All the Bad Things About Uber and Lyft In One Simple List

12:32 PM EST on February 4, 2019

Photo: Oran Viriyincy/Flickr

Here's the latest evidence that Uber and Lyft are destroying our world: Students at the University of California Los Angeles are taking an astonishing 11,000 app-based taxi trips every week that begin and end within the boundaries of the campus.

The report in the Daily Bruin revealed anew that Uber, Lyft, Via and the like are massively increasing car trips in many of the most walkable and transit friendly places in U.S.

It comes after a raft of recent studies have found negative effects from Uber and Lyft, such as increased congestion, higher traffic fatalities, huge declines in transit ridership and other negative impacts. It's becoming more and more clear that Uber and Lyft having some pretty pernicious effects on public health and the environment, especially in some of the country's largest cities.

We decided to compile it all into a comprehensive list, and well, you judge for yourself. Here we go:

They increase driving — a lot

The U.C.L.A. trips are an example of what is happening at a much wider scale: A lot more driving.

Uber and Lyft, for example, are providing 90,000 rides a day in Seattle now. That's more than are carried daily by the city's light rail system, the Seattle Times reports.

One study estimated that in cities with the highest Uber and Lyft adoption rates, driving has increased about 3 percent compared to the cities with the lowest. That's an enormous amount of miles.

And transportation consultant Bruce Schaller estimates that the app-based taxis have added 5.7 billion driving miles in the nine major cities they primarily operate. (For comparison, in their first year of deployment across the U.S., e-scooters operated by private tech firms carried between 60-80 million trips.)

By the end of this year, Schaller has estimated all taxi ridership will surpass the number of trips made on buses the U.S.

The promise of companies such as Uber and Lyft was that they would "free" city dwellers to sell their cars or not acquire them in the first place. And car ownership has declined among higher wage earners.

But a University of Chicago study found the presence of Uber and Lyft in cities actually increases new vehicle registrations. That's because the companies encourage lower-income people to purchase cars, even advertising in some markets how people should put that new car to use — as an Uber.

They spend half their time 'deadheading'

For every mile a Uber or Lyft car drives with a passenger, it cruises as many miles — if not more — without a passenger, a practice known in the industry as "deadheading." Estimates of total deadheading time vary from 30 percent to as much as 60 percent.

Uber and Lyft's policies make this worse by encouraging drivers to constantly circle to reduce wait times for users, according to John Barrios, the researcher at the University of Chicago, who has studied Uber and Lyft.

They operate in transit-friendly areas

Transit systems around the nation are losing riders to Uber and Lyft, which suggests that the companies are merely showing the need to beef up transit service across the country.

But if you drill down, something else is at work because Uber and Lyft primarily operate in areas that are best served by transit. For example in Seattle, about half the rides taken in Uber and Lyft originate in just four neighborhoods: downtown, Belltown, South Lake Union and Capitol Hill, according to David Gutman at the Seattle Times. These are some of the city's most walkable and transit-friendly areas.

Moreover, according to Schaller, about 70 percent of Uber and Lyft trips take place in just nine American cities: Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington, D.C.

Meanwhile, traditional taxi service, Schaller estimates, still serves more total trips in suburban and rural areas than the Ubers and Lyfts.

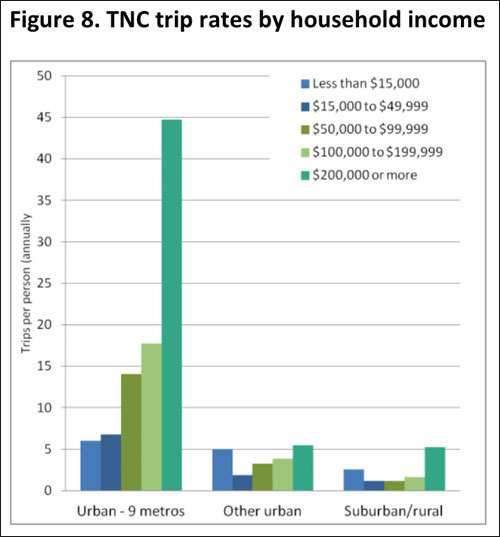

Why would Uber and Lyft use be so high in dense, transit-rich areas? Studies aren't conclusive, but on average, Uber and Lyft riders, not surprisingly, skew rich and skew young.

In the top nine cities for Uber and Lyft people with incomes above $200,000 are by far the most likely to use the service. Lower-income people without cars in some less urban markets do use Uber and Lyft, but their use is dwarfed by those with high incomes, Schaller finds.

