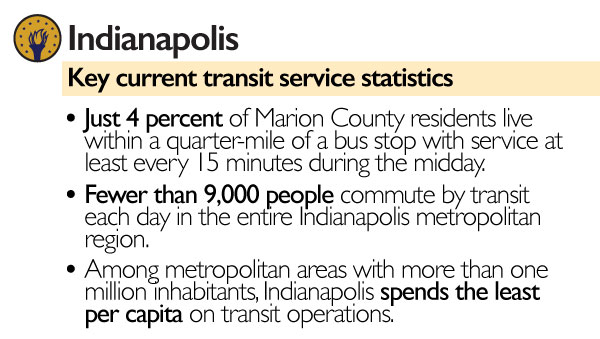

There are few places in the U.S. where transit ridership is as low as Indianapolis. Regionally, less than one percent of commuters -- about 9,000 people -- travel by bus each day, according to the U.S. Census. The vast majority of people drive to work alone, despite the fact that car ownership must be a financial burden for many -- more than 20 percent of the city’s population lives in poverty.

Suffice it to say that it’s simply not convenient for most people to use the Indianapolis transit system. Things are looking up, though: Last fall, Indianapolis residents voted massively in favor of a funding package that should significantly improve service in the coming years.

Next up in the Getting Transit Right series, I’ll be delving into what’s wrong with transit service in Indianapolis and identifying key reasons why few people get on the bus, before looking at how the new funding can build ridership.

Scarce transit service

Kim Irwin, who heads up the Indiana Citizens’ Alliance for Transit, didn’t mince words. "You have to choose to ride it for reasons other than convenience," she