Poor and non-White Americans have the fewest jobs available to them within a 30-minute transit commute of their homes — and getting to work on the third shift is even harder, a new study finds.

In a study of four U.S. cities, analysts at the Urban Institute located neighborhoods with the highest concentrations of jobs within a reasonable 30-minute public transit commute, as well as the neighborhoods where the highest proportion of l0w-wage workers live. But when they cross-referenced those two maps, the analysts found some serious mismatches between where people looking for work actually lived, and where people could find available jobs, especially without being forced to use a car to get their quickly — even when it looked, on paper, like a lot of poor neighborhoods were connected to major job centers by a frequent bus or train line.

And when the researchers controlled for how many unemployed people were actually competing for the handful of positions that could be reached on a short bus ride from their neighborhoods, the outlook got even bleaker.

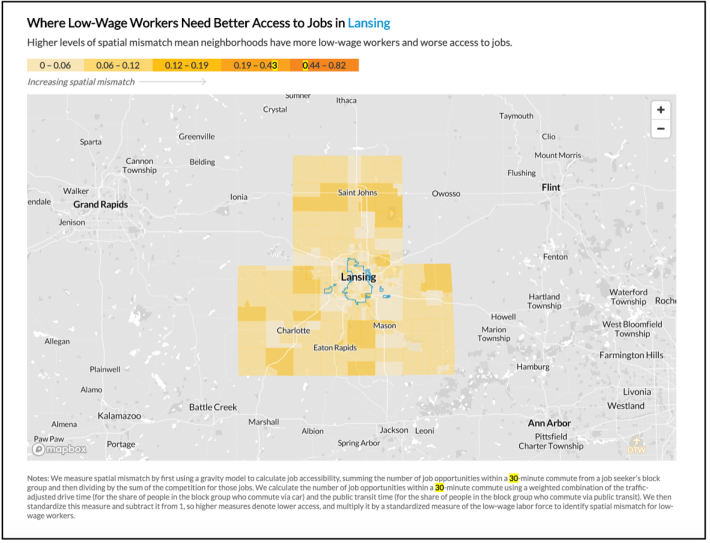

In Lansing, Mich., for instance, roughly one third of neighborhoods had high levels of "spatial mismatch" — a rough shorthand for places where it's especially hard for a person who needs a job to get safe, affordable transportation to places where those jobs are actually located and companies are actually hiring.

It's a perfect illustration of why, "to some communities, particularly those who have been historically victimized by the transportation planning and decision-making process, the transportation system can be viewed as a weapon pointed directly at them," former Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx noted in the report.

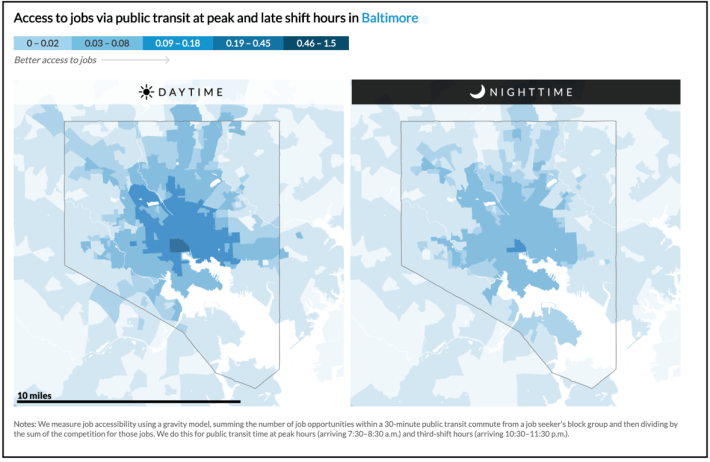

As night falls, though, getting to work gets even tougher.

As transit frequency slows down after dark, the areas where predominantly low-wage workers tend to live have even less access to areas where lots of available third-shift jobs are concentrated — and a lot of those workers are clambering for a handful of off-peak positions. Check out these maps of the greater Baltimore area by day and by dark; while residents of neighborhoods in the dark-blue central core can generally access at least a few available job opportunities, folks in the suburbs are either cut off by transit, competing for scarce positions, or both.

