The bean counters have spoken: A safe network of protected bike lanes is good for the urban economy.

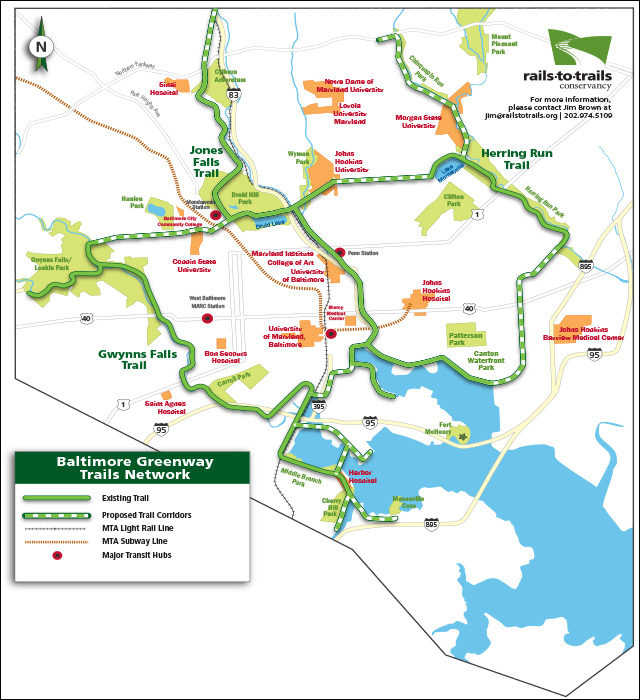

Completion of the long-sought 35-mile Baltimore Greenway Trails Network would create jobs, improve property values, reduce vehicle miles traveled, create new business activity surrounding the trail and just be better for the air, according to a new report to be released today by the accounting firm Ernst and Young.

And the green visors even put price tags on the benefits of spending an estimated $28 million to complete the last 10 miles of the project (see map below):

- Economic output generated from construction itself: $48 million.

- Property value increase: $314 million.

- More walking and biking: 6.9 million trips per year.

- New transit trips: 700,000 per year.

- Drop in car miles traveled: 8.6 million per year.

- Health cost savings because of all of the above: $2.4 million per year.

- New business activity along or near the trail: $113 million per year.

The report was prepared for the Greater Washington Partnership and the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy.

“The COVID pandemic is accelerating inequities and has shown how essential equal access to active transportation infrastructure is to our collective well-being,” said JB Holston, CEO of the Partnership. “The Greenway Trails Network is a critical, sustainable solution that will catalyze inclusive economic growth, which is the path forward toward a stronger Capital Region. The GWP is committed to completion of the trail network with our partners.”

Report or not, completion is hardly assured. The network has been a dream for many Baltimoreans since the early 1900s, when John Charles Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted (the Central and Prospect Park guy) proposed multi-modal routes to link many of Charm City's recreational attractions (car drivers got their roads, but the rest of us did not).

The Baltimore Sun reported in 2017 that the project still needed the last 10 miles. More than three years later, it still does. Once the final 10 miles are completed, the network will link about 80 neighborhoods, 4,000 acres of green space, universities, the Inner Harbor, and other destinations around Baltimore, the Baltimore Greenway Trails Coalition Project Manager Ethan Abbott recently told Blue Ridge Outdoors magazine.

Boosters also say it would connect residents to job and education centers. They believe that planning, design, and construction can occur within four years. Brandon Scott, the Democratic nominee for mayor who is expected to be handily elected in November, is a strong supporter of completing the trail. But his city, like most urban areas in America right now, faces substantial fiscal restraints.

And all cities must address decades or even centuries-old legacies of inequity in planning. In many cities, for example, the best bike route to connect tourist or recreational attractions is not always the best one to help get workers to their jobs. Anyone touting a bike lane network as a cure for city ills need only look at Atlanta's Beltline, which was blamed for increasing property values along its route — to the detriment of struggling communities.

Joe McAndrew, the managing director for transportation at the Greater Washington Partnership, said his group — a civic alliance of CEOs in the area between Baltimore and Richmond — was keenly aware that top-down planning won't work.

"The Atlanta Beltline is a widely successful trail, but it did not achieve its equity goal," McAndrew said. "In Baltimore, we're fortunate to have learned from that and from the 11th Street Bridge park project in Washington D.C. so that we can invest in the community and meet with the community. We've had early conversations with local groups in Baltimore about a development plan. Ideally, before we break ground on these last 10 miles, we will have completed a plan to make sure there is no displacement. The goal is to get ahead of it now."