers where practicable and that road markings are needed to denote the end of a bike lane that is merged with traffic," a recommendation it makes specifically "to accommodate machine vision better."

That could be groundbreaking for cyclist safety nationwide — well, depending on your point of view. But whether it makes the final cut is up to the next FHWA administrator, and ultimately, DOT Secretary Pete Buttigieg himself.

In the meantime, advocates are urging their peers to roll up their sleeves, dive into the comments of the document, and make their voices heard.

"Most engineers are not going to stick their necks out for our ideals," said Mike Wiltsie, program director for BikeUtah. "The best way we can bring about systemic change in our streets is to change manuals like the MUTCD to better reflect the world we want and provide the cover for engineers to make it reality. We have to show up and make our perspective known."