The COVID-19 pandemic has changed American driving habits so much that traffic volumes may never recover, a new study finds — but the predicted the post-vaccine 9.2-percent drop in national vehicle miles travelled could be much bigger, if we act now.

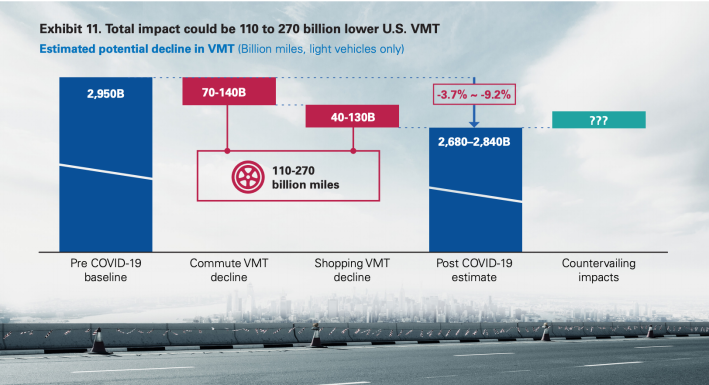

Following a comprehensive study of trends in remote work adoption, shifts to online shopping, and other national travel data collected over the course of the pandemic, researchers at KPMG concluded that traffic volumes probably aren't going to climb much higher than the benchmark they've reached to date: just 90 percent of pre-pandemic levels. Over time, researchers say that drop would translate to as much as 270 billion fewer miles driven on our roadways each year, as well as a massive drop in vehicle ownership that could take as many as 14 million distinct cars out of the national fleet entirely.

On the one hand, losing a tenth of our country's traffic miles is nothing to sneeze at.

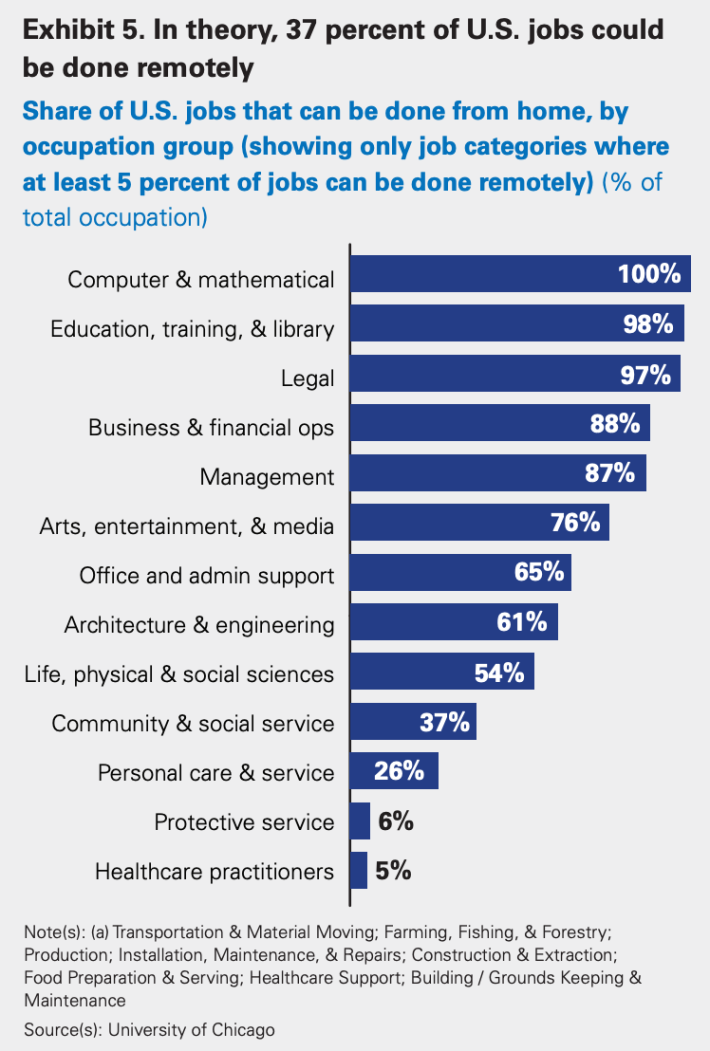

The KPMG researchers say that long-term shifts to remote work alone would reduce VMT by as much as 140 billion miles per year, albeit mostly along the corridors that were formerly travelled by wealthier, predominantly white white collar workers.