They mostly replace biking, walking or transit trips

In an ideal world, Uber and Lyft would be making good on their promise to reduce private car ownership because city dwellers would feel more comfortable selling their cars, thanks to the presence of Uber and Lyft.

But the data shows that Uber and Lyft mostly "free" people from walking and transit.

A survey of 944 Uber and Lyft riders by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council in Boston last year, found that 42 percent of riders would have taken transit if the services hadn't been available. Another 12 percent (like those U.C.L.A students and their 11,000 on-campus taxi rides per week) said they would have biked or walked their journey. Another 5 percent would have just avoided the trip altogether.

Only about 17 percent — less than one in five — said they would have made the journey in a private car otherwise. (The remainder said they would have used a traditional taxi.)

Uber and Lyft just aren't competitive price-wise with private car ownership, Schaller said, except in areas with expensive parking. Even with Uberpool and other shared services — which account for a small share of total business, Schaller says — Uber and Lyft increase car miles on urban streets. For each mile of driving removed, they add about 2.6 miles, he estimates.

They hurt transit

Uber and Lyft are just crushing transit service in the U.S. A recent study estimated, for example, they had reduced bus ridership in San Francisco, for example, 12 percent since 2010 — or about 1.7 percent annually. And each year the services are offered, the effect grows, researcher Gregory Erhardt found.

Every person lured from a bus or a train into a Lyft or Uber adds congestion to the streets and emissions to the air. Even in cities that have made tremendous investments in transit — like Seattle which is investing another $50 billion in light rail — Uber and Lyft ridership recently surpassed light rail ridership.

Transit agencies simply cannot complete with private chauffeur service which is subsidized at below real costs by venture capitalists. And maybe that's the point.

Erhardt, for example, estimated that San Francisco would have had to increase transit service 25 percent overall just to neutralize the effect of Uber and Lyft.

Worse is the tale of two cities effect: Relatively well off people in Ubers congesting the streets of Manhattan and San Francisco slow down buses full of relatively low-income people. By giving people who can afford it escape from the subway, Uber and Lyft also reduce social interaction between people of different classes and lead to a more stratified society.

They reduce political support for transit

As an added kick in the shins, Uber and Lyft degrade political support for transit. If relatively well-to-do people can hop in an Uber or a Lyft every time the bus or train is late, the political imperative to address the problem is reduced. The wealthier people substituting Uber and Lyft for transit trips have disproportionate political influence.

Cities are already capitulating. Last week, Denver partnered with Uber in a last-ditch effort to win back some riders who had jumped to the app.

In addition, right-wing ideologues have argued that Uber and Lyft make transit investment unnecessary.

They increase traffic fatalities

The University of Chicago study mentioned earlier estimated that Uber and Lyft increased traffic fatalities last year by an astonishing 1,100 — an enormous human toll. The study also found, surprisingly, that Uber and Lyft have no effect on drunk driving.

In addition, Uber and Lyft require basically no safety training for their drivers at all. In fact, the presence of these companies has motivated cities like Toronto to eliminate safety training requirements the city previous required for taxi drivers, in order to ostensibly level the playing field.

They hoard their data

One qualification with this list: Much of the information we have about Lyft and Uber is imperfect. The two companies make it difficult to study the social impacts of their activities because they jealously guard their data.

Last year, when Barrios released a study showing a lot of negative impacts from Uber and Lyft, Lyft corporate attacked the study calling it “deeply flawed.”

But Barrios had to use Google search numbers to estimate Uber and Lyft penetration in certain markets because even academic researchers don't have access to Uber and Lyft's raw trip data. If Uber and Lyft are honest in their denials, releasing their data could help disprove it. But so far, they have mostly refused.

Oh, and one more thing...

These are just the transportation related drawbacks. To say nothing of these companies treatment of their employees, or the behavior of their top management or their huge financial losses.

Angie Schmitt is the author of Right of Way: Race, Class and the Silent Epidemic of Pedestrian Deaths in America, and the former editor of Streetsblog USA.

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Streetsblog USA

Kiss Wednesday’s Headlines on the Bus

Bus-only lanes result in faster service that saves transit agencies money and helps riders get to work faster.

Freeway Drivers Keep Slamming into Bridge Railing in L.A.’s Griffith Park

Drivers keep smashing the Riverside Drive Bridge railing - plus a few other Griffith Park bike/walk updates.

Four Things to Know About the Historic Automatic Emergency Braking Rule

The new automatic emergency braking rule is an important step forward for road safety — but don't expect it to save many lives on its own.

Who’s to Blame for Tuesday’s Headlines?

Are the people in this photo inherently "vulnerable", or is this car just dangerous?