This article is part of an ongoing series that traces the origins of American car culture and how automobiles became our default. Follow #Streetsblog101 for more.

Women buy 62 percent of all new cars in the U.S. But you wouldn’t be able to tell that by watching the average car ad.

For nearly as long as there have been automobiles, automakers have considered men their primary market — even as the wins of the feminism movement put more and more women in charge of their own checkbooks. And the rhetoric these ads use isn’t just designed to target men. It’s using the worst aspects of toxic masculinity's prevalence our culture to manipulate men, as well as people of any gender who buy into toxic masculine culture — and those attitudes spill out of the car-buying realm and into driving culture itself.

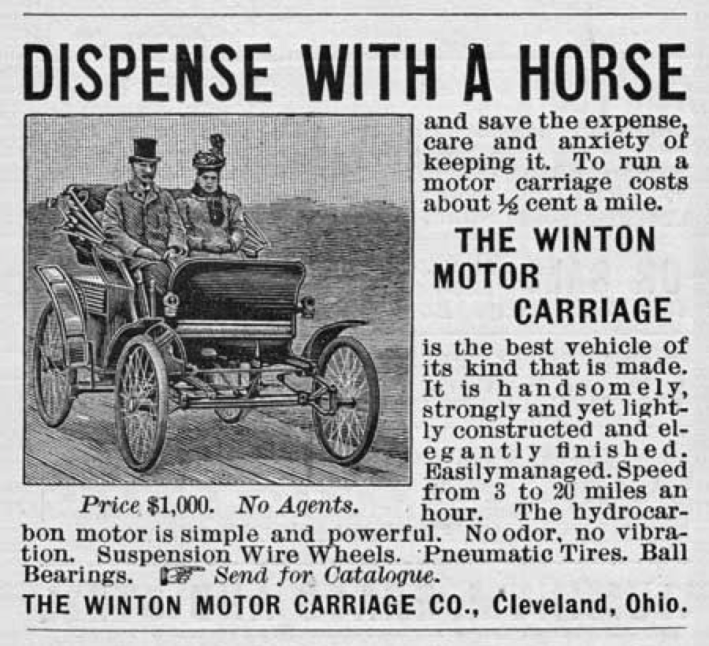

Car ads weren’t always stuffed with macho messaging and images of rugged males climbing up mountainsides in their motor chariots. The earliest automotive commercials emphasized the practical benefits of making the switch from horseback to horsepower:

