Two Nashville men are suing the Music City for requiring them to build sidewalks outside of their respective homes that both residents say they won't use because they prefer to drive — a fight that offers a stark reminder of both the need to expand the ways we fund basic walking infrastructure in our cities, and the harsh realities of building for walkability when money is tight.

In a recent lawsuit against the metropolitan government of Nashville and Davidson County, Tenn., residents Jason Mayes and co-plaintiff James Knight — both of whom recently built new homes in the region — claimed that a local law requiring developers to include sidewalks into certain new construction projects like theirs actually violated their "civil rights." Attorneys for the men argued that the law effectively "coerces private property owners into spending thousands of dollars...to build and renovate public sidewalks, curbs, and gutters" that should be a city responsibility.

In an interview with local media, plaintiff Mayes added that because he doesn't personally rely on walking as his primary mode of transportation, he believes he should be exempt from the $8,800 the city ordered him to pay towards the city's sidewalk fund in lieu of building a sidewalk of his own, noting that “it’s frustrating to pay for something that we're not going to benefit from.” (Non-drivers, of course, can relate to that sentiment, since they subsidize the maintenance of auto-centric infrastructure in virtually every community in America, whether or not they ever buy gas or pay to register a car.)

Mayes and his co-plaintiff aren't the only ones who don't want to pay to help protect their neighbors from threats of traffic violence when they're out on foot: their suit was supported by a right-wing advocacy group called the Beacon Center of Tennessee, which opposes government regulations it views as inhibitive to personal freedoms, and has sued the city over the sidewalk ordinance before.

But there's a flip side: the story has also drawn the attention of some progressives who question why cities often rely on individual homeowners to build much of their basic public infrastructure rather than pursuing more progressive and proactive measures to connect sidewalk networks out of dedicated funds that aren't subject to pushback from drivers.

"The idea that sidewalks are the responsibility of homeowners is often driven by the financial realities of cash-starved jurisdictions who have far less pedestrian infrastructure than they really need, rather than a real analysis of the actual public benefit of that infrastructure," said Mike McGinn, executive director of America Walks. "It would be a big cultural change for municipalities, cities, towns and states to think about creating walkable places as an infrastructure investment that’s more worthy of public dollars than building, say, a new section of freeway. Sadly, I think a lot of it comes down to this: we don’t have ribbon cuttings for fixing gaps in the sidewalk."

When a sidewalk 'gap' is actually a chasm

Nashville is far from the only municipality to rely on developers to (often reluctantly) build sidewalks — nor are they the only city whose developers almost never have to support the construction or maintenance of the car-dominated road beyond that skinny concrete strip.

More and bigger roads for drivers, of course, have long been seen as an unquestionable public good whose construction has been almost exclusively funded by federal dollars, with more and more of the maintenance burden for those roads falling on state and local general funds, as well as government debt (rather than driver-focused fees, like gas taxes and congestion tolls). Sidewalks, by contrast, receive almost no federal funding outside of a handful of programs like Community Development Block Grants and Safe Routes to Schools, leaving cities to scrape together the money they need to protect walkers from a range of other sources — if they deign to build them at all.

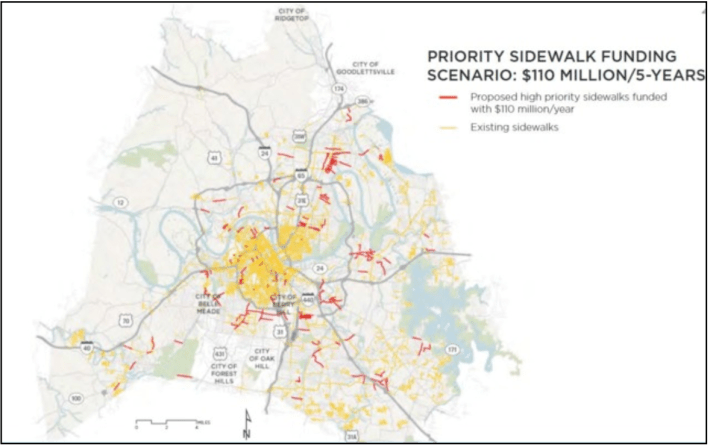

That's an especially daunting task in a city like Nashville, which has operated under a consolidated government with suburban Davidson County since 1963. Only about 19 percent of streets in the region had any walking infrastructure in 2017, when the sidewalk ordinance currently under fire went into effect.

