Decades of racist transportation policy have saturated non-white neighborhoods in heat-absorbing asphalt and shortchanged residents of those communities of greenspaces that might absorb all that heat — resulting in parks that are half the size as those in majority-white communities, a new study finds.

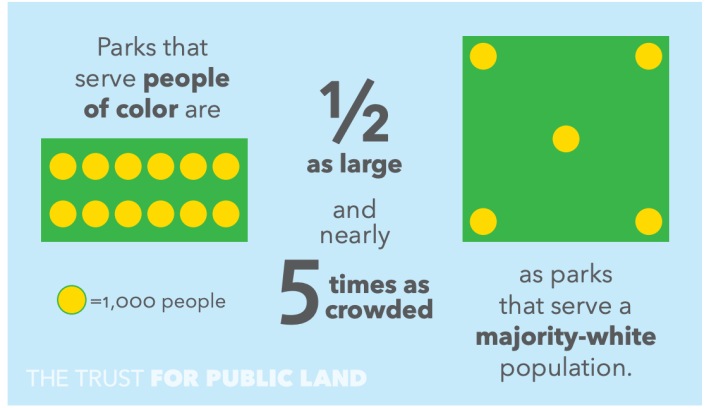

Parks that serve majority non-white populations are, on average, half as large — 45 acres compared to 87 acres, according to an analysis of 14,000 cities conducted by the Trust for Public Land.

Communities with a majority of low-income households fared even worse: their collective park space was just 25 acres in the average urban area, compared to 101 acres in richer areas.

Those discrepancies have particularly dire implications during the ongoing pandemic, when many free indoor spaces remain shuttered and residents are turning to often scarce parkland for socially-distanced recreation.

The researchers found that small parks were more likely to be located in areas with unusually high population densities and a majority of poor, non-white residents. Green spaces that serve people of color are typically five times more crowded than their white-serving counterparts, and parks that serve poor residents are four times as crowded as rich ones.

Why asphalt kills

But of course, avoiding catching coronavirus at your favorite pocket park on a busy day isn't the only health risk posed by insufficient greenspace (and over-abundant asphalt) in our cities. That's because trees can play an outsized role in regulating the temperatures of our cities overall — just as extra-wide, car-focused roads can play an outsized role in heating cities up to dangerous levels.

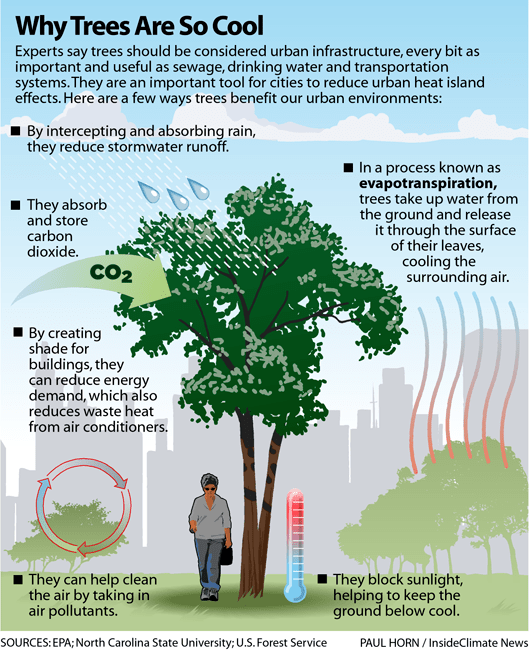

In addition to providing shade, trees act as natural air conditioners unto themselves through the process of evapotranspiration, channeling water from the ground and releasing it through the surface of their leaves, cooling the surrounding air by up to nine degrees. And a high density of trees, such as a well-planned park, can have a stunning, neighborhood-wide cooling effect: the Trust for Public Land researchers found that the ambient temperatures around homes located within a 10 minute walk of a park were as much six degrees cooler than areas located beyond that range.

Car-focused infrastructure kills

People who live in concrete jungles built around the automobile, by contrast, don't get to enjoy all that free, natural cooling — and as a result, they suffer a host of health outcomes whether or not they ever step foot on our deadly, car-clogged roads.

