America's top federal safety agency is raising awareness this week about safety for older drivers, but largely ignoring how car dependence often forces seniors to take the wheel even when they can no longer do so safely.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration kicked off Older Driver Safety Awareness Week on Monday with a splashy landing page urging aging Americans and their caregivers to create a "'transportation plan,' much like what many are encouraged to do for retirement." What the Administration forgot to mention, though, is that it's about as easy for a resident of an auto-centric city to make such a "plan" as it is for a person living at the federal poverty level to simply "plan" to stop working in his or her golden years — which is to say, impossible.

And according to the agency's own data, the problem is getting worse: the NHTSA reported that fatalities involving elderly male drivers have increased 36 percent between 2009 and 2018, and increased 17 percent for female drivers, a phenomenon that's likely attributable to the fact that the U.S. elderly population has swelled over the same period.

The agency has so far neglected to mention that elderly pedestrians are also among the age groups most frequently killed by drivers of all ages because of poor pedestrian infrastructure. Walking fatalities among Americans over 70 increased a whopping 53 percent over the last decade.

It’s Older Driver Safety Awareness Week. Take an opportunity this week to talk to your loved ones about safe driving. Find tips and resources at https://t.co/2vnm8EcrRF. #ODSAW20 pic.twitter.com/wHBxbWpJtf

— nhtsagov (@NHTSAgov) December 7, 2020

NHTSA's webpage does offer a wealth of expensive, individual solutions for seniors who'd like to stay behind the wheel — think retrofitting vehicles with adaptive equipment and driver assistance technology that can help older drivers as their abilities change — but the agency is mum on how drivers might actually pay for those changes, much less strategies for seniors to safely get around without a car at all.

That's a serious problem for a population group that has the single highest rate of fatal car crashes per mile, and who are more likely to be involved in multi-car crashes rather than single-vehicle impacts that harm only themselves. Most experts believe that some elderly drivers struggle to stay safe behind the wheel because they're disproportionately likely to have low vision, poor hearing, memory and cognitive impairments, and a range of other medical needs that can make piloting a multi-ton automobile a functional impossibility even with advanced vehicle safety technology.

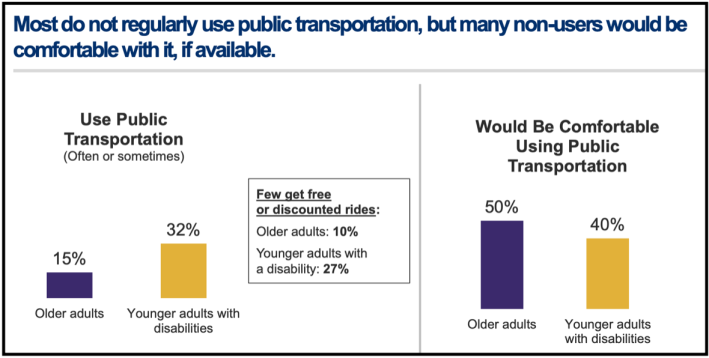

According to the most recent survey from the National Aging and Disability Transportation Center, 33 percent of Americans over 60 identify as having a disability that may make it challenging for them to operate a car, but 82 percent of them drive anyway. And that's almost certainly because 68 percent of seniors say "it would be difficult to find alternative transportation options, if they were to stop driving." (It also doesn't help that most states essentially rely on the elderly or their caregivers to self-determine when it's time to turn in their keys rather than re-testing their abilities behind the wheel; NHTSA's campaign is heavy on fact sheets that essentially asks drivers and their chosen families to assess themselves for warning signs, regardless of their medical background or lack thereof.)

Of course, there's a good reason why American communities generally shy away from getting even the least road-ready seniors to give up their licenses: the communities were built to be car-dependent. As a result, 79 percent of seniors who gave up their cars classified themselves as "somewhat" or "very" socially isolated, a 2019 study found, backing up other studies that showed a higher risk of early death stemming from seniors being unable to easily access food, work, or medical care.

The only trouble is, letting a medically compromised senior stay connected to his community via his coupe can easily kill him, too — as can forcing him to rely on pedestrian infrastructure that's usually not designed with the needs of a potentially slow-moving senior in mind.

Leading Pedestrian Intervals (https://t.co/cWHaUZ1kb4) give seniors more time to cross; Raised Crosswalks (https://t.co/8Dprzm04pP) make peds more visible; & Pedestrian Refuge Islands (https://t.co/TAg7kMwBCg) break a long crosswalk into shorter segments. #PedestrianSafety pic.twitter.com/WEFf58mqtK

— Federal Highway Admn (@USDOTFHWA) December 7, 2020

Today's auto-centric reality is pretty bleak for elders with mobility challenges, but our future doesn't have to be. Other communities who have done the hard work of transportation and land use reform to center the needs of seniors and other vulnerable road users have succeeded in ending traffic violence for all age groups — and since Finland's seniors aren't all just Formula One tactical driving experts, experts say there's no reason it can't happen here.

"It’s important to remember that driving is just one way to stay mobile," said Rhonda L. Shah of AAA. "Most older adults will tap into various transportation options to meet their needs [if they are available.]"

Of course, there's a persistent belief among policymakers that car-addicted American oldsters would never use other modes even if we made them available — but the National Aging and Disability Transportation Center survey busted that myth once and for all. More than 50 percent of seniors it surveyed said they'd use public transport if it were available to them affordably, and that percentage increased to 61 percent among seniors who live in small towns.

Perhaps if NHTSA invested in promoting the robust mobility alternatives that seniors want and need, the agency could stop spending taxpayer dollars making the American people "aware" of the safety challenges inherent to driving with age-related medical challenges, and start actually making road users of all ages safer. But until that happens, the agency is likely to continue pushing the kind of short-sighted, individually funded, and non-mandatory solutions that have sent crash rates among senior drivers soaring year after year.