As Washington lawmakers look to big infrastructure projects to get Americans back to work after the pandemic, progressives are making the case that the money would be best spent tearing down urban highways — and reinvesting in the Black and brown communities torn apart by those bad road projects decades ago.

In a groundbreaking new policy proposal, nonprofits Transportation for America and Third Way recommended that the next administration create a new, $5-billion competitive grant program that states could draw on to tear down their misguided downtown highways and redevelop the land that's left behind in better ways.

But notably, the proposal also specifies that all that newly highway-free land would be held in trust for the benefit of the communities that surround it — communities that, often, are the direct descendants of Black and brown residents whose lives were upended when the highways were built in the first place. The groups say spending the money is essential to maximizing the antiracist potential of the major transportation investment.

"[The land trust idea] is really key to regenerating wealth in communities that highway projects helped bankrupt in the first place," said Alex Laska, transportation policy adviser at Third Way. "It's really important to talk about not just the economic benefits of highway removal, but how to make sure that the people who already live there see that benefit."

The proposal offers a kind of restorative justice redux on the "Highways to Boulevards" concept that has been popular in urbanist circles for decades. Ever since the Federal Highway Act of 1956 handed state DOTs a hefty incentive to use heavily-subsidized highway projects as a pretext to clear BIPOC neighborhoods, mobility justice advocates have argued that highway removal projects could be key to repairing the harm wrought by the urban renewal era — but worried that doing it could precipitate gentrification that could destroy Black and brown communities all over again.

Despite those well-founded fears, at least 18 American cities have already torn down urban highways, usually citing the comparatively low costs of highway removal and local redevelopment when stacked against the staggering costs of maintaining the infrastructure. The only question is whether the local economic windfalls those removals often precipitate can be channeled into the Black and brown communities that have been ravaged by highway programs in the past — and help those same communities recover from the disproportionate impacts of COVID-19.

Housing reparations, meet infrastructure reparations

Though it could fit neatly into a COVID-19 relief bill or an infrastructure stimulus bill — both of which are likely to be among the first priorities for the next administration — a highway teardown bill wouldn't just be about roadways.

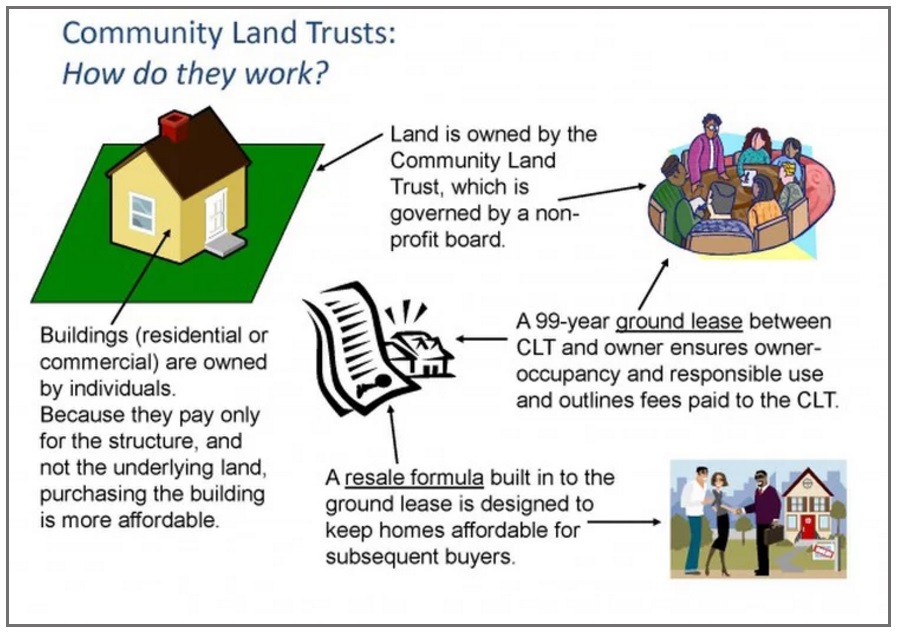

Central to T4A and Third Way's proposal is the concept of the community land trust, a land management model that can help low-income communities retain more control over their development future. Under the model, the community collectively owns and leases out the land upon which buildings in their community sit, but still allows individuals to develop and own buildings themselves. Among other benefits, the model allows the trust to set limits on things like the sale price of new developments, which can keep housing and commercial spaces affordable in perpetuity — preventing the kind of rapid gentrification by big developers that some cities have experienced when they've opened up new downtown land by tearing out a highway.

"Part of what I love about a community land trust is that they can have so many applications," said Beth Osborne, director of Transportation for America. "You could use the income from the land that you gather from the removal of the highway to help renters in the neighborhood buy their homes. You could use it to support people who were forced to move outside the area when the highway was built in the first place, and help them come back. You could use it to stoke local economic development and establish small businesses among first-time owners."

Laska and Osborne say that it's essential to bust down traditional silos separating transportation from housing — because even the best-intentioned highway teardown program could easily become a kind of urban renewal lite, despite their transportation benefits.

"We know that tearing down highways can have huge benefits for a transportation network — even if our models, for some bizarre reason, say that if you take away the highway, the drivers will just flood neighborhood streets, rather than making other choices about how and when to get around," Osborne said. (The proposal would help fix that, too, by putting $25 million towards the development of better traffic forecasting models that understand the complexities of our travel choices.) "But of course, when the supply [of highway-free, walkable neighborhoods] is artificially constrained and demand is extremely high, that creates a really valuable product. You have to actively protect land to make sure that people can afford to stay."

Where to start?

Of course, the idea of offering states money to get rid of their roadway "assets" might sound like it'd be a hard sell to our car-obsessed legislature. But Laska and Osborne emphasize that many communities are already anxious for such a program — because they recognized long ago that downtown freeways are a serious liability.

"A lot of states have already [invested in highway removal] simply because the cost of maintaining those roads is so huge," Osborne says. (One Milwaukee project, for instance, saved more than $5 million by tearing down a freeway rather than replacing it, then generated over $2 billion more in additional economic benefits on the new land.) "They aren't doing it because it's the right thing to do for Black and brown communities; they're doing it because it's a smart financial move. People want to modernize and reclaim their downtown spaces. ... They recognize that the highways their predecessors built in the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, based on the belief that the only way for retail to survive was to build a downtown highway straight through town and into the suburbs, just didn't work the way they thought they would."

Perhaps the thorniest question that awaits a highway removal program is as simple as where to start. Even the $10 billion proposed by T4A and Thirdway would only fund a "a couple of large projects and six to 10 smaller ones," in addition to community land trusts for "one to two dozen" projects, assuming some states would self-fund some or all of their own tear-downs like they do now.

To help the program have the highest possible impact, the report authors say that it's crucial that the feds help cities assess and quantify which of their highways are causing the most harm — which can also give them the tools they need to bust myths about the supposed "benefits" keeping toxic roadways up. They're recommending that government fund the creation of strong "guidance on identifying communities with infrastructure barriers, measuring the degree of harm to that community, and providing incentives and prioritizing resources to address those disparities."

And those disparities, of course, aren't always as visible a highway soundwall separating a Black neighborhood from the nearest park. Freeway removal has a major environmental impacts, too — especially in BIPOC communities with high rates of smog-induced health conditions.

"Where we put our highway determines where our air quality is worst — and we know Black communities have borne the brunt of that historically, and it's had huge impacts during the pandemic," said Laska. "Transitioning our entire auto fleet to electric vehicles would help, but that will take a long time. Highway removal and replacement will help us fight climate change and environmental racism right now."