The persistent myth that it just costs more to build train lines in the U.S. than it does abroad is mostly bunk, a new analysis finds — but costs quickly balloon when we start building them underground, for reasons that researchers can't yet fully explain.

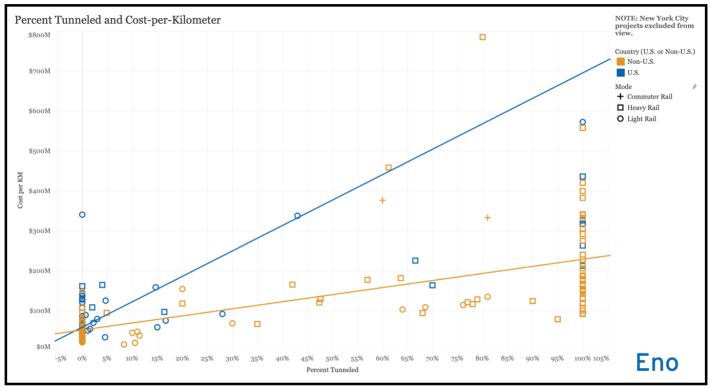

In a preliminary analysis of more than 171 intracity light and heavy rail projects in America and abroad — one of the most comprehensive studies of transit construction costs to date — the Eno Center for Transportation found that the average U.S. rail project costs $107 million per kilometer of track, or about 22 percent less than comparable international projects. And contrary to popular belief, light rail that carries fewer passenger is actually not substantially cheaper to build than heavy rail that can move a lot of people and goods.

The researchers were careful to note that they excluded two outlier mega-projects in New York City to get to their numbers. (Looking at you, Second Avenue subway and the 7 line extension.) But the findings still challenge decades of speculation based on smaller data sets that other countries are just better at stretching their transit dollars than Americans, whether because they pay poverty wages to construction workers or have fewer union-sponsored work rules that hinder the productivity of construction crews.

But there's one big asterisk to this busted myth: when Americans put their train lines anywhere but flat on the ground — often the best approach in dense downtowns that need frequent rail service the most — costs quickly get out of control.

Whether elevated or underground, nearly all the cities in the Eno database paid a premium for building their rail line anywhere but at grade. And the costs really climb once you go underground: a U.S. subway line with at least 80 percent of its track below surface level costs a staggering average of $354 million per kilometer, compared to $215 million per kilometer abroad.

That's a staggering 65-percent cost difference — and it may be a conservative number. When the researchers kept those two gargantuan, entirely underground New York City projects in the data mix, the per-mile cost skyrocketed to a jaw-dropping $756 million per kilometer.

So why, exactly, is it so much more expensive to dig a tunnel under an American city than under a European or Asian one? The Eno researchers say further study is needed, but it probably doesn't have as much to do with stuff like trade wars over Chinese steel than some people might think.

"The cost of steel and [other raw materials common to transit construction projects] are about the same in Paris as they are in New York City as they are in Seattle, because they're all globalized commodities," said Paul Lewis, vice president of policy and finance for Eno and the co-author of the report. "And materials alone can't explain why tunnels are so much more expensive here than abroad — sometimes by a factor of 10."

Building lots of stations to put transit in reach of all residents isn't the culprit, either. The researchers found that most of the stateside projects in their database chose to place their stations somewhere between one to three kilometers apart, which was much less dense international train lines, which placed them between 0.4 and one kilometer apart; still, on a cost-per-station basis, the international projects were often more affordable than American ones.

"A lot of the literature out there says that stations are expensive, and the more of them you have, the more expensive your line is going to be," Lewis said. "But the European examples in our database, in particular, tend to have more closely based stations, and at the same time, their costs tend to be lower than the U.S. ... I think it’s because European stations aren't always as elegant as what we build in the United States, and the standards for safety, like ventilation or fire escapes or those kinds of things, aren’t always as high. I'm not saying that's a good thing or a bad thing, but it's something to investigate."

The Eno researchers suspect American staffing costs might partly explain the high price tag on boring projects — and the hard-won wages of union construction workers aren't nearly as big a problem as Washington bureaucracy, or our federal tendency to underfund mass modes.

"Transit tends to have more support generally abroad, that can definitely make expensive things like environmental review processes easier and cheaper," Lewis added. "And other researchers have found that U.S. agencies are, generally, not as efficient at managing big, complex contracts [as their international counterparts]. To be clear, that's not to cast blame on agency staff in any way; they’re overworked, and underpaid, and often deeply understaffed. But a lot of the costs of managing tunnel projects comes down the sheer capacity and expertise of the public sector staff; we, as a country, tend not to invest enough in that."

Lewis and his colleagues are still at work on a set of policy recommendations that could help address those challenges, but it's safe to say that more investment into mass transit will be key. (Though whether it comes from the federal government or state DOTs is an open question; Lewis cites the relatively low costs of transit construction in Spain, which relies primarily on provincial government dollars to fund its networks rather than national ones.) And he also hopes that advocates can use the data to illuminate the hidden drivers of transit costs that even his own team may not have considered yet.

"What we’re really hoping is to engage the activist community and have people pick it apart and challenge some of our assumptions, add new questions, and request new data points," Lewis adds.

You heard the man, you beautiful Streetsblog nerds: get on in there.