General Motors made waves when it announced last week that it would aim to manufacture only electric vehicles by 2035 — but advocates are skeptical that the move will have much of a climate impact without a slate of accompanying policy changes.

On its surface, the news that the automaker behind many of our roadways' most notorious environmental nightmares seems like a big shift. But the path that the United States' largest car company (and its peers, should they follow suit) will need to take to net zero emissions will almost certainly be slow — drawing the public and policy focus from the quick carbon-cutting solutions that experts say we need most urgently right now.

Here are four reminders about why EVs are a harm reduction strategy rather than a real cure for our climate crisis — and why G.M., in particular, doesn't deserve a standing ovation just yet.

1. Offering EVs allows automakers to sell more gas guzzlers

Even if every automaker introduced a range of electric vehicles to dealerships tomorrow, it might not make our total vehicle fleet any greener. That's because car makers can complement those green new offerings by producing more gas-guzzlers — just like they've done for deacdes.

Many consumer don't realize that the U.S. regulates its greenhouse gas emissions on the basis of an automaker's average fuel efficiency across its entire catalog, rather than setting hard caps on the allowable emissions for individual automobile models. In practice, that means that every electric vehicle that GM introduces will give it a little more room to release a high-polluting vehicle that could erase the climate gains of the brand's "green" offerings — and if last year's record-setting truck and SUV sales are any indication, consumers are far more likely to go for the gas-guzzler.

Put another way: the ostensibly net-zero electric Hummer could give GM legal license to sell an even dirtier original-recipe Hummer for the next 14 years if it wanted to.

If you look at the entire auto industry, that doomsday scenario isn't just theoretical. Researchers have already found small increases in fleet-average emissions thanks to the way we structure our emissions standards — and if EVs had never entered the mix, under our current messed-up rules, our net emissions would actually be lower than they are today.

Biden has already committed to restoring the tougher Obama-era fuel rules that then-President Trump rolled back. But environmental researcher John DeCicco noted in the Conversation that General Motors has been "notably silent" on strengthening those standards, which could signal that it probably won't pump the brakes on its biggest gas guzzlers right away as it crawls towards becoming a fully electric brand.

"Adopting clean-car standards that grow progressively more stringent each year and require automakers to cut CO2 emissions from all the vehicles they sell would ensure that technological promises translate to actual emission reductions," DeCicco wrote.

So would investing in non-driving modes.

2. There will still be a lot of gas-powered cars on the road

Praising an automaker for giving consumers an electric option is one thing. But actually getting drivers to trade in cars that run on fossil fuels is another — and even the most enthusiastic proponents of EVs recognize that there's no way we can decarbonize driving fast enough to curb climate change while still putting the same number of vehicle miles on our roads.

The most recent Long Term Electric Vehicle Outlook report projected that five years after GM electrifies its entire fleet, a respectable 58 percent of new cars sold will run on grid power, assuming that EVs cost about the same as gas-powered cars by 2030 worldwide, and 2022 in Europe. But even in that arguably optimistic scenario, 69 percent of the vehicle fleet would still be made up of older, gas-powered cars — and they'll still be driven for more miles than clean vehicles.

And even that 58 percent doesn't sound quite so respectable when you consider that a recent study found that EVs would need to represent 90 percent of the U.S. vehicle fleet by 2050 in order to meet our national transportation emissions goals, if we keep driving as much as we do right now. Researchers noted that absent a massive, global, and near-compulsory cash-for-clunkers program the likes of which the world has never seen, that would be pretty much impossible, and emphasized that shifting away from driving and to greener modes is a climate must.

3. We have almost nowhere to charge EVs — and not enough clean energy to fuel them

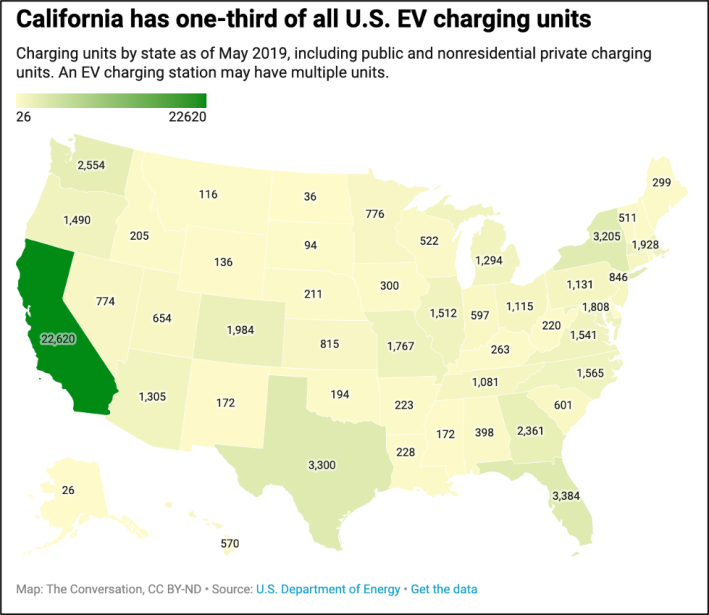

Electric vehicles have struggled to get a foothold in the U.S. partly because owners struggle to find places to plug them in. At last count, there were only 28,o00 charging stations in the entire country, and about three times as many charging outlets — but a third of them were in the state of California alone. The state of North Dakota had only 36.

In addition, a good chunk of chargers are only usable by customers of Tesla, which has developed a proprietary "supercharging" technology.

Biden has vowed to build 500,000 new charging stations by 2030, but there are few details available about how his administration will accomplish that feat. To date, most chargers have been installed by a hodgepodge of municipalities, private companies, and EV owners themselves; there is no single government body responsible for standardizing the new technology, or making thoughtful plans about how stations should be distributed throughout our communities.

“There's a chicken-and-egg problem here,” said UC Davis researcher Hermant Bhargava explained in a recent article. “Charging station providers will not invest huge amount of money in stations until there are enough cars on the road. But you won't have mass sales of cars until there are enough stations."

This is my partner and 6 year old walking in the the road because this car needed charging #caraddiction #activetravel #electriccarsarenottheanswer pic.twitter.com/icorbKPJhI

— Anna Moore - she/her (@annamoore83) January 31, 2021

And then there's the problem of how to build a clean electric grid that could handle a massive influx of new EV drivers looking to fuel up. Experts think that it is possible to retrofit our existing grid to be cleaner, more powerful, and better at managing the unique, 24-hour energy demands of vehicle chargers. But it won't be easy, and will take a massive federal investment that no one has yet been able to calculate.

General Motors' big announcement mentioned that the company would work with charging company EVGo to bring 2,700 new fast chargers by the end of 2025, which is a modest start. But no automaker has yet stepped forward to help address the demands that electric vehicles would place on the grid if more Americans actually drove them.

We should absolutely still build out our national vehicle charging capacity, of course. But we simply can't afford to do it at the expense of investing in cheaper, greener modes that won't require us to retrofit the utility sector just to get off the ground.

4. Electric cars are still cars — and cars kill

It cannot be repeated enough that while electric cars are an important harm reduction strategy for our climate crisis, the effort will do absolutely nothing to slow the other global crisis that's killing over a million people every year: the traffic violence pandemic.

So yes: let's give General Motors some tentative praise for volunteering to electrify its fleet before the government forces them to do it, as some think it inevitably will. But never forget that when it does, GM will still be selling a product that was involved in the preventable deaths of over 38,000 U.S. residents in 2019 alone — and it will keep doing it until regulators force them to make cars safer for everyone, and until legislators adopt policies that make life without cars possible for more people.