Nearly half of Americans think it's time to rethink how we fund our road infrastructure by switching from a federal gas tax — which theoretically rewards drivers for choosing greener cars, but doesn't always deter excessive driving itself — and replacing it with a tax based on how many miles drivers actually travel, a new survey says.

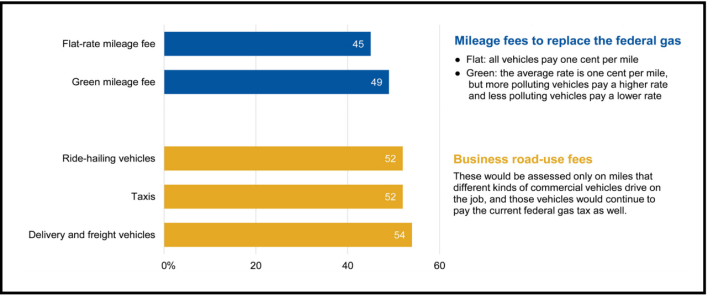

The results, which were part of an annual study conducted by the Mineta Transportation Institute, also showed that support for a vehicle mileage traveled tax are reaching record heights. Forty-five percent of respondents said they would prefer a flat mileage fee to a gas tax, while 49 percent said they'd prefer a "green" mileage fee that charges drivers of high-polluting cars a little more, and drivers of more-efficient cars a little less — the highest levels of support the researchers have found in the 10 years since the survey began.

That's an enormous amount of support for a relatively obscure idea. Vehicle miles traveled taxes are not currently in use in any state in the United States, but several communities have conducted pilot programs to study the idea, including one in California that collected drivers' mileage information via GPS technology on their cell phones, or on dedicated devices attached to their cars.

Of course, many commercial trucking and "rideshare" companies already use similar apps and devices to collect driver mileage and other information — which could make them a natural candidate for a dedicated VMT tax of their own. Between 52 and 54 percent of respondents to the survey also supported the idea of new mileage fees specifically for taxi companies and delivery vehicles, which are actually empty more than 20 percent of the miles they spend on the road. (Taxi companies like Uber and Lyft are "deadheading" more than 40 percent of the miles they travel).

What's wrong with the gas tax?

One of the reasons why the Mineta study is so significant is because it could indicate a burgeoning public awareness about our broken road funding system — one which both fails to fund the maintenance of our road network, and also fails to disincentivize excessive driving that has a deadly and expensive impact on society.

The federal gas tax was established in 1956 specifically to fund the Highway Trust Fund, which was supposed to pay for 100 percent of maintenance costs of the national road network in perpetuity. But since 1993, Congress has stubbornly refused to raise that tax to meet climbing costs — even after the Fund went into bankruptcy in 2008. Stagnant tax rates combined with steep rises in construction material prices, decades of constant road building and maintenance obligations, and the advent of the increasingly fuel-efficient and electric cars have combined to create a national fiscal emergency — and today, the Highway Trust Fund runs an average $18-billion deficit every year. The Treasury has largely filled the gap, meaning that taxpayers at large are functionally subsidizing the infrastructure costs of those who drive most.

"The public doesn’t fully recognize how much transportation funding sources have changed in the last 20-plus years," said Tony Dutzik, senior policy analyst at the Frontier Group. "Most of us, we go to the gas station, we see that we pay a gas tax, we assume that it pays for the roads that we use. But it doesn't — at least not completely."

Of course, wear and tear on highways aren't the only costs to society created by excessive driving — and the gas tax currently commits no money to addressing the expensive externalities of the mode, from accelerating climate change to our ongoing traffic violence epidemic, alongside countless other problems. Experts have long pointed out that the drivers of "green" monstrosities like the electric Hummer (or the wide range of hybrid SUVs that kill a disproportionate number of pedestrians) could save money at the pump when compared to the drivers of safer, smaller cars — savings that could be lessened if the nation switched to a better tax structure.

