Cities across America are telling the pedestrian "beg" button to bug off, thanks to thermal imaging technology designed to detect and protect human bodies on our roadways.

Last week, bike-friendly Washington County, Ore. became the latest community in the U.S. to say its investing in heat-sensing cameras at handful of its traffic lights, Bike Portland reported. But FLIR Systems, the company that installed the game-changing tech, says cities across the country are seeing the value of night-vision cameras that can spot pedestrians and cyclists, automatically activate a walk or bike signal, and dynamically adjust drivers' traffic signals to give vulnerable road users a few seconds' head start before cars start rolling.

"We're in Florida, Colorado, Arizona — pretty much any climate or condition, our technology works," said Matt Bretoi, director of sales and business development.

Forward-looking infrared cameras (or FLIRs — yes, we know it's not a perfect acronym) aren't new; if you've watched an action movie about Navy SEALs in the last 30 years, you've likely seen some version of it in action, and FLIR itself has been equipping cars with the tech to warn drivers that a pedestrian is approaching for the last 15 years.

But using the tech for traffic management is a more recent development. FLIR itself only began experimenting with adding heat vision to traffic lights around 2012 when the company acquired traffic management firm Trafficon, which provided more traditional "smart" streetlights that sensed pedestrians' movements using video technology and artificial intelligence.

But camera-based systems have some big drawbacks — namely, they don't work very well when the camera can't see clearly, when pedestrians need the most help staying visible to drivers.

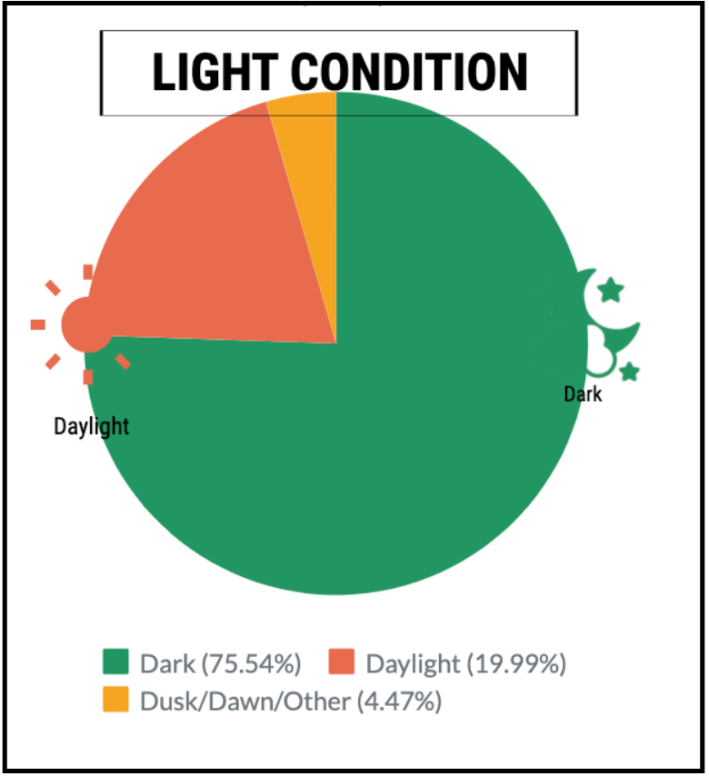

A stunning 76 percent of pedestrian crash deaths occur after dark, according to the National Safety Council. And countless other crashes are caused by other forms of "visual occlusions" that non-thermal cameras can't see around. That freight truck that pulls up next to a driver at a light, a heavy fog bank, or even simply the glare of a headlight can all be fatal ingredients in the death of a pedestrian — and that danger is increasing as American's taste for huge cars that both possess and create huge blind spots for other drivers continues to grow.

"Thermal imaging makes [pedestrian detection] a true 24 hour technology," says Bretoi. "No matter what the time of day is, or what else is on the road, the sensor will see it."

Traffic detection technology has been the subject of hot debate in the street safety world since the introduction of autonomous vehicle technology, which tends to rely on 3-D cameras and RADAR (radio detection and ranging) – neither of which are particularly good at seeing people in the dark. Some autonomous cars are equipped with LIDAR (light detection and ranging) systems, though those are imperfect in bad weather, and on their own, don't distinguish between human beings and other inanimate objects in the roadway. That's part of the reason why "driverless" car manufacturers still typically require a human driver to act as a safety back-up when she pilots her car after dark — an unacceptably imperfect workaround that's already ended in tragedy.

Thermal imaging, by contrast, is about 98 percent accurate at distinguishing among cyclists, walkers and drivers depending on whether cameras are mounted at an angle sufficient to observe the entire road, FLIR says. At that level of precision, the company argues it can be used as a better alternative to both "actuated" pedestrian crossing signals — which require vulnerable road users to push a button before they're granted the privilege of occupying a road dominated by cars, even during a global pandemic when the CDC is warning against touching public surfaces — and "fixed-time" signals, which give pedestrians the "Walk" sign at set intervals that can leave walkers waiting around for long periods.

A thermal camera, by contrast, can sense a non-driver approaching an intersection before he arrives at the crosswalk, anticipate how long it will take him to get there, and give him a brief leading pedestrian interval to cruise on through as soon as he arrives. The tech can even take note of how many cyclists, walkers and wheelchair users traverse the intersection — providing crucial, continuous traffic counts that cities often struggle to collect, even though they also struggle to plan adequate infrastructure for non-drivers without that data.

"[Our smart traffic lights] count pedestrians, and can be programmed to give them priority over drivers," Bertoi says. “Bicyclists love it, because you can roll straight through a green light without stopping to push a beg button.”

Thermal imaging has its limitations. It only provides images in low-resolution greyscale, which means thermal traffic cameras usually need to be complemented by video cameras if they're being used for enforcement purposes rather than to save pedestrian lives alone. (They also can't capture images through glass — which is great news for privacy, but not so great for determining who was actually behind the wheel when a specific car is implicated in a crime.)

And they're expensive; thermal cameras cost between $12,000 and $25,000, depending on the model, the number of sensors necessary to capture the entire intersection, and other factors. That's part of why automakers have been slow to incorporate thermal cameras into autonomous vehicles themselves, rather than as an add-on "driver's aide" on non-autonomous cars, though Bertoi notes that's changing.

And of course, there's the perennial problem of programming: cities could, theoretically, program their "smart" traffic lights to prioritize driving traffic until a certain number of pedestrians are cued up, anxious to cross the road.

But the idea of a traffic light that could be programmed to put pedestrians first, even in the middle of the night, is a seductive one for street safety advocates. And if paired with strong policy to ensure that thermal imaging is used to prioritize human safety over vehicle throughput, it could be an important tool in the arsenal to fight our pedestrian death crisis.