Car-sharing services haven't much dented rates of private vehicle ownership — but an innovative Minnesota program hopes to change that.

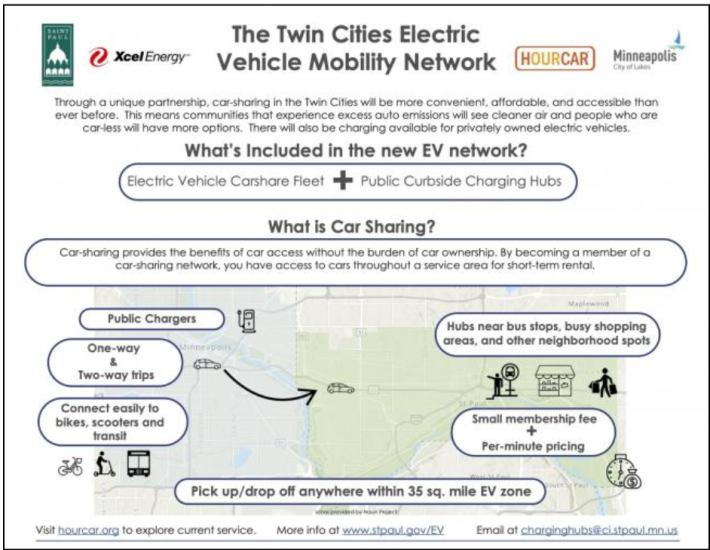

Next year, the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul will launch a short-term vehicle-rental program with electric-powered vehicles that won't have to be returned to where the driver picked them up. Advocates hope that the public-private partnership will help low-income residents of transit-scarce, polluted neighborhoods forgo car ownership.

"I am a bike and pedestrian advocate at heart, so that’s definitely gone into the planning of this program," said Samantha Henningson, who coordinates the project for the City of St. Paul. "It’s fundamentally about reducing car ownership. Lots of places aren’t well-served by transit yet, or they don't have strong biking and walking infrastructure yet — and they will someday, but they need a way to get around right now without having to own cars."

That remains to be seen. Over more than 20 years, the car-sharing industry hasn't gained traction — and it has earned a troubled reputation among sustainable transportation activists.

Why car share hasn't beat the private vehicle market

Almost every car-sharing company claims that it wants to reduce the number of private vehicles on our roads. Yet since the first major car-sharing companies began operating, in 2000, the number of private vehicles per American household has remained essentially flat, even in cities where the companies have invested heavily.

Beset by high costs and a dubious business model, the industry has struggled. By 2009, almost half of the car-sharing programs that launched in the early 2000s had shuttered. The Twin Cities' own popular Car2Go program blamed high taxes on rental car companies for its sudden decision to exit the market in 2016, just two years after the company launched.

"The high fixed costs of fleet operations, including lease expense, depreciation, parking costs, fuel costs, insurance, gain or loss on disposal of vehicles, accidents, repairs and maintenance as well as employee-related costs, squeeze the margins of the business," wrote start-up expert Tiffany Stone.

In some cities, the companies' cars aren't shared much, which tends to drive up prices. In a recent impact report, car-sharing giant Zipcar noted that its New York City vehicles were used by just 15 unique users per month, and did not disclose how many distinct trips those users took. That's a fraction of riders compared to those in the average New York City subway car; even the least popular stations in the network received at least 300 MetroCard swipes every day before COVID-19.

And most people still aren't likely to use shared cars as an alternative to buying a car — even when it saves drivers money. Many sprawling U.S. cities require constant car usage; the convenience of a personal vehicle outweighs the cost savings of a car-sharing membership — especially if that car must be dropped back off wherever it was picked up.

