One of the few congressional proposals with bipartisan support even in these divisive times is a $287-billion transportation bill. But one possible funding stream — hiking the gas tax — remains up for debate.

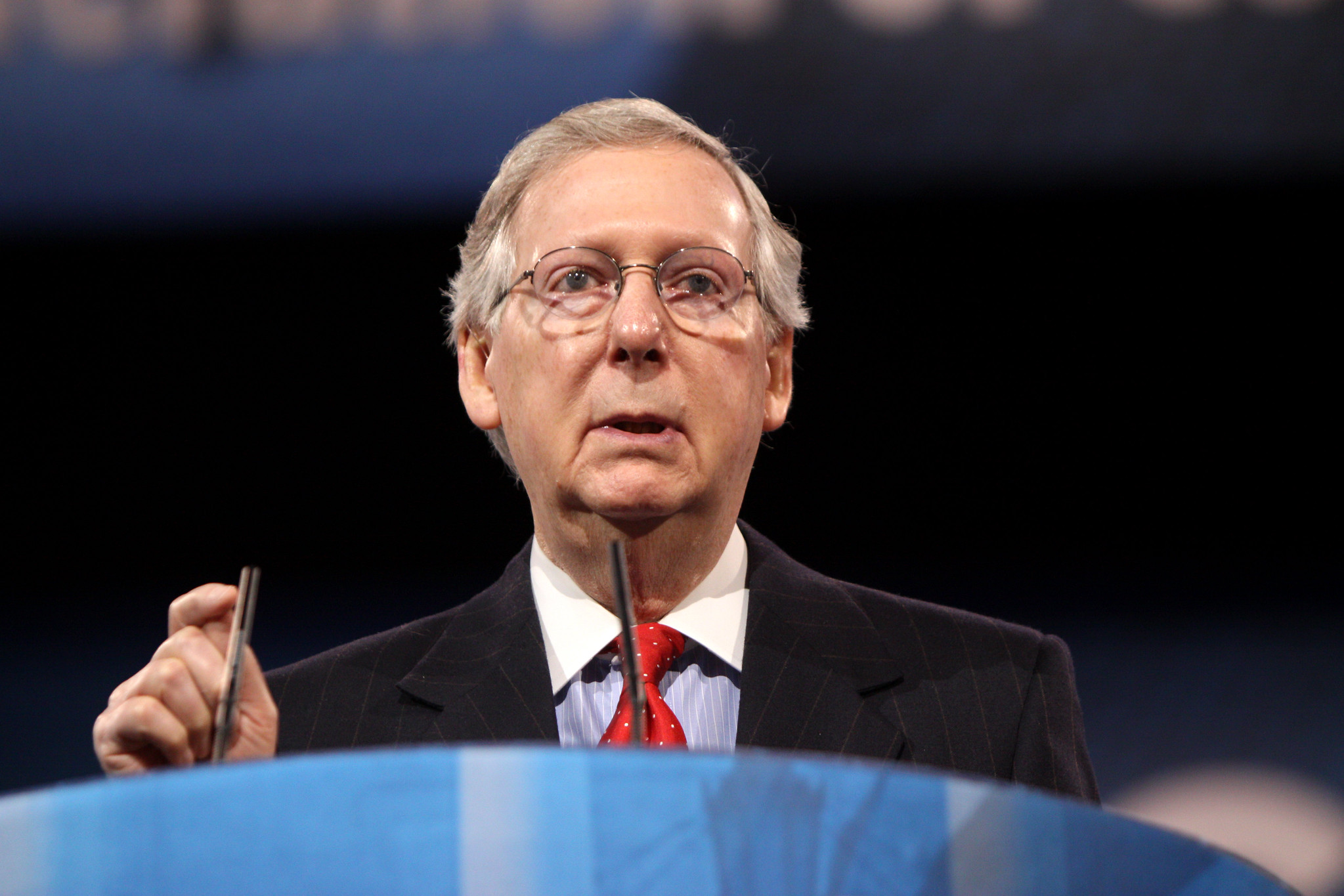

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell has already signaled that he will oppose significantly altering the gas tax, which is currently 18.3 cents per gallon. Some members of Congress are pushing for it to increase by 5 cents a year for five years.

"We’re going to do a transportation bill," McConnell told CNBC last week. "It probably won’t be as bold as the president was talking about, because if it were that bold, [it would] involve a whopping gasoline tax increase, which is very regressive, it hits medium- and low-income people very hard."