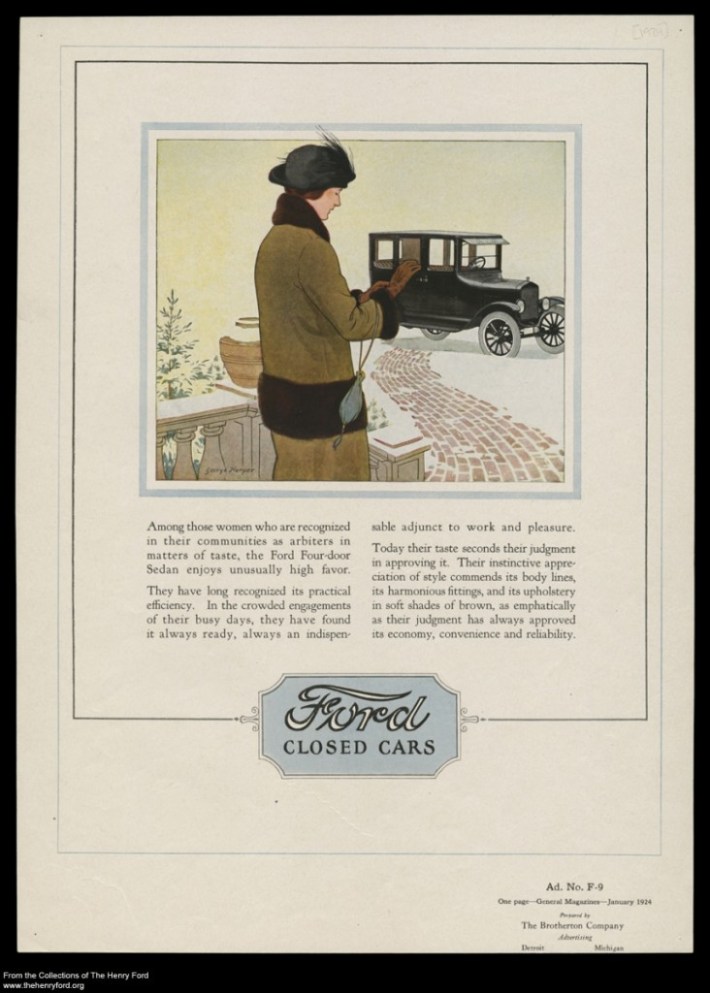

But by the time the Model T rolled around in 1908, gendered marketing was already starting to creep into the industry. Though Ford kept churning out text-heavy ads extolling the price and performance of their signature vehicle, it also launched their fashion- and comfort-focused "Closed Cars" campaign, designed to appeal to sexist assumptions about what women wanted: to be tasteful, comfortable, and have nice upholstery.

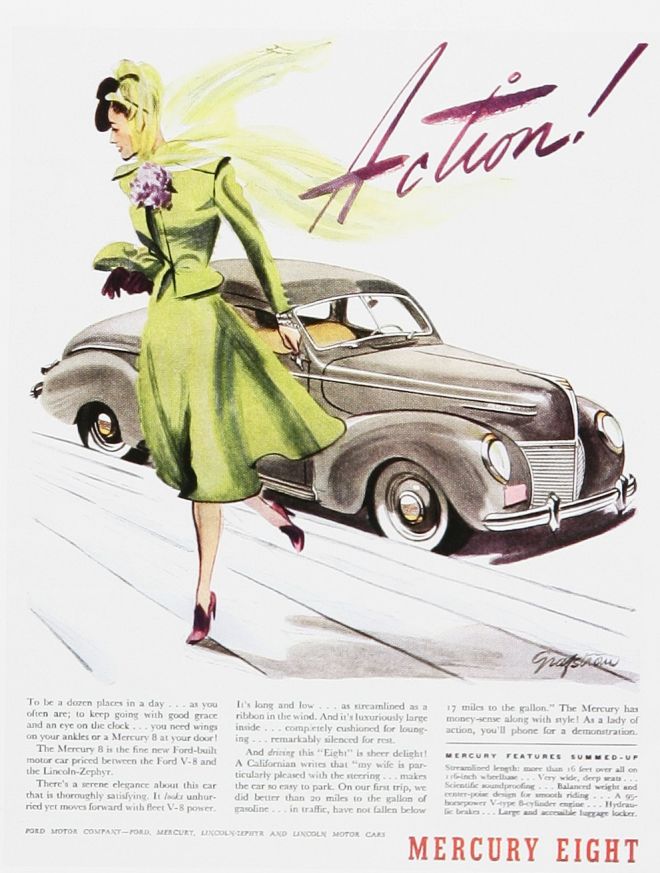

Women became even more central figures in automotive ads in the mid-century decades, but not exactly for enlightened reasons. Through the 1930s and '40s, the car was often marketed as a tool for busy housewives to stay flawlessly stylish and attractive while performing the household errands (read: unpaid domestic labor). Check out this one, which comes complete with a quote from a satisfied husband reporting how impressed his wife was with the new Mercury Eight he bought her.

Source: VintageCarAds

But don't worry, fellas — even though your wife is a silly woman who only cares about "gay colors" and "easy gear change" (what with her tiny, weak hands and all,) you're still the one buying it, so you can "insist" on something sensible, too. And even though you're a super-smart guy who will demand advanced safety features like brakes on your car, don't worry: it'll still be every bit fun to drive! (And, of course, men's appreciation for the, uh, "joy" of "handling" is well documented.)