Hiking the gas tax, of course, could help stabilize the Highway Trust Fund — at least in theory. But many experts argue that just raising gas taxes could backfire in the long run, because high gas taxes are often obscured by low oil prices. Since the gas tax is rolled into the price tag at the pump, any drop in total fuel cost has historically incentivized drivers to hit the road more. And as fuel-efficient cars become a larger share of our national vehicle fleet, total fuel costs per household will go down even further — and so will Highway Trust Fund revenues, without the benefits of actually subtracting any drivers from the roadway.

The benefits of VMT

If a gas tax only disincentivizes burning a lot of fossil fuels, a VMT tax disincentivizes something much more simple — frequent unnecessary driving.

"To me, one of the possible benefits of a vehicle miles travelled fee is that it's more transparent to folks than a gas tax," Dutzik said. "With VMT, you at least have a meter running in your mind about how much that next mile will actually cost you, and it might discourage you from taking that car trip when you could get there another way."

Because "green" VMT is an option, electing to tax excessive driving doesn't mean we can't also tax excessive fuel consumption. And with even more finessing, they may even make it easier for governments to give a leg up to poor drivers with no choice but to drive to three jobs all over town.

Because VMT programs don't have to rely on gas station infrastructure to collect fees, they're fairly flexible. For instance, after a low income driver's onboard GPS device sends the government her mileage, the government could discount or forgive her fees based on her tax bracket, or allow her to pay on an installment plan the way she might any other utility when she falls behind on the bill. And if drivers prefer to pay directly at the gas station or charging station, some pilots even allow them to do so in cash, or via a service like Cash App or Venmo, which are increasingly popular financial options among the underbanked.

"There are valid equity concerns with a mileage fee, but here's the thing: right now, nobody budgets for the gas tax," said Asha Weinstein Agrawal, director of the National Transportation Finance Center and one of the study's co-authors. "At least with VMT, there are ways to make that price tag more visible, and plan for it."

Why VMT alone is not enough

But experts warn that even a perfect mileage fee wouldn't be a total panacea for what ails our city transportation networks. That's because it matters a lot how much those fees would actually be — and what the fees would actually pay for.

In our current system, rock-bottom gas taxes prop up an increasingly insolvent Highway Trust Fund, which itself supports a mode of travel that kills an average of 38,000 people every year. Experts say that's a stark contrast to nearly every other country in the world.

"In most nations, gas taxes simply go into a general revenue fund, and then the government decides every year what it wants to do with that money," Weinstein Agrawal said. "[The fact that the US has a dedicated Highway Trust Fund] limits our ability to make changes, and spend money on the things that people might believe are important in a given year."

But if more of our travel fees were channeled towards infrastructure for transit, walking and biking — while simultaneously funding an effort to decommission the most dangerous highways that never should have been built, like the ones we ran through countless downtowns during the urban renewal era — it could have a more positive impact than simply channeling gas taxes back into infrastructure for gas-guzzling modes. Increasing the gas tax could help even more, as could switching to a tax structure that more accurately disincentivizes excessive driving, like a VMT-based fee.

And it might be even better, some experts argue, if we implemented a suite of new taxes on drivers that accurately reflected all the negative impacts driving has on our communities.

"You could charge people for the congestion they produce, for their impacts on the road infrastructure, for the carbon they emit, and for their mileage," Dutzik said. "Fees for time on the road have even been put forward. When we posit VMT as a replacement for the gas tax, it at least addresses some of those issues, at least. "

For now, experts are heartened that the American imagination is at least beginning to expand — especially as we begin to recognize that even the most deeply embedded categories of government spending aren't set in stone.

"Saying you strongly support something on a survey does not mean you're necessarily champing at the bit to see it implemented," said Weinstein Agrawal. "But I do think there's more awareness of the fact that the transportation world is changing. At least, I think people are seeing that electric vehicles are actually coming, and there may be a lot of them, and gosh, it doesn't seem fair that those drivers should pay nothing. There seems to be this assumption in the room — and certainly in Washington — that Americans hate taxes, and, of course, you can't raise the gas tax. We're starting to realize that may not be true."