McConnell isn't wrong that a surcharge would hurt low- and middle-income drivers more than the wealthy, but raising the gas tax is good public policy for reasons that outweigh any short-term pain. Here are the four main reasons why raising the gas tax is good policy (and why Mitch is wrong).

Break car dependency

Americans have been addicted to their gas-powered vehicles for nearly a century, thanks to cheap gas prices, sprawling housing development, and an expansive interstate highway system that encourages drivers to rev up their cars for every possible errand. And they have — 87 percent of Americans use their cars to make daily trips, 45 percent of which are for shopping and other errands and 27 percent are for social and recreational reasons, according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Government subsidies have also helped keep the costs of owning a car low. Vehicle registration fees, tolling, and gas surcharges make up between 60 and 70 percent of the amount covering roadway expenditures while the rest is covered by other taxes that have nothing to do with transportation. Drivers in Europe pay three to four times more than Americans do per year in tolls, taxes, and other fees — with Europe's high gas tax a significant portion of that.

"We’re usually envious of transportation abroad of its quality and condition and those other countries have much higher fuel taxes, dollars per gallon rather than cents per gallon," said Eno Center Policy Director Paul Lewis. A tiny increase probably won't change driver behavior, but raising fuel taxes to levels comparable to our European counterparts would make American drivers think twice about using their cars as much as they do — especially now that owning a car is increasingly becoming unaffordable for middle-class families.

That should mean more trips on transit when the option is available.

Shift shipping to freight

A "whopping" gas tax hike wouldn't just affect private car owners, but would also add costs to the freight industry, which relies on trucks to move goods across the country. Truck transportation volume rose by 4.2 percent in 2018, thanks to a healthy economy and an uptick in consumer demand through e-commerce, but freight costs have also been rising.

The American Trucking Association has been advocating for a 20-cent per gallon increase in fuel levies, which truckers would presumably pass along to customers, as long as highway tolls remained flat. But McConnell and other lawmakers are likely worried that sharply increasing gas taxes on top of tolls might result in protests resembling the yellow-vest demonstrations that paralyzed France last year.

But shipping companies might shift their freight from trucks to more sustainable, less-pollution rail systems if the costs to ship goods across highways rise. Gas tax revenue that could go toward improving and expanding the country's rail networks could further encourage this trend.

Reduce emissions and reliance on oil

A fuel surcharge that results in less driving would correspondingly lower the amount of pollutants vehicles spew into the atmosphere. The transportation sector contributes 29 percent of greenhouse gas emissions in America, surpassing power plants as the largest source of carbon dioxide, according to the EPA. So it makes sense to look at a fuel levy as a tax on energy consumption that could incentivize drivers to change behaviors.

A 10-cent-per-gallon increase in the gas tax, for instance, could result in a 1.5-percent reduction in carbon emissions from vehicles in the United States, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research study. Better car emissions standards would certainly help, too, despite what the Trump administration says, but the bigger problem has been that people are buying more cars and driving them more often, counteracting those efforts.

A combination of a higher gas tax, stricter emissions standards, and using tax revenue to incentivize cleaner transportation should be pursued.

Better transit

McConnell and other legislative leaders like to spend money on projects for their constituents so they can cut a ribbon in their districts. You can't cut a ribbon on a tariff, but you can cut ribbon on a new train station. Look at the Republican lawmakers embracing a Gulf Coast Amtrak line as well as rail projects in Florida and Texas.

A larger share of the gas tax revenue could be diverted from road maintenance to funding transit, which could wean drivers from their vehicles. But that's not likely within the current car culture. The existing gas tax is expected to raise $41 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office, but the government is poised to spend $58 billion on highway and transit spending — meaning a shortfall of $17 billion.

Drivers are not likely to be keen on their elected officials using a higher percentage of gas tax revenues for transit because, well, America.

"I think transportation would [opinion poll] really well if it weren’t tied to fuel taxes," Lewis said. "In other countries, higher spending on transportation spending is popular. We’ve set an artificial limit based on the fact we can’t increase the fuel tax, and that’s hamstrung us to fund transportation at the levels we want."

This issue goes beyond a mere hike in the gas tax to a larger debate over transit funding in general, Lewis added.

Europe, he said, "views fuel taxes not as a user fee like we do here but as a carbon tax to reduce fuel they use — and all that revenue goes into general fund, not earmarked for transportation [whether highway building or transit funding]. Without fuel-tax-based funding, there’s no fight over what mode gets to benefit from it. It’s not so modal like it is here.

It's a complex problem, but essentially with higher fuel taxes divorced from transit funding, European countries can fund transit at levels they want, he concluded.