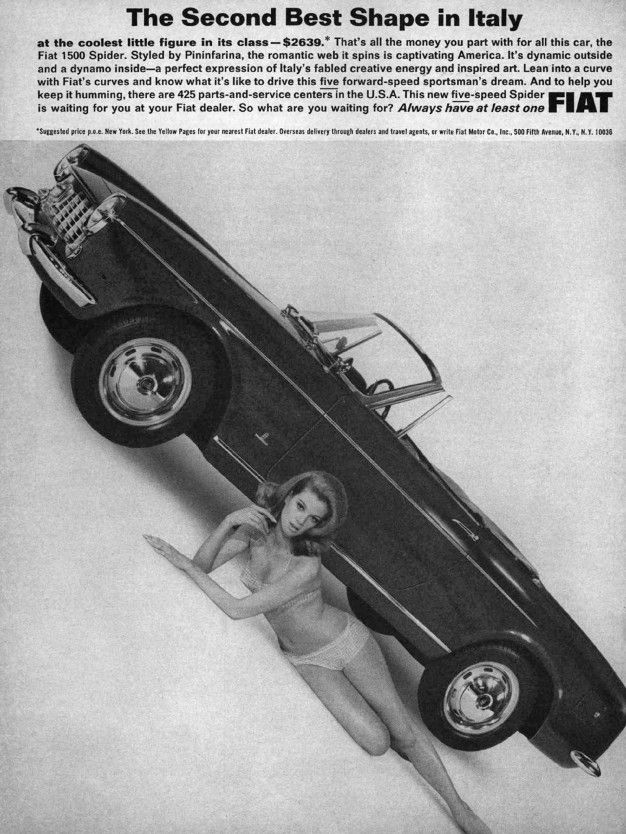

But with the rising popularity of NASCAR in the 1950s, the tone of car ads took a hard left turn away from the dependable family sedan and towards athletic performance and sleek individualism. The aspirationally gorgeous stay-at-home mom was suddenly forced out of the carpool-lane driver's seat — and she was replaced with ... this other aspirationally gorgeous lady taking a bikini nap on the garage floor for some reason!

If you're not familiar what types of "masculinity" qualify as "toxic," here's one easy example: defining a man's entire worth by his ability to have sex with lots and lots of women! Especially when the women's desires don't merit a mention, and are presumed to be so easily manipulated that the ladies will just go wild at the sight of...2,000 pounds of metal, or something.

By way of example, check out this gem:

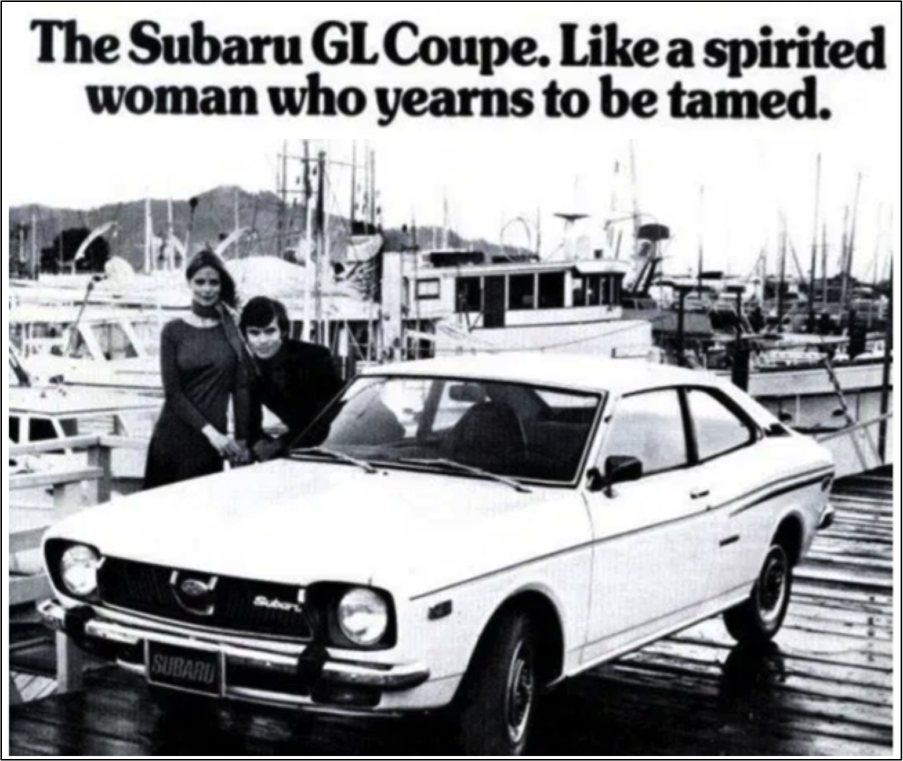

Sending them into inexplicable "cushy bucket-seat"-inspired sex frenzies isn't the only way that car ads suggest real men can and should control women.

Check out this 2017 commercial that treats marriage not as a mutual act undertaken among equals, but as something a man does to a woman when he chooses her for matrimony — y'know, sorta like when a discerning customer checks out all the tech specs on his new Audi before he writes a check at the dealership! (This one's from China, but it went viral in the U.S. — and not just among people who found it disgusting.)

