When a bike path is added to a highway expansion project, it risks being an afterthought, resulting in a low-quality, high-stress route. Riders, inundated with noise and pollution from cars, end up not using the path. Northern Virginia bicycle advocates fear that could happen to a planned bike path along Interstate 66 in Fairfax County -- and they're asking the state department of transportation to come up with a better design.

In recent years, Virginia has undergone a highway building boom, not by building new expressways but by contracting with private companies to add high-occupancy toll, or HOT, lanes. The latest plan is to add four new toll lanes -- two in each direction -- to more than 20 miles of I-66 beyond the Capital Beltway, widening the highway from three lanes in each direction to five.

Many transportation advocates opposed the project, pointing out the folly of expanding highways to cure congestion. Nevertheless, last November Governor Terry McAuliffe awarded a 50-year contract to a private consortium to build it. Before the contract went out to bid, advocates succeeded in getting the state to include a multi-use path and better bus service as part of the deal.

A bike path already exists along much of I-66 inside the Beltway, and the bike path along the wider section of I-66 would connect to Metro stations while getting riders close to Tysons Corner and other job centers. It would also connect with the Cross County Trail and pass near the Washington & Old Dominion Trail, a popular rail-trail across Arlington and Fairfax counties.

“A quarter of the population of Fairfax lives within a mile of this corridor. We ought to be serving them,” says Jeff Anderson, president of the Fairfax Alliance for Better Bicycling, or FABB. "It's being shoehorned in because we asked for it."

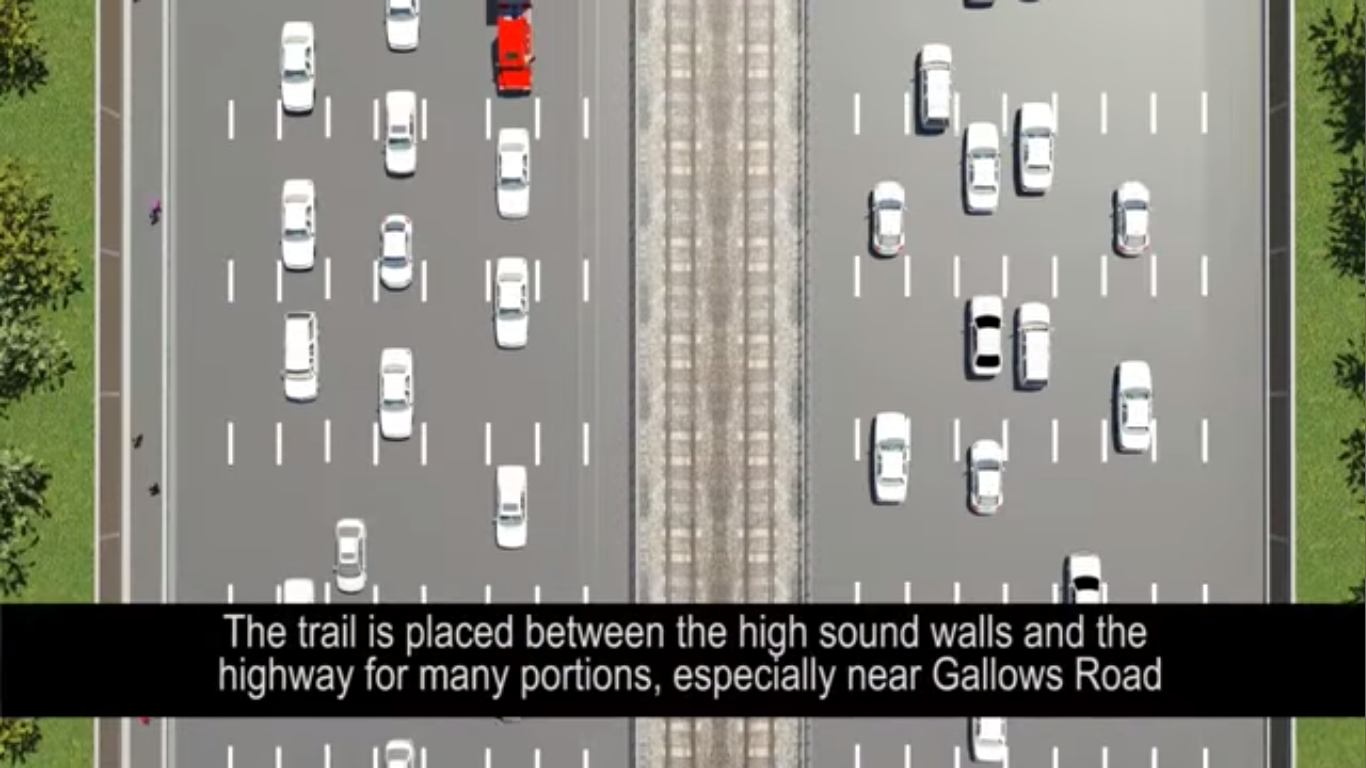

Anderson isn't kidding when he says shoehorned. Widening a highway in a developed area often involves taking nearby land, and I-66 is no exception. Under pressure to keep the takings to a minimum, the project is cramming its 12-foot bike path between a sound barrier and moving traffic. The trail would double as a utility access right-of-way for the highway.

As illustrated by a video rendering from FABB, trail users would be right up next to traffic. Anderson noted that although the state studied the impact of noise and pollution on nearby residents, it didn't quantify the impact on trail users, who would be even closer to the highway. At the very least, he wants a better barrier between cars and the bike path, like the transparent fence on the Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac River.

Because it's on the wrong side of the sound wall, connections to nearby streets are limited, and trail users who do brave the path might feel boxed in. But convincing the state and nearby residents to build a path on the other side of the sound wall could be difficult.

“We want the best trail we can get, and we’re cognizant of the neighborhood residents’ concerns. And we think it’s a really heavy lift to get it outside the wall," Anderson says. "If it’s going to be inside the wall, they’ve got to do everything to make it safe."

Public meetings on the plan are taking place this week, and Anderson expects feedback to continue over the summer until final design gets underway in the fall. He's already planning a ride along a nearby bike path with one of the project's designers to show him what works and what doesn't.

We'll see in the coming months if the state is willing to design a bike path worth riding, or if it's just squeezing it in because it's required. As Canaan Merchant writes at Greater Greater Washington:

For a trail that could connect hundreds of thousands of people in dozens of neighborhoods, it is critical that we make sure we follow best practices and design trails that are well made, useful, and not just an afterthought meant to get the environmentalists off of VDOT's back.

“They know how to build good trails," Anderson says of VDOT. "Why would we want to build something that people won't use? Let’s build it the best we can.”