All those shopping trips Americans have been skipping during quarantine could very well result in permanent changes to consumer spending habits, too — and researchers think it could keep a lot of cars off the road, while adding a few more commercial trucks.

"In a survey of 1,100 adult consumers, 60 percent of respondents said that since COVID-19, they are doing more shopping online than in-store, vs. 44 percent before COVID-19," the report noted. "Two-thirds of respondents expect to continue purchasing items they now buy online after the coronavirus is under control."

But even these strong trends don't mean a VMT fall-off is a sure thing — and even a 10-percent drop would definitely not be enough to adequately curb transportation-related climate change emissions, end our traffic violence crisis, or remove the financial burden of car ownership from the backs of low-income Americans.

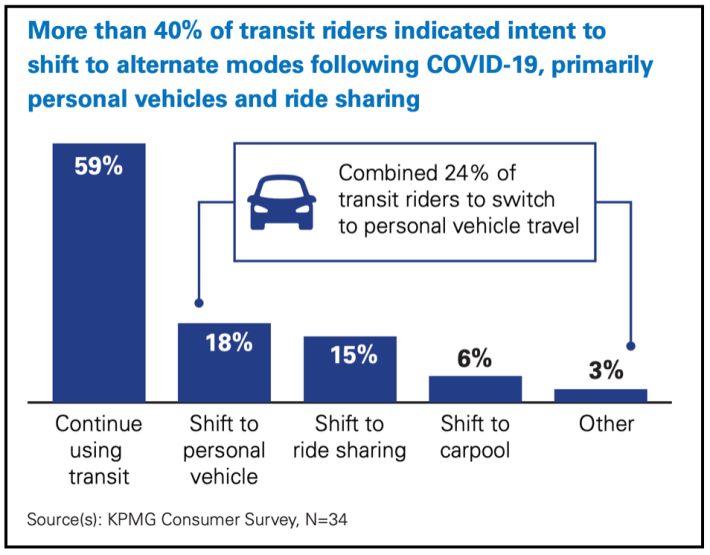

The researchers themselves warned that their own predictions could easily be undercut by several factors, including a large-scale shift away from public transportation into single-occupancy cars or even carpools. A disturbing 24 precent of transit riders are already considering making that leap.

But there are still countless things the U.S. can do right now to make sure that KPMG's VMT prediction comes true — and to exceed it.

For starters, we could retain that 24 percent of transit-wary riders by giving agencies the minimum $32 billion of funding they need to keep the trains and buses running, clean them frequently, and increase service to allow riders to spread out.

We could build the comprehensive protected infrastructure that vulnerable road users need to feel safe choosing a sustainable solo mode of transportation, rather than a single occupancy vehicle — and we could commit to doing it in a way that engages, enriches, and doesn't displace the people who live along key routes.

We could take bold, effective action to address the myriad barriers that are uniquely faced by Black, Indigenous and other people of color in our cities, from police brutality to racist vigilantism to high rates of gun violence in many underserved communities.

We could aggressively work to make sure every neighborhood is a "15-minute" neighborhood, where no resident needs to get in a car to travel to work, buy fresh food, get her kid to grade school, or visit a doctor.

As we undertake that process of neighborhood intensification, we could complement it by acting quickly to rebuild our ever-eroding social safety nets, so no low-income Americans is forced to commute to multiple far-flung jobs, or choose the cheapest childcare option available even if it's clear across town, or any of the countless other ways our car-dependent cities constantly fail the poor.

We could make use of the universe of time-tested and even radical strategies to make car travel the mode of last resort in more cities, and push ourselves to find the specific strategies that most enhance the lives of underserved populations in our deeply unique places along the way.

But what we can't afford to do is nothing — or else even that measly 10-percent drop in car travel could vanish in a heartbeat.