A Columbus, Ohio research team is getting closer to releasing an app that could soon give people with cognitive disabilities more independence on mass transit systems across America.

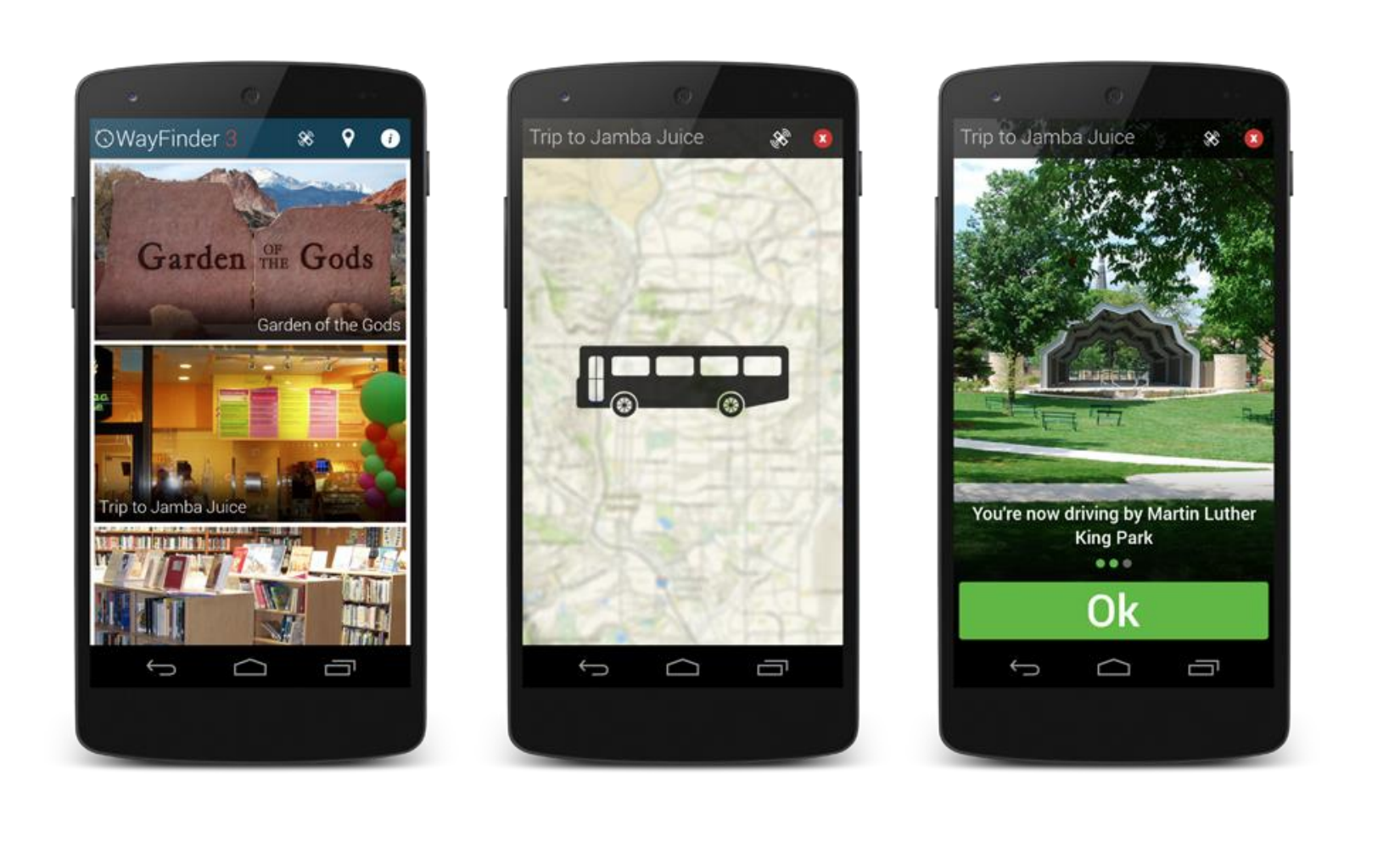

The Wayfinder app, developed by AbleLink Technologies in partnership with Smart Columbus, provides customizable support for users with cognitive difficulties, including disabilities stemming from medical conditions such as autism, stroke or traumatic brain injury. Many people with cognitive disabilities are unable to drive, but may also struggle with navigation systems on public transit that weren't designed for riders with their needs. Users of the app also reported having trouble recognizing street names, or knowing when to leave a bus at the end of their route.

These ableist oversights in the design of public transit systems can make something as simple as a bus ride frustrating and even dangerous for riders who find themselves in unfamiliar surroundings — to the point where some find they can't make independent use of public transportation at all. That's a particularly troubling barrier in less-walkable cities like Columbus.

“Columbus is a city dominated by personal vehicles, and we needed a program to assist people who have intellectual and developmental disabilities in order to help them use public transportation” said Carmen DiGiovine, director of Rehabilitation Science and Technology in the Assistive Technology Center at the Wexner Medical Center, and director of the study that proved the app’s usability.

Over the past two summers, DiGiovine’s research team recruited individuals from the disability community to help evaluate the potential app. The group partnered with the Ohio State Nisonger Center, which serves the needs of people with developmental disabilities and their families, to provide user insights. The team also worked with the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA), which provided a simulated indoor bus stop, complete with half of a full-size bus and working traffic signals for some of the testing.

The feedback from the study participants helped the developers make crucial improvements to the app’s features. The next iteration of the technology now includes flashing lights, audio prompts, and location images to provide reminders for users to get off the bus at the appropriate stop. Caregivers can even create customized routes for app users through an agency website.

But perhaps the best part of the app is how it can be adapted to the unique needs of each user.

“The best part of the app is the customization,” said Josh Cook, program developer at ARC industries, which provides access to employment opportunities and vocational training for adults with disabilities. "The web interface is easy to use and allows options such as voice recording for people with visual issues or simplified text clues for individuals with hearing problems. And because you can record your own voice, it’s also multi-lingual."

Cook also praised the Wayfinder app's ability to double as a communication tool between caregivers and riders, allowing a person at home to check on the app user's progress on their trip, and even send a message if they get off track.

“Using the app gives people [with disabilities] freedom to see more of the city,” added Cook. “It gives them more awareness of what’s happening around them.”

Most of all, DiGiovine hopes the technology will help address gaps in accessibility for the disabled community. According to the COTA website, the agency's on-demand paratransit service, Mainstream, requires an application process that can take up to 21 days — and some riders with cognitive disabilities are ultimately deemed ineligible, even under the Americans with Disabilities Act.

"Under the ADA, COTA Mainstream serves as a “safety net” for only those persons whose functional capacity imposed by their disability prevents them from riding the regular COTA bus," the agency states.

Advocates hope that creative solutions like Wayfinder might offer options to disabled Columbus residents who are denied access to paratransit services, but still struggle to use bus networks that aren't designed with their needs in mind.

“We tend to group together everyone with disabilities, whether they’re a veteran with an injury, a stroke patient, or born with a birth defect,” said DiGiovine. “They all have the same goals. They want to get outdoors. They want some independence. We can use cool technology to actually improve people’s lives.”

Melissa L. Weber, MA is a writer focused on science, health care and the environment. You can read more of her writing at melwriter.com.