For once, something intuitive turns out to be true: near-miss car crashes are a very good predictor of actual crashes on that same roadway — and cities can save lives by changing road designs in high-conflict areas before more people die, a groundbreaking new traffic study shows.

In a first for any U.S. city, Bellevue, Wash. collected over 5,000 hours of data from a network of high-definition video cameras throughout its street network, cameras that analyzed persistent patterns of dangerous driver behavior to observe road conditions that most frequently lead to traffic "conflicts" (a.k.a.: near-miss collisions) on their streets.

The results show that crashes happen where the near-misses happen.

"To me, the best type of research is the kind that puts hard data behind something that you know in your gut," said Noah Budnick of Together for Safer Roads, which helped facilitate the study. "And in the last 20 years or so, as more and more governments have moved towards data driven-management they’re looking for better data to fulfill that 'evaluation' pillar of Vision Zero to help make roads safer."

Anonymized video traffic footage has long been a crucial page in the street safety playbook, but usually it's deployed near single road-calming projects for limited periods of time, simply to assess what's working and what's not.

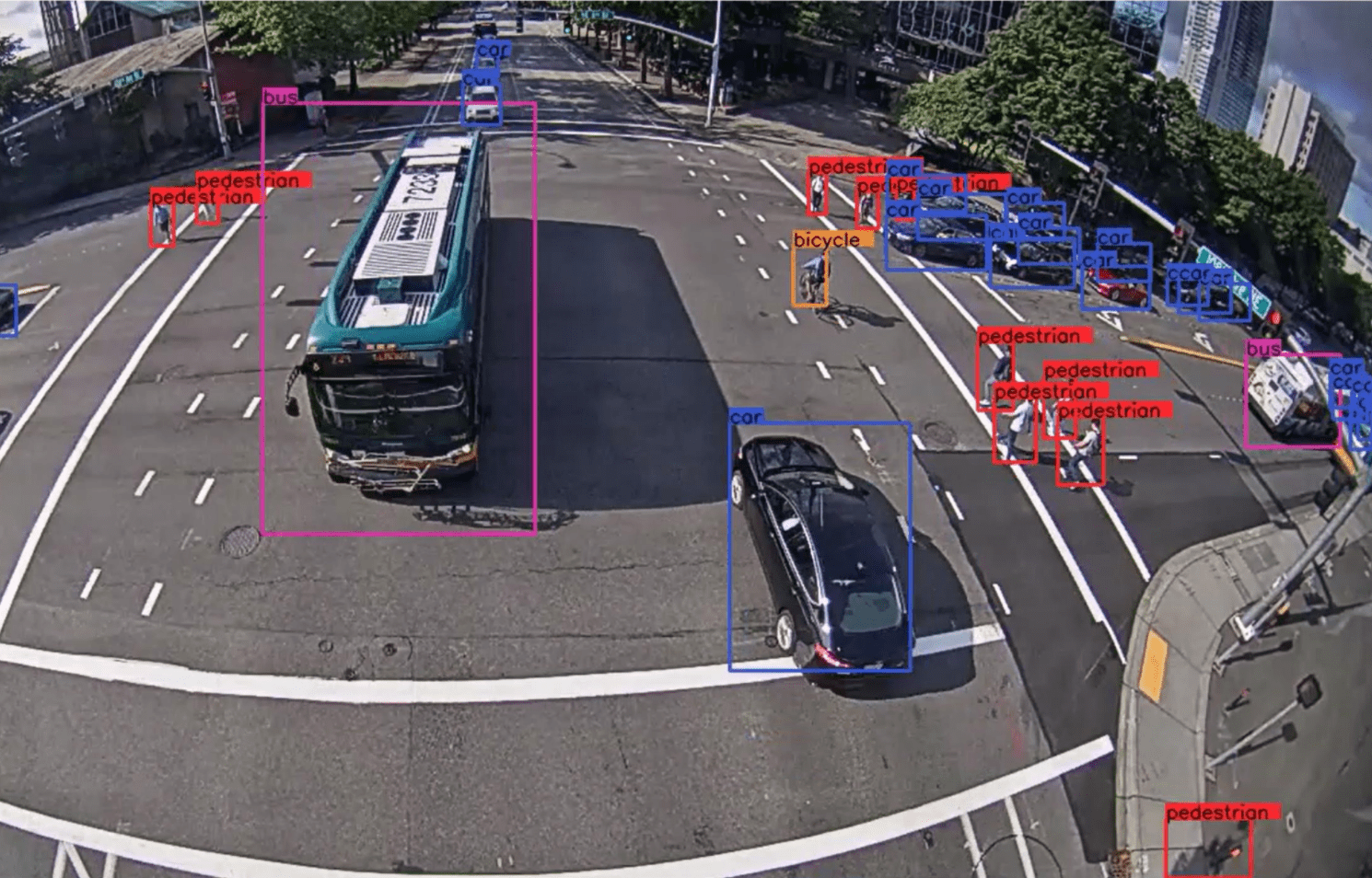

The Bellevue project was unique because it collected traffic conflict data across 40 cameras spanning an entire city— and because is used state-of-the-art artificial intelligence to isolate patterns in the data.

