Originally published by Carbon Tax Center.

Before you take umbrage at the headline, let me be clear: President Trump’s decision last week to freeze federal car-mileage standards at 2020 levels and revoking California’s authority to set the nation’s pace on auto emissions and fuel efficiency is contemptible.

The MPG freeze means more carbon emissions hastening the plunge into climate chaos not only for Americans but for the seven-plus billion other people with whom we share the planet. The California revocation also brings the curtain down on that state’s half-a-century of innovation in low-emissions regulation and technology.

Both moves are archetypal Trumpian policy-by-pique. Their sole purpose is to stick mud in the eyes of Gov. Jerry Brown, who with his father, Gov. Pat Brown, pioneered green state governance; of President Obama, for whom ramping up auto MPG requirements was a cornerstone measure to combat global warming; and of untold numbers of Americans who care deeply for our environment.

The policy, a gift to oil companies, accomplishes nothing while sowing vast damage. Like Trump himself, it is spiteful, sickening and stupid.

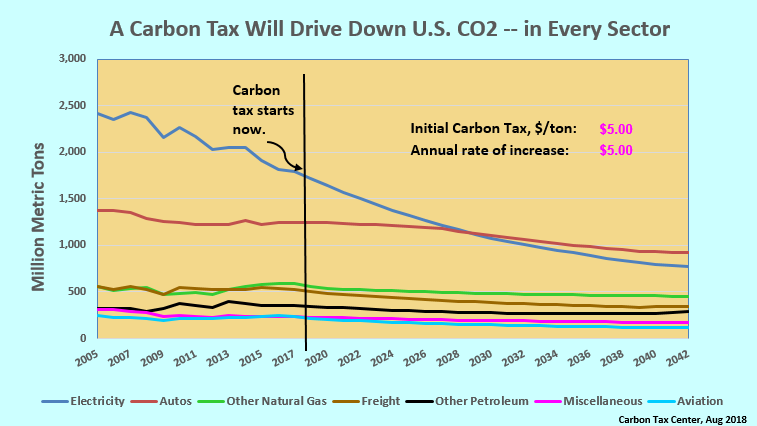

Emission trajectories shown reflect carbon tax that would diminish CO2 from autos as much as Trump’s MPG freeze will raise them. Economy-wide decreases in analysis-year 2035 are eight times as great as auto impacts alone.

But what’s also true is that a mid-range carbon tax could recoup the lost ground. I calculate that a U.S. carbon tax that started next year at a level of $5 per ton of carbon dioxide and increased by $5 a ton each year, with no letup, would, by 2035, be curbing carbon emissions from gasoline use by the same amount that Trump’s cessation of tighter MPG standards will increase them — around 140 million metric tons of CO2 a year.

Moreover, such an economy-wide carbon tax would bring about parallel drops in emissions throughout the economy — in electricity generation, freight-hauling, aviation and industry. I estimate that in 2035, when the hypothetical carbon tax would have reached $85 per ton, those reductions would amount to an additional 980 million metric tons. All told, the carbon tax would suppress carbon dioxide emissions eight times as much as the mileage freeze will elevate them.

To reflect the hypothetical nature of the carbon tax I express its benefits in the subjunctive (“would”) while employing the definite tense (“will”) for the Trump rollbacks. This is a necessary concession to the arduous and uncertain task of passing a U.S. carbon tax, in contrast to the president’s all-too-real administrative powers — notwithstanding the fierce legal and political challenges that will be mounted against both moves. The point is not to trivialize the White House’s latest destructive act but to highlight the vast potential of a robust carbon tax to cut emissions.