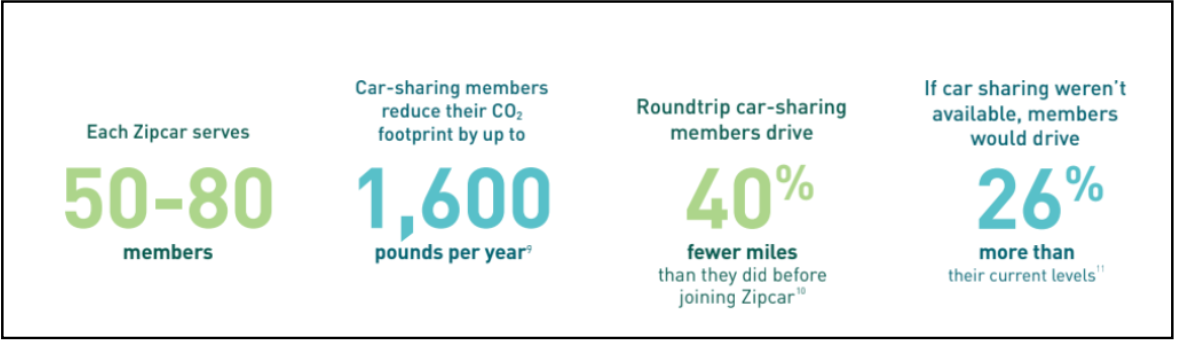

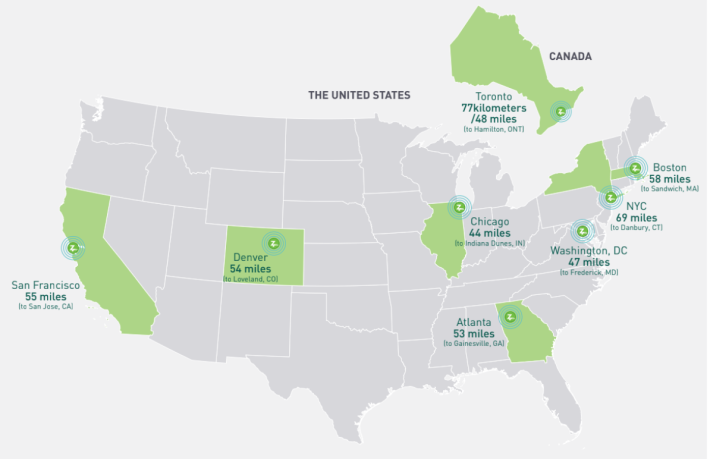

Zipcar, the longest-running, largest U.S. private car-sharing company, has thrived in part because it didn't try to tempt daily auto commuters into ditching their cars, but rather sought to give the occasional driver in a transit-rich city an affordable option for the odd trip. A recent Zipcar impact report showed that the average trip clocked in at nine hours and covered 52 miles — almost like that of a standard rental car.

"Zipcar is there for the purpose-driven trip, and we explicitly focus on what I call the three Ps — people, products or places," said Sabrina Sussman, senior manager of corporate communications for the company. "You don’t reserve a Zipcar unless you either have people going with you, or there’s a bookcase at an IKEA out of town you want to buy, or there's a place you want to reach that transit can't reasonably support — maybe going to the beach for a weekend, or to a baby shower in the suburbs.... We're trying to send the message that these are the only times you should be in the car, and the rest of the time, you should be walking, biking, or taking transit."

When car-sharing companies cater to the occasional driver, it can lessen private vehicle ownership — at least in cities with strong transit options. In a survey, 50 percent of Zipcar users said they'd postponed buying private vehicles in 2019 because of the service; the company estimates that roughly 13 personally owned vehicles are taken off the road for every shared car in its fleet.

But in car-dependent cities, the upside of car-sharing is harder to prove. In less-dense areas, Zipcar has often found most customers on college campuses — which may simply replace the informal and time-honored car-sharing model of "begging that one rich guy who lives in your dorm to let you borrow his Jeep." A sizable 30 percent of Zippers are college students, even though just 6 percent of the U.S. population are enrolled in higher education. Moreover, the company tends to place its designated parking spaces on college campuses, rather than off-campus where commuter students might use the service to get to and from class.

That doesn't help those who needs affordable, sustainable mobility alternatives most: low-income residents of transit-poor neighborhoods.

Building a car-sharing program for the transportation-deprived

The minds behind the Twin Cities Electric Vehicle Mobility Network hope to build a program that's accessible, affordable, 100 percent sustainable, and built to last — without subtracting from mass-transit ridership.

"Instead of building another Car2Go, we want to build Car2Stay," said Paul Schroeder, CEO of Hour Car, the city's non-profit partner, which will operate the vehicle fleet. "We want to create something that’s municipally owned and controlled and, in that way, looks a lot more like public transit than what we've seen before."

The Twin Cities are piggybacking the program on another municipal priority: enhancing a network of electric-vehicle charging infrastructure, which will primarily benefit private vehicle owners. Electrifying cars, of course, is among the least effective ways to cut transportation emissions, but building charging stations is a priority among Minneapolis and St. Paul residents. The car-sharing industry sees the network as an opportunity to launch a robust program that ultimately gives residents a strong alternative to owning.

"Cities have this chicken and egg dilemma; if you build out a bunch of [chargers], and there are no EV users, then your infrastructure languishes," Schroeder says. "But if you don’t build out electric-vehicle-supply equipment, then people won’t adopt EVs, because there’s no place to charge them, and people have that range anxiety, where they're worried about getting stranded with a dead battery....We’re hoping we can make the benefits of EVs available to people who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford them, and build a critical mass of shared cars that make those charging investments worthwhile to the city."

If their community engagement sessions are any indication, the people who stand to benefit the most from the Twin Cities project are those who benefit least from their current mobility choices — especially cars.

"A lot of things I'm hearing from people are, 'I have this car, and it rarely works, and I have to pay all this money to fix it, and I always have to move it for street cleaning. But I use it to get my brothers to school, and transit just doesn't go to our neighborhood; I really don't really have another choice,'" Henningson says. "The genesis of this program is about getting more residents, particularly those who have been historically underserved, onto a shared, low-carbon mobility option that works for them — and we want them to be able to reach it in a 10-minute walk or less."

The one-way car-sharing model, Henningson hopes, will make the cars convenient for people who might choose electric car-share over a private vehicle, but only if they aren't forced to schlep to a designated parking spot to pick one up. Users who return cars to charging hubs in popular pick-up areas will get discounts, but they can park the vehicles at any spot in the programs' service area, including outside their front doors. That's a plus for one of the most common one-way car-share uses: grocery shopping.

"The midway Target is definitely our biggest destination right now," Henningson laughs.

But Henningson and her colleagues are optimistic that the Twin Cities' new EVs will connect Minnesotans with greener modes, such as biking and transit.

"We’re definitely planning to put bike racks at the hubs to support multimodal access," said Schroeder. "And we're definitely working closely with metro transit on this project; we want people people can to use these vehicles to shorten their trip on transit, by, say, driving the first leg, but then getting on bus rapid transit to save money and time at the end...We know it’s a little counter-intuitive to use cars to take cars off the street, but there’s research out there that suggests this can work. Most people say, well, I don't actually need a car most of the time, but you can't buy half a car, so I guess I'm stuck owning one. Car-sharing says, well, you can actually have 0.3 cars. We can help with that."