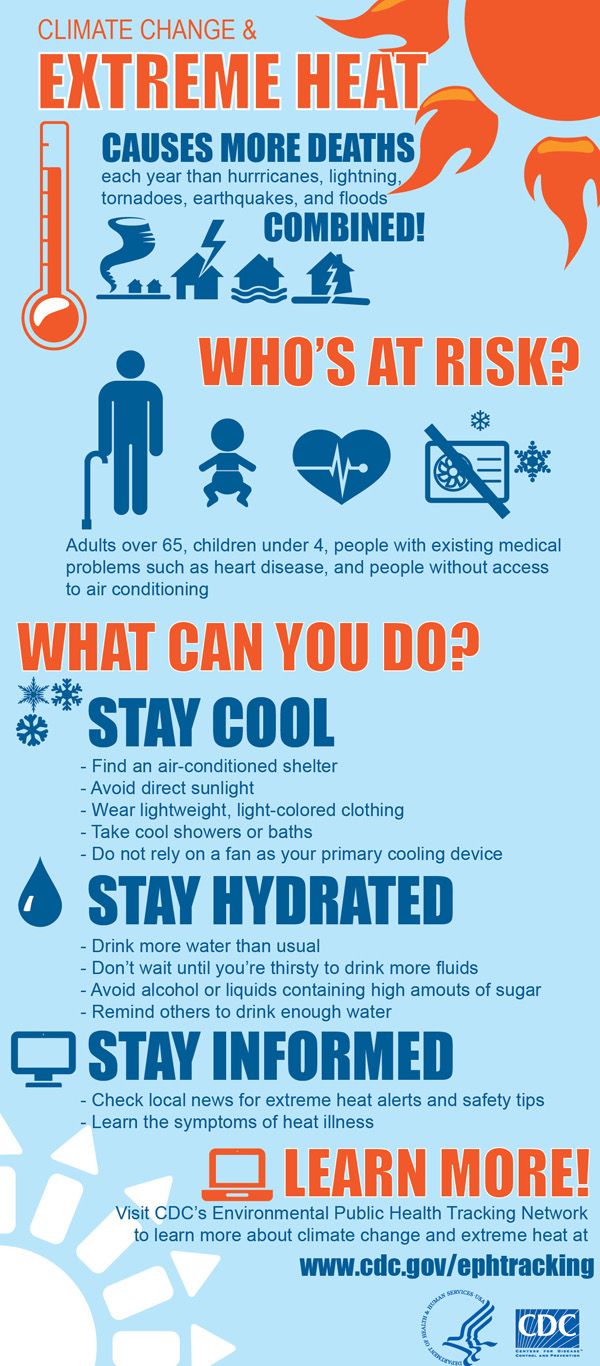

More than 65,000 people every year are admitted to an American emergency room for conditions like heat stroke and heat exhaustion, which can impede circulation and interfere with brain, lung, and kidney function, often to fatal effect. Excessive temperatures contribute to the deaths of an average of 5,600 people each year in the U.S. — a number that's just barely lower than the average 6,000 pedestrians who are killed by drivers each year. And 81 percent of those deaths happened in urban areas, largely among people who were simply existing in an over-paved city environment, rather than among rural people, for instance, who were laboring in a field on a hot day.

Even worse, modern conveniences that could theoretically cut the death toll, like air conditioning, come at a financial cost that the many residents of the hottest and most heavily-paved environments simply can't afford. Researchers have found that the phenomenon of "energy poverty" is already approaching epidemic levels in many nations, and that poor residents who adopt air conditioning see their electricity costs skyrocket an average of 35 to 42 percent.

Of course, many poor (and predominantly non-white) Americans simply have no choice but to skip the window unit and try to live with the heat — even if it literally kills them.

"In California, for instance, emergency-room visits for heat-related illnesses jumped 35 percent from 2005 to 2015, but the increases were steeper for certain groups," the researchers noted. "Hospital visits increased an average of 67 percent for Black Californians and 63 percent for Latinos; among White Californians, however, they rose only 27 percent. Urban heat islands and lack of access to air-conditioning are frequently cited as factors."

Source: CDC

How to subtract freeways

So how can we expand access to life-saving green space for non-white neighborhoods — without displacing the residents in the process?

The authors of the Trust for Public Land stress that it's crucial to learn from the racist legacies of projects like New York's Central Park (and more recent examples) and work with communities to build the kind of green spaces they want most.

“This is why a lot of us emphasize the issue of representation,” said Carolyn Finney, author of Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. “It’s not that people of color don’t care about their parks. Sometimes, it’s that no one has ever asked them what they think. Cities need to make space for their voices.”

As cities undergo the long-term collaborative process of reclaiming car-focused space to build large parks in BIPOC communities, there are still ways to cool things down in the short term. Planting trees in vacant, city-owned lots, repurposing parking spots with sod and planters, and even putting a micro-forest on a flatbed truck are all innovative options. And of course: don't forget humble street trees, which have the added benefit of calming car traffic and providing a natural barrier for pedestrians when they're planted on grass verges between sidewalks and roadways.

There is no excuse for ending the disparity in quality green space access between white and non-white communities. And as we continue to brainstorm green stimulus ideas to save our planet from climate change while getting Americans back to work, there's no better time than now.