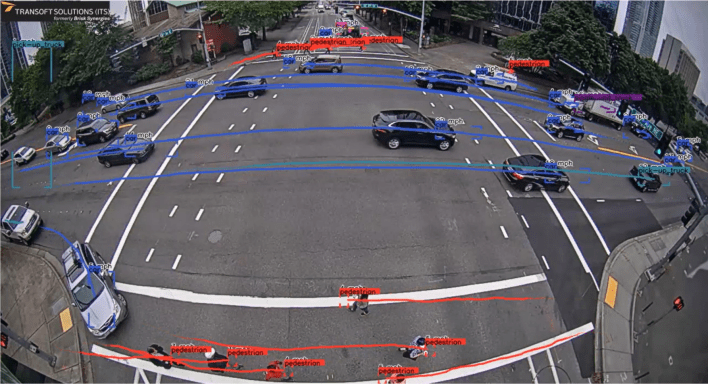

The city worked with Transoft, which automatically identifies road user types, and speeds, trajectories, and vehicle sizes — without collecting anyone's personal information. (The cameras are unable to isolate license plate information, are not equipped with facial recognition technology, and are not marketed to law enforcement agencies.)

Then, Transoft's machine learning capabilities automatically aggregates the data from throughout the study period to identify persistent driver patterns that might indicate that a lot of people are driving irresponsibly, and it may be time to change the design of the road.

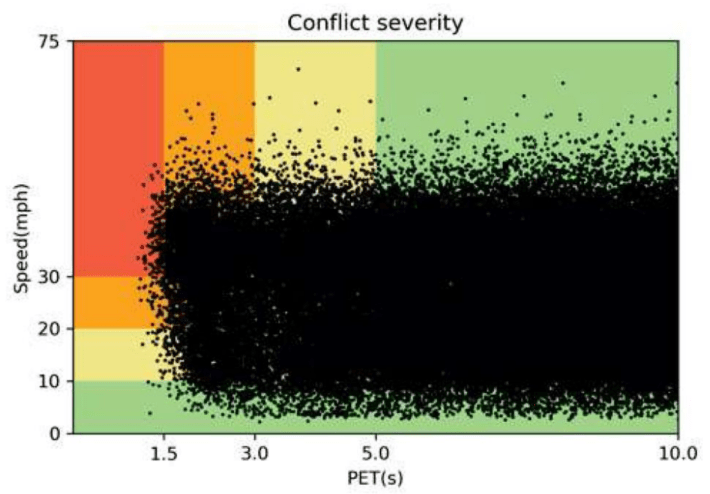

For the data nerds in the audience, here's an example of of how the software charted the severity of traffic conflicts at a single intersection; each black dot represents a distinct near-miss, and it's charted relative to the speed of the driver who initiated the conflict and her "post encroachment time" (in rough layman's terms: how near of a miss the crash was, presumably in seconds; the dots in the red quadrant represent were the closest calls.)

Transoft's tech is unique in that it enables traffic engineers to observe the actual footage of the worst traffic conflicts, while also employing machine learning to help them them quickly analyze patterns of driver behavior over time — two things that are arduous if not impossible for the people who plan our roads to access. Engineers who want to make data-focused road safety improvements in the U.S. typically are forced to rely on years of painstakingly collected car crash data sourced from police reports, which is often imperfectly reported — and even when it is rigorously collected, crash data only provides meaningful information to engineers after tons of people have already been in car crashes.

The Transoft Solutions safety analytics platform leveraged Bellevue’s traffic cameras and captured data about 20,000 serious traffic conflicts associated with 8.25 million road users in a single week.

"We don’t need to wait five years to wait for people to get hurt and become data points," said Franz Loewenherz, principal transportation planner for the city of Bellevue. "With this tech, we can get so much data that we can essentially compress five years worth of the information [we'd get from a more traditional traffic data source] into a single week. Conflicts are the canary in the coal mine; they can give us that early warning of what’s going to be a problem, so we can start thinking about ways to change the design before people get hurt."

What Lowenherz and his colleagues observed on the streets of Bellevue quantifies realities that will be sadly familiar to non-drivers across America. Cyclists, for instance, represented just 0.1 percent of observed road users on the city's streets, but were ten times more likely to be the victim of a near-miss crash than motorists. That's in part because the cameras also observed that more than 10 percent of Bellevue drivers were speeding when they passed a camera, and half of those drivers were breaking the local limit by 11 miles per hour or more.

That data helped the DOT understand why their traffic violence crisis was so disproportionately effecting pedestrians and cyclists. From 2010 to 2019, five percent of all collisions in the city of Bellevue involved non-drivers, but vulnerable road users represented a staggering 49 percent of serious injuries and fatalities, according to Lowenherz.

"What we observe of the crash data is confirmed in the conflict data," he added. "And now that we know, we can look out for persistent conflicts and make strategic changes there."

Even those who might never set foot in the city of Bellevue in their lives could potentially benefit from the first-of-its-kind study, too. That's because Transoft's software also aggregates data across all 80 cities it works with around the world, and uses that information to help make recommendations about road interventions that have actually worked.

"The more data we collect, the more we can partner with engineers to help recommend effective designs — not just for a single city, but for cities around the world," said Charles Chung, vice president for transportation safety at Transoft. "We’re producing cameras, but we're also producing a shared knowledge base that we’re able to share with other cities to save lives."

The more data points are added to that pool, the easier it will be to predict dangerous driver behavior everywhre — and implement meaningful road changes to create "self-enforcing" streets that naturally prevent drivers from killing people, while lessening the need for police intervention for behaviors like speeding. That would support a major goal of the #DefundThePolice movement and make streets more accessible for people of color who face the terrifying possibility of state violence on our roadways every day.

"Collectively, as an industry, we don't just want a data pool — we want a data lake," said Loewenherz. "We want communities all over the world to be able to say, 'I’ve got this kind of an intersection with these kinds of road features and these kinds of conflicts keep happening; which communities have something similar? What have they done? What’s worked?'...As a Vision Zero city that wants to end roadway deaths by 2030, we want to be proactive. We want to move beyond crashes as an indicator of where we should intervene. And now we can."