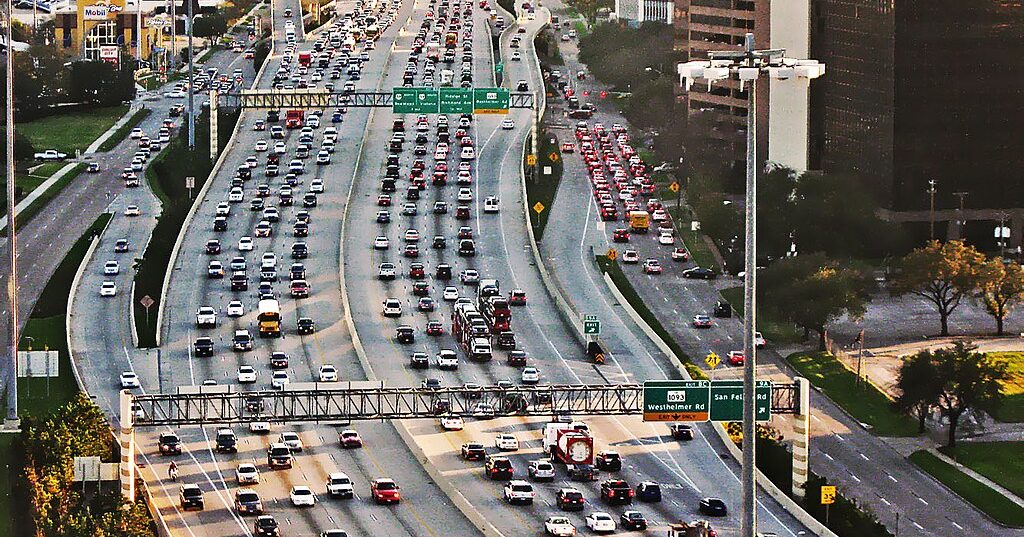

A carbon tax covering gasoline would stand in for higher MPG standards, in part, by nudging consumers to more fuel-efficient vehicles and, thus, incentivizing manufacturers to design and market them. More than that, the higher fuel price could inflect drivers’ day-to-day decisions on how far to travel and, for multi-car families, which car to take, not to mention how aggressively to drive. Vehicle miles traveled (VMT) would shrink somewhat as well, as decision-needles tilt toward car-sharing, trip-chaining, public transit, and walking and biking.

This isn’t to overstate the link between higher fuel prices and lower gasoline use. In our modeling at the Carbon Tax Center we employ a “long-run” gasoline price-elasticity of just 0.35 (discussed and derived here), by which prices at the pump must rise by a third to cut usage by a tenth. It also bears repeating that not all Americans have agency to respond to price rises. But while a binary frame may be useful for viewing individuals’ fuel-use decisions, the aggregate level of fuel use (and the resulting carbon emissions) is the product of literally billions of daily and longer-term decisions.

Moreover, autos (cars and light trucks) make up just one-quarter of U.S. carbon emissions — even when “upstream” oil refining is factored in. The sectors yielding the other three-quarters of U.S. CO2 — electricity, freight, air travel, industry, heating, construction — are more price-elastic, which is why a carbon tax that would recoup the reductions from the higher MPG standards would yield another 7-fold’s worth of reductions.

So yes, Bill McKibben is spot-on to call the mileage freeze Trump’s “stupidest decision yet in his endless attempt to roll back environmental protections.” And yes, a carbon tax of any stripe, let alone one that could rise to $85 per ton by 2035 as in our modeling exercise here, remains nowhere in sight so long as Republican extractionism and malice rule Congress and the White House.

But that’s not cause to ignore or abandon the long-term campaign for a robust U.S. carbon tax. Quite the opposite.

The Numbers Explained: We used the Rhodium Group’s May 2018 analysis, Sizing Up a Potential Fuel Economy Standards Freeze. For 2035, Rhodium projected a 114 million metric ton fallback in CO2 reductions if oil prices are low, and 32 million tons if prices are high. (The high-price fallback projection is smaller because expensive gasoline would do some of the work of MPG standards in engendering fuel efficiency while also dampening the amount of driving.) We conservatively used the higher figure and added 20 to 25 percent to capture upstream (refinery) emissions, yielding a target of 140 million metric tons. Through trial-and-error, we found that CTC’s carbon-tax model (downloadable as an Excel spreadsheeet) also projects a 140 million metric ton reduction from gasoline use, with a hypothetical carbon tax that would start next year at $5/ton and rise by $5/ton annually, in constant-2017 dollars. The economy-wide (all sectors) reduction is 1,122 million metric tons.