But local leaders stress that the community has all but issued the government a mandate to protect its walkers — even if the challenges of doing it with few funding options at the federal, state or local level are almost as massive as the gaps in the walking network they have now.

"When we made our countywide general plan [Nashville Next] in 2015," said Councilwoman Angie Henderson, the lead sponsor on the sidewalk bill. "We did a ton of community engagement, and all throughout that process, it was just 'sidewalks, sidewalks, sidewalks,' And it wasn't just from people who walk for most of their transportation needs. You can't take the bus if you can't walk to it. If you can only drive to the park, that's not really great for a park system. All of our robust public engagement kept coming back to how badly our citizens wanted and needed more walkable communities — and this legislation was built on that community response."

Henderson's sidewalk bill was cosponsored by 37 of 40 of her fellow councilmembers — something that she says is "unheard of for a very complex, far-reaching piece of legislation like this." And part of its success has to do with the measure's careful efforts to balance the needs of public safety with the tough realities of a retrofitting a deeply car-centered region — starting with the areas where walkers are most likely to die.

"We did not just say, 70 years after we built the suburbs, 'Well, now we're just going to willy-nilly require sidewalks everywhere overnight,'" Henderson said. "We required sidewalks in strategic places: ones that would improve access to transit, or access to suburban downtowns, and on arterials and collector streets with high speed limits that endanger pedestrians."

And even after all that triage, many Nashville developers still don't have to build sidewalks near their properties; Henderson says the city is generous about offering reasonable variances when the geography of a site simply doesn't allow for walking infrastructure to be reasonably built, and they sometimes even forgive in-lieu contributions for developers facing certain financial hardships like extensive flood damage. And she's definitely not buying Knight and Mayes' claims that Metro is treading on their civil rights by obligating them to chip in to protect their neighbors from drivers.

"When I hear about [these lawsuits,] I just want to say, 'No. You had a choice. You could build a sidewalk, or contribute a fee in lieu of construction,'" Henderson said. "That's a very fair, transparent calculation that's part of a very nuanced policy, and cities across the country have similar ones. ... It's not some out-of-left-field, heinous, burdensome thing."

Other Nashville advocates agree — and emphasize that beyond the sidewalk realm, there's a longer, largely unquestioned tradition of requiring developers to invest in public safety when they build. A homeowner may not plan to "use" stormwater management infrastructure on their property day-to-day, for instance, but when a historic flood comes, that infrastructure will help protect their neighbors' property from devastating damage every bit as much as it protects their own homes — just like adequate pedestrian infrastructure can save communities millions in collectively-shouldered crash costs.

"When you develop a lot, you have certain responsibilities to maintain the infrastructure that supports the larger city," said Lindsay Ganson, director of advocacy for Walk Bike Nashville. "Unfortunately, for decades, Nashville didn’t require owners to do that when it came to sidewalks — but now we have. Nashville is huge, diverse, 526-square-mile city that's growing fast, and we can’t expect [this policy] to appeal to everybody. But that doesn't mean we don't need it."

Where the sidewalk (network) begins

Advocates agree that the Beacon Center's attempts to overturn the local sidewalk ordinance is contemptible — but they also agree that they wish there were better ways to fund the fight against the city's pedestrian death crisis than relying on developers to complement general funds. In an ideal world, that would include not just a wider array of local funding sources for sidewalks, but ideally, the same kind of broad funding that Nashville's car-oriented projects have always enjoyed.

"Sidewalks absolutely must be funded at the state and federal level," Henderson says. "If for no other reason than the majority of our most fatal routes are state-owned. I think the onus is absolutely on the state to right-size the roadway budget, and I think a Complete Streets mandate absolutely makes sense on those state-owned roads."

But in communities like Nashville — and the countless auto-dominated cities like them across America — waiting for major reform isn't an option, because walkers are dying right now. And even if the ordinance does require developers to build some awkward-looking and disconnected sidewalks now, it won't be that way forever.

"I would love for other cities to look to this policy. I'm proud of it," Henderson said. "I think it's a really good framework to say, okay well, here you are now; you built the suburbs; you're sprawled; you have cars everywhere; you have almost no sidewalks; it's all pretty daunting. But look: you have to start somewhere, and you can."

This story has been updated for clarity.