The best way to ensure that congestion pricing doesn't hurt the poor is to make sure revenues from new tolls support better transit service — not just build more highways.

That's a key finding of a new report [PDF] by TransForm, a sustainable transportation advocacy group in California that sees congestion pricing as a way of advancing transportation equity — but only if the plan makes buses move faster, improves air quality and improves transit.

It's not a given though; for congestion pricing to be fair depends on how it's structured.

Congestion pricing — currently in use in London and many European cities — reduces driving by 15 to 20 percent, and congestion by 30 percent, TransForm says. A lot of cities want those benefits.

In cities such as Seattle, Los Angeles, New York and Portland, where congestion pricing is being discussed, local politicians instinctively question the new tolling policy as a tax on lower-income drivers. In fact, the majority of rush-hour commuters who drive into the central business district of major cities — especially in New York — are wealthier than their transit-bound neighbors. Transportation is inequitable in myriad ways both invisible and visible, thanks to the dominance of the automobile, the starving of public transit and the lack of affordable housing in our gentrifying city centers.

That's why it's crucial to design a truly progressive congestion pricing program, says TransForm.

"When implemented without a clear focus on social and racial equity, road pricing programs can burden low-income drivers with new costs and deepen existing inequities," the group writes. "But when equity concerns and deep community engagement help shape road pricing programs and their reinvestment strategies, they can lead to more frequent and affordable public transit, safer pedestrian and bicycle routes, and improved health outcomes for vulnerable communities — all important components of an equitable transportation system."

Here's what the group recommends:

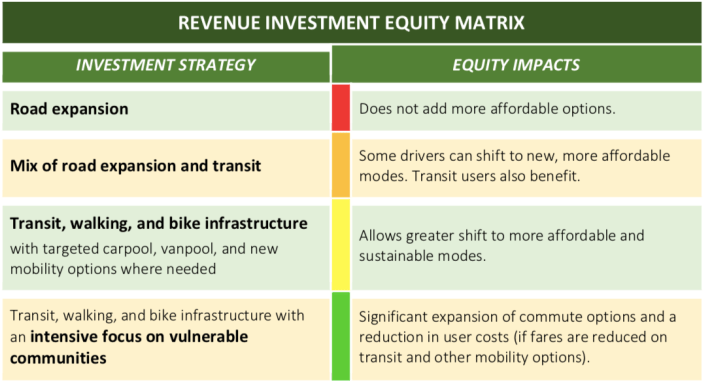

#1. Use revenues to fund alternatives

High housing costs push the middle class and the poor away from job centers. If cities don't have good transit, those workers will likely drive, which means congestion pricing would saddle them with higher transportation costs. But if the money is used for transit or alternative modes of transportation, the middle class will benefit at the expense of drivers, who tend to be wealthier.

And using congestion pricing to fund transit is a win-win: it's also better for the environment — and environmental equity has long eluded low-income groups and people of color.

"Road pricing is a necessary step to building a healthier and more efficient transportation system, but it has to be done in a fair way," said Hana Creger, environmental equity program manager at the Greenlining Institute, a racial policy shop in Oakland. "The needs of vulnerable populations [should be] first and foremost at the conversation."

Many cities — Los Angeles, New York and Minneapolis included — already dedicate a portion of their highway toll revenue to transit.

Congestion pricing can help advance transportation equity outcomes in and of itself. TransForm writes that when London set up its pricing ring, bus wait times dropped 30 percent and delays due to congestion were reduced by 60 percent.

#2. Free or discounted alternatives

In addition to discounts or exemptions, or as an alternative, cities may want to consider offering discounted transit fares in response to congestion pricing. Many cities — Seattle, Denver, New York — already offer discounted transit fares to low-income people. And many other cities — Chicago, Boston, New York — also offer discounted bike share passes to low-income residents.

#3. Subsidies, discounts, caps and exemptions

Some cities are considering programs that would give discounts to low-income drivers or small business owners for their trips into the congestion pricing zone.

London, for example, exempts people with disabilities and their drivers from the charges through its "Blue Badges" program. The city also discounts tolls for people who live within the congestion pricing area by 90 percent. And Seattle is considering income-based discounts on a tiered scale, so those making $25,000 or less would pay the lowest toll.

Such income, disability or residency status discounts can help build political support for congestion pricing. But they "need to be carefully weighed against other program goals such as moving traffic more efficiently or reducing greenhouse gas emissions," TransForm notes.

Discounts can also undermine the central goal of congestion pricing: reducing car travel.