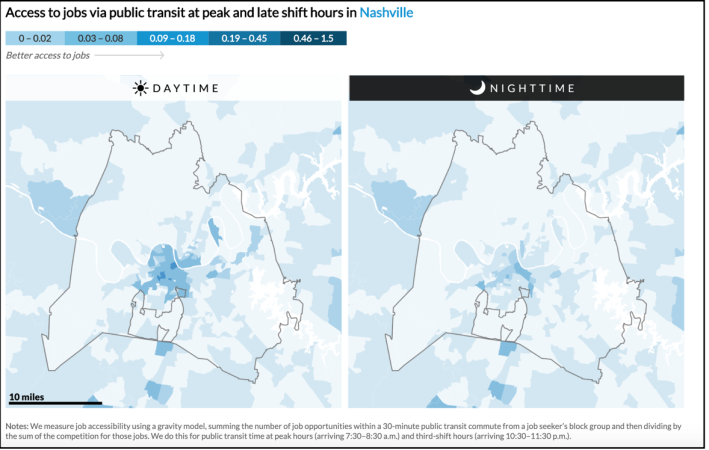

For nighttime job-seekers in the Nashville metro, it gets even harder. There are almost no available jobs for a car-free workers in the Music City. There aren't that many options available during the day, either — especially if that worker lives on the outer fringes of the region where housing is most affordable.

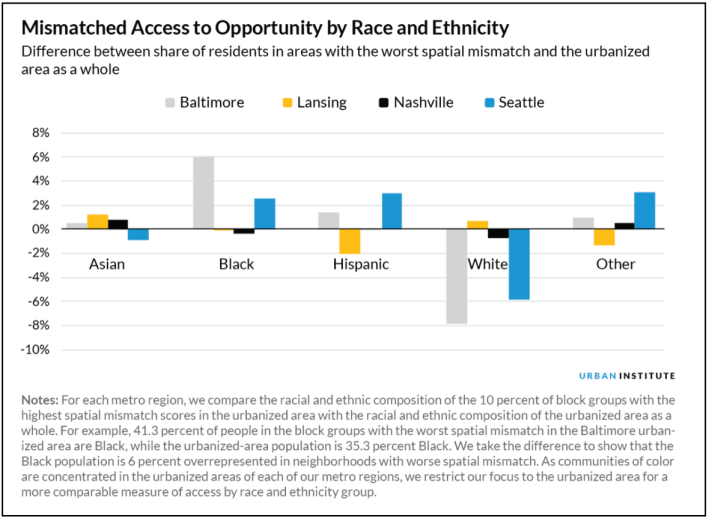

Areas with little access to jobs via transit aren't just disproportionately low-income — they're also disproportionately non-white. And that's no accident: "Highway construction and ongoing urban renewal efforts from the 1930s to 1970s destroyed and displaced many Black neighborhoods, increasing segregation, isolation, crowding, and clustering of communities of color," the report says. "In the early 2000s, the gentrification and influx of high-income residents back into many city centers subsequently pushed many low-income residents into car-dependent suburbs."

That's especially true in communities like Seattle, where White residents have better access to opportunity via transit than any other demographic group. The researchers found that the average white Seattleite who finds herself on the job market is 6 percent more likely to live in a neighborhood that's connected to good opportunities than the average of all Seattleites period. Black and Hispanic Seattleites, by contrast, had a 2.5 percent greater rate of spatial mismatch than average.

In Baltimore, the disparity was steeper. In Lansing, where concentrations of White poverty are more than 35 percent higher than the national average, white residents actually had slightly less access to opportunity than Black, Hispanic, or other people of color besides Asians.

Of course, this study only accounts for some of the most easily quantifiable barriers to accessing quality jobs. Even if a non-white worker is willing to brave a two-hour bus ride to submit an application, and beats the odds to get an interview, she'll still likely be hampered by racist hiring practices and fluctuations in her specific job market itself. The Urban Institute's study focused only on spatial mismatches between employees and employers with available jobs, not the broader forms of structural discrimination that impact the hiring process — and it used data from before COVID-19 sent unemployment numbers in many industries into the stratosphere.

But just like structural racism and the pandemic, we can change our transportation and land use policies to knock down the barriers to opportunity for the disenfranchised – and the Urban Institute argues that we have a moral obligation to do it. And it's even more crucial that leaders remove those barriers in ways that the impacted communities demand, rather than imposing even more top-down transportation solutions that they may not necessarily want.

"Metro-area leaders should make transportation and land use decisions through deep and meaningful community engagement, consulting historically overlooked communities of color, immigrants, and low-income households long before policies are proposed and at every stage of decision-making after a policy’s inception," the Urban Institute noted in the report. "Transportation policies can help reduce disparities in access to opportunity, but only if they are implemented with equity at the forefront."