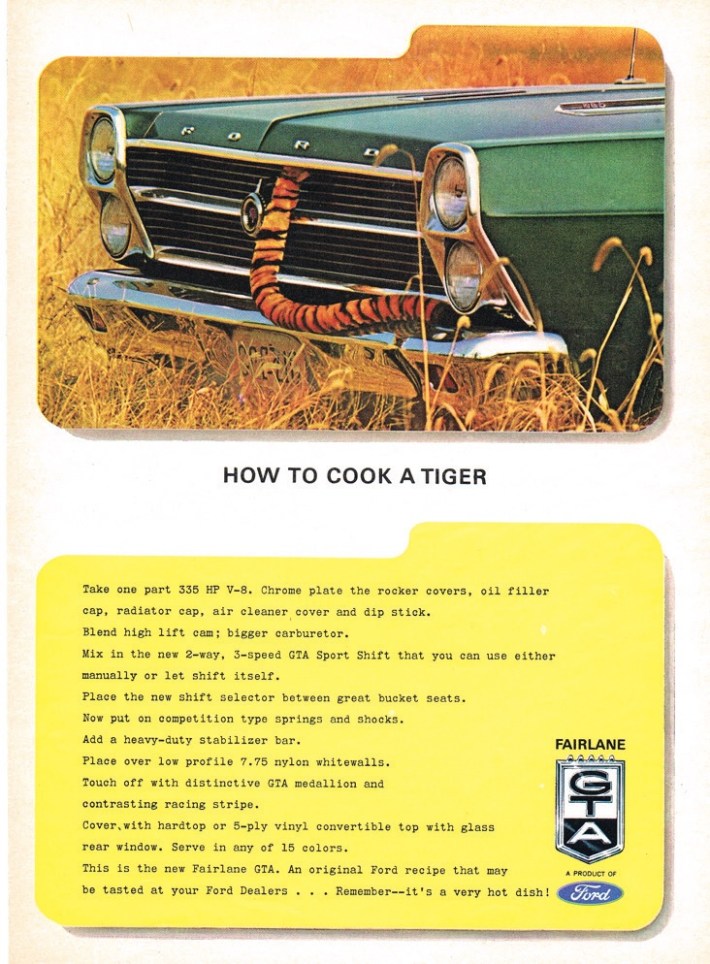

Another classic example of toxic masculinity: defining a man's worth by his ability to utterly dominate nature, regardless of how destructive it is to the ecosystem. See: this truly insane 1966 ad, for the man who just wants to run over an endangered species, scrape it off of his grill, and...eat it.

Of course, toxic masculinity isn't just about the domination of women and nature — it's also about the domination of other men. Here's a recent car ad featuring a male driver nearly running over a few dozen pedestrians and cyclists of all genders — because thats what cool and awesome men do, apparently?

(If you didn't notice it in that last one, by the way, the man isn't the only one enjoying the experience of ruling the road to the peril of all other road users: his girlfriend in the passenger seat is grinning, too. Women are just as susceptible to toxic masculine narratives about how to achieve power at the expense of others who are more vulnerable than them, even if there's a hard ceiling to how high toxic masculinity says women and femmes can climb.)

Car culture didn't create the toxic masculinity. But it's certainly used its worst tropes to its advantage from its start— and not just when it comes to car ads.

The rhetoric that lead to the approval of the Federal Highway Act was deeply infused with toxic masculine tropes of no-expenses-spared nationalism and the importance of achieving economic dominance over our foreign rivals. When auto industry groups lobbied for legal changes that favored drivers, they also "lobbied police to publicly shame transgressors by whistling or shouting at them — and even carrying women back to the sidewalk — instead of quietly reprimanding or fining them," according to Vox. Humiliation of a "lesser" person — much less bodily dominating her by carrying her out of the street against their will — is a hallmark of toxic masculinity, and car culture traffics heavily in aggressive displays of domination over other travel modes. (More on that in the next Streetsblog 101.)

And when we really think about it, the toxic masculine history of car shouldn't surprise us — because it's our present, too. Motorized vehicles, by definition, are dominant, violent, environment-destroying machines — yes, even the electric ones. If we want to introduce healthy masculinity into our culture more broadly — one based on strength, not force, and interdependence, not dominance — we may need to find another way to get around.