Driverless cars are worse at detecting darker skin pigments, meaning that autonomous vehicles might not solve the already disproportionate pedestrian death toll faced by black communities, according to a new study.

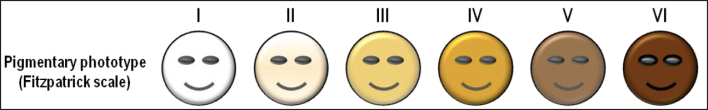

The facial and body recognition technology built into many pedestrian detection systems does not recognize and react to darker-skinned people as consistently as it does lighter-skinned people, according to the study from Georgia Tech. The researchers studied several leading technologies, and found that they were consistently between 4 and 10 percent less accurate when they encountered images of human figures with skin types four, five and six on the Fitzpatrick scale, a commonly-used scientific tool used to differentiate between human skin colors in machine learning contexts.

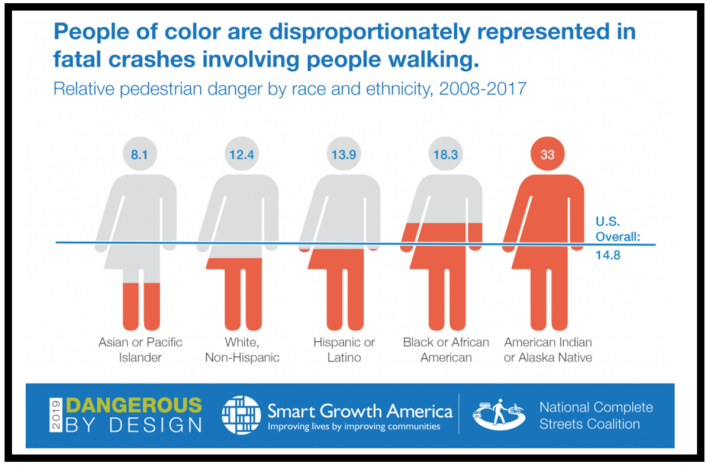

Many Black, indigenous and other people of color fall into the higher end of the Fitzpatrick scale; nationally, people of color are significantly more likely to be killed in pedestrian crashes with motor vehicles.

What may be more troubling, though, is why automated detection systems are so bad at detecting black and brown skin. Researchers point to two primary reasons — and both have to do with the inequitable data sets that companies use to train computers that are supposed to be smarter than human drivers.

First, and most outrageously: the researchers found that, on average, the training data set that many pedestrian detection systems use had roughly 3.5 times more examples of lower-Fitzpatrick scored (read: typically white) pedestrians compared to higher-ranked (Black and brown) pedestrians. Put another way: pedestrian detection systems are typically better at saving the lives of walkers who look like the walkers they've seen most often in their training models — and the computers are looking at way fewer images of dark-skinned people.

Second, researchers found that many of the data sets themselves were fairly small — and as anyone who's taken a high school statistics class knows, too-small data sets can often make for dangerous actions based on bad analysis. That's part of why people who build machine learning and artificial intelligence systems are actively working to expand the data available to train pedestrian detection systems; if you've ever "proved you're human" to your email server by picking out the crosswalk in a Captcha photograph, you probably added to an automated vehicle's training set without even knowing it. But even after years of efforts, it still hasn't been enough.

Automated vehicles might be getting incrementally smarter every day, but as countless studies before this one have flagged, they're nowhere near smart enough to be on our roads yet — even though they are on our roads anyway, and have already killed pedestrians.

And moreover, we still haven't proven that pedestrian detection systems will ever be smart enough to prevent 100 percent of car crashes and save 100 percent of pedestrian lives. A recent study from the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety found that even if every single car on the road were made autonomous tomorrow, at least 66 percent of crashes would still happen. According to the study, that's in large part because AVs just aren't up to the complex task of piloting a dangerous machine through a dangerous built environment, and require all-too-dangerous human beings, complete with their implicit racial biases, to help them out.

“AVs need not only to obey traffic laws, but also to adapt to road conditions and implement driving strategies that account for uncertainty about what other road users will do, such as driving more slowly than a human driver would in areas with high pedestrian traffic or in low-visibility conditions," the study said.

That paragraph should trouble anyone who wants drivers or "driverless" cars to stop killing Black people — and sadly, that time isn't coming anytime soon. In the short term, the best approach would be to dismantle the underlying racist causes of traffic violence that disproportionately affect communities of color — and stop hoping that miracle tech will make the problem go away.