Cities and states all over the country have adopted "complete streets" policies that say walking, biking, and transit -- not just driving -- need to be considered in street design and transportation policy. But changing the entrenched practices of transportation agencies is easier said than done.

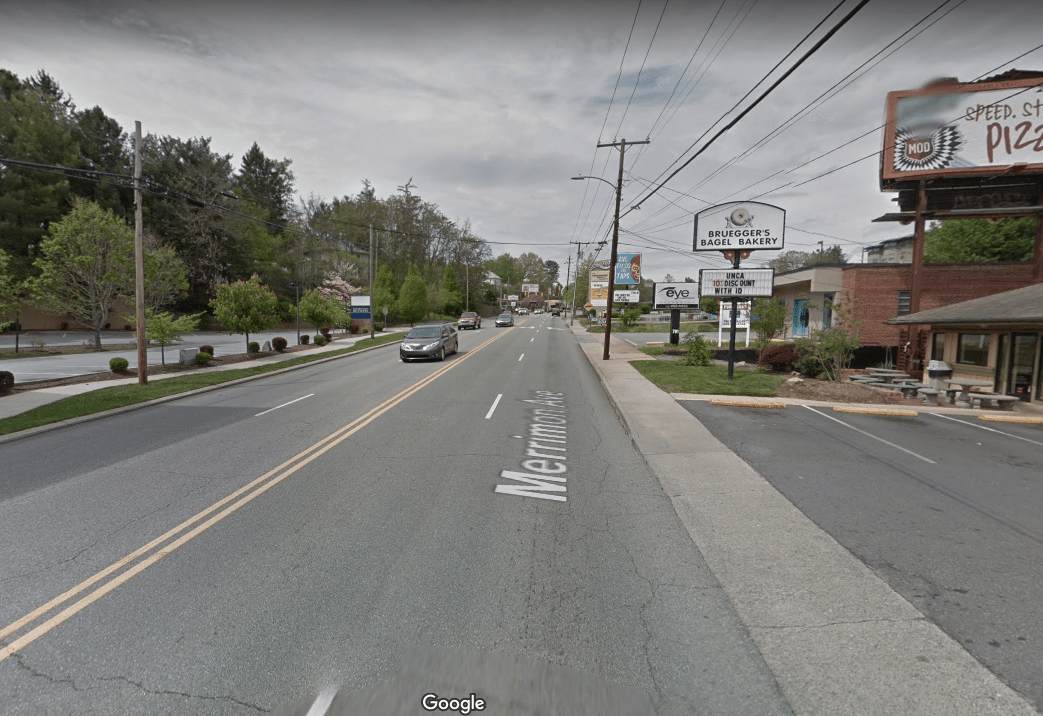

In North Carolina, where the state DOT adopted a complete streets policy in 2009, it can be difficult to discern any actual improvement in practice. Residents of Asheville, for instance, are in the midst of fending off car-centric NC DOT projects like the widening of Merrimon Avenue and the I-26 Connector.

To his credit, DOT Secretary James Trogdon has acknowledged the disconnect. He recently commissioned an outside consultant to evaluate how well the agency is implementing its complete streets policy.

In a report released earlier this month, WSP USA (formerly known as Parsons Brinckerhoff) substantiated concerns that NC DOT has not made the transition to multi-modal transportation planning [PDF]. Cars still come first.

The good news is that people who work at the agency recognize the problem and have thought about how to fix it. In 45 interviews with NC DOT staff, municipal workers, regional planning agencies, and biking and walking advocacy organizations, WSP identified these four barriers to complete streets.

1. Bias in project selection

One of the big obstacles, interviewees said, is NC DOT's project scoring method. The formulas that determine which projects the agency builds remain stacked against complete streets. A project with walking and biking infrastructure "may score higher on safety criteria, but the project will have lower scores on cost-benefit and congestion, which brings its overall score down."

In addition, the state requires cities and towns to share the costs of features outside the curb -- namely sidewalks -- which can be prohibitively expensive for some municipalities.

2. No accountability

There is no person or division inside NC DOT with clear responsibility for implementing or coordinating complete streets. Without dedicated staff, improvements for walking and biking can get lost in the shuffle, interviewees said.

3. Institutional inertia

Historically, NC DOT is a highway department, and the institutional culture remains embedded in the highway era. (The branch of the agency devoted to road projects is still called the Division of Highways.) Changing agency culture to adopt a truly multi-modal perspective has not come easily.

"It is important for NCDOT to have a paradigm shift," WSP wrote, saying the agency needs to turn away from an "auto-centric focus." The report recommends adopting new metrics to gauge success that focus on the convenience and safety of walking and biking. (More detailed recommendations are expected in a follow-up report.)

4. Outdated design guidelines

Complete Streets guidelines have not been incorporated into the design manuals used by NC DOT engineers. The existing guidelines still emphasize auto travel, not walking, biking, or transit. The engineers rely heavily on the AASHTO design manual or “Green Book,” which has been notoriously sluggish to incorporate design templates like protected bike lanes.