As the nationwide protests to deliver the message that “Black Lives Matter” echo through our streets, we’re seeing a political window open for systemic change that can begin, finally, to right some of the most egregious sins of our past. Too many of our civic institutions are blind to their roles in creating and enforcing structural racism, but the growing chorus of American citizens calling for reform holds the promise of tearing these structures down, and rebuilding them in the light of true justice and equity.

Few areas of public life are more ripe for this kind of transformation than cities' land-use decisions — a process that is the foundation of the planning profession. As the founding president of the American Planning Association, I’m calling on my peers to heed the call of the protesters and move our profession into the 21st century.

Planners know our history, and can talk about its shortcomings. For example, the June and July issues of Planning Magazine include useful, brief summaries of the origins of zoning, and describe some historic use of local land-use controls to “perpetuate classism and racial segregation.”

Planners frequently advocate for the principles of racial and environmental justice in the cities where they work. But as long as the decisions that planners must implement are controlled entirely by city residents, there is very limited opportunity to achieve those principles.

For many years I have seen the continuing failure of American cities to achieve racial, social and economic justice. My own city of Berkeley, renowned for its “progressive” values and liberal politics, is no exception. Berkeley can claim credit for being a sanctuary city, for its open-mindedness and for being a birthplace of student activism. Yet for 50 years it has suppressed new housing of all kinds and now has an almost unsolvable problem of affordability and homelessness.

The very people who support progressive change elsewhere use local control of land use to prevent structural changes in their communities that would advance the cause of racial justice. These changes are essential if we are to reach our full potential as beacons of opportunity, equality, and justice.

Local control is why so much land is reserved for single-family housing — raising property values while walling off much of the city to all but the wealthy. Local control also has thwarted the development of denser communities that enable more affordable housing, ignoring the need to serve the housing needs of both new and existing residents.

Our “community engagement” processes, ostensibly designed to solicit the values and views of all residents, are instead dominated by those with the time and resources to attend public meetings. These voices are, typically, not representative of the community at large, but rather skew toward the wealthy, the white, and the privileged; the needs of would-be residents are never heard. And our cities grow more unequal, more racially segregated, and more unaffordable year after year.

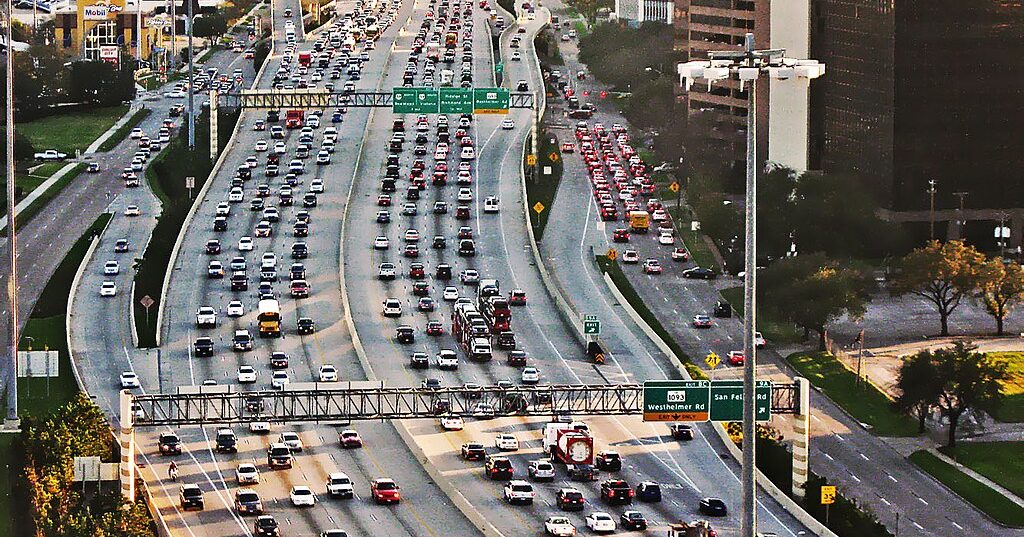

The fact is, local control over land-use decisions has obstructed efforts for racial justice and social equity in housing since the beginning of our profession. As long as the people who own land and are already housed have total control over growth and change in their communities, we will never achieve true racial justice and social equity. And, as long as local control enforces prohibitions on urban growth, we will sprawl ever-outward into green fields and agricultural lands, exacerbating climate change and land degradation.

Compact, dense, walkable cities that minimize the need for private vehicles — and make it legal to build affordable, multi-family homes in every neighborhood and near jobs, schools, and vital services — are a core component of any racial-justice agenda. Such cities are must-have solutions to climate change. And they can only be achieved with a revolution in how land-use decisions are made.

That is why I believe such decisions must be taken out of the hands of those who benefit from stopping change, and who bear none of the consequences of centering their self-interest above the interests of the disadvantaged, the disenfranchised, and the community at large. The planning profession must now play a leading role in the reformation of land-use decisions.

Today, courageous legislators in California, Oregon, Minnesota, and several other states and municipalities are leading the fight to require cities to accommodate more multi-family and affordable housing. Planners and professional leaders must support these efforts, and bring their knowledge to the fight to address our housing shortage and affordability crisis. Now is the time for planners to ask our legislators to join us in the long-overdue, deep exploration of the foundations of planning —and the difficult process of redefining how, and by whom, our land-use decisions are controlled.

As the founding president of APA, I denounce the racially unjust visions, policies and consequences that were associated with the foundations of our profession. I call on planners across the country to join me in envisioning the kinds of communities that will bring true racial justice to our oppressed neighbors of color, and to engage as allies in the fight to achieve those communities. Our role should be central in the battle against climate change; we must stand side by side with far-sighted legislators who share our commitment to housing equity and climate justice.

At this moment of crisis and opportunity, planners should be leading the way to identify constructive ways for cities, regions, and states to re-imagine how we make land-use decisions, with the goal of achieving the just, equitable and sustainable future we all desire — and deserve.

Dorothy Walker, a retired planner and former assistant vice chancellor for property development at University of California, Berkeley, was the founding president of the American Planning Association. A long-time resident of Berkeley, she served on commissions and committees on desegregating public schools, traffic and circulation, housing and development, and downtown revitalization.