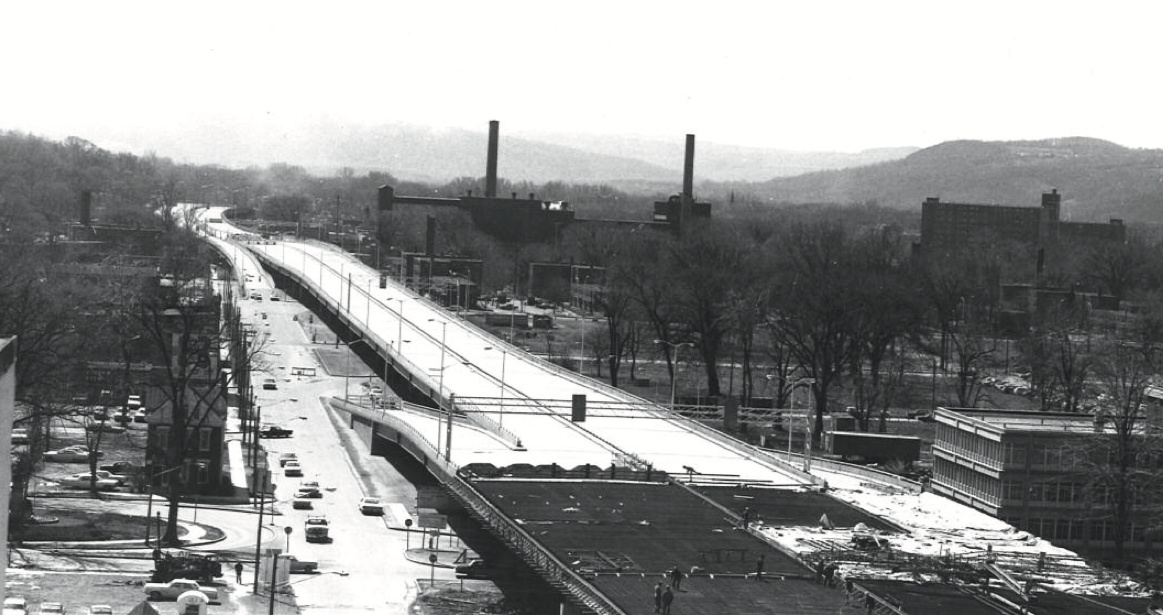

When Interstate 81 was constructed in the 1960s, the elevated highway sliced through Syracuse's 15th Ward, decimating a thriving black neighborhood. To this day, the highway is a blight on Syracuse, and the 15th Ward has never been the same.

Syracuse is more segregated than most American cities, with some of the largest clusters of extreme poverty anywhere in the nation. Former City Council president Van Robinson has likened I-81 to the Berlin Wall, dividing the city between "the haves and the haves not."

But like the Berlin Wall, this highway might come down. New York State is seriously considering a plan to remove the 1.4-mile stretch of I-81 in downtown Syracuse and replace it with a local street grid. The teardown is one of three options the state is now considering, along with rebuilding the viaduct and constructing a (very expensive) sunken highway.

The teardown of I-81 presents an opportunity to rebuild Syracuse in a way that rights past injustices, says Anthony Armstrong of the planning firm Make Communities. Removing the highway is still far from assured, but if New York Governor Andrew Cuomo does go through with it, Syracuse could make serious progress reversing the city's history of segregation.

In a new report funded by the Poverty & Race Research Action Council, Armstrong proposes analyzing the I-81 project not through the traffic engineer's lens of moving traffic, but through an "Equity Impact Statement" that seeks out opportunities to lessen segregation and redress social inequities [PDF].

The idea is to transpose the Environmental Impact Statement process to a different goal: ensuring that people who've been marginalized by past planning efforts benefit from new initiatives. The model has been applied to school planning in Boston and Minneapolis, and by the Obama administration in its Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing initiative. As part of that effort, HUD, U.S. DOT, and the Department of Education developed programs that jointly addressed segregation in housing, transportation, and education.

For a project like the I-81 teardown, which would open up new land for development and create new street connections between neighborhoods, the analysis would look for opportunities to ensure benefits accrue to residents who had been harmed by the highway and the segregation it exacerbated.

Construction jobs and new housing could be set aside for black and Latino residents who have historically been excluded from opportunity, for instance. The enrollment area of schools in the area -- there's one right by the highway -- could be redrawn to reduce racial inequities.

Armstrong said it's too early to recommend specific policies. "It’s difficult if not impossible to impose discrete solutions from the outside on a project like this," he said. But the I-81 project could be a springboard for formulating policy related to housing, education, and economic development.

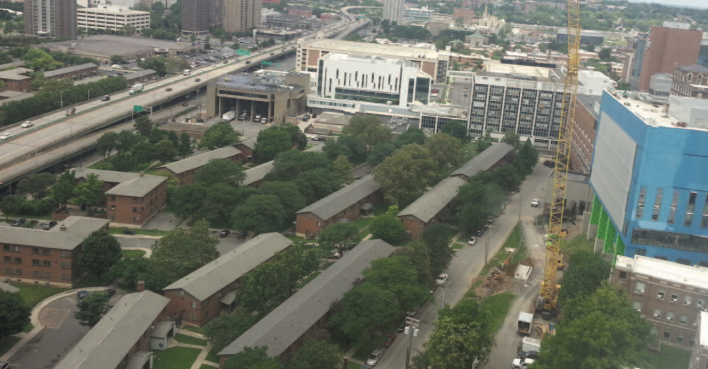

Currently, about 1,300 people live in the Pioneer Homes -- low-rise public housing just west of the highway. The buildings are aging and in need of major repairs, and the Syracuse Housing Authority has developed a plan to replace the low-rise housing with mixed-income, mixed-use housing at higher density.

The removal of I-81 would present an opportunity to make the neighborhood more economically integrated and offer better access to opportunity, but also introduces the risk of displacement. Without the highway in place, unsubsidized housing construction becomes more feasible. The Equity Impact Statement process would assess how to maximize benefits and minimize adverse impacts for current residents of Pioneer Homes.

It's a very different way of thinking about transportation projects than just crunching the numbers about motor vehicle delay. "DOT is so often focused on that level of service to the exclusion of all else," said Armstrong. "It’s really shifting that paradigm of how that process is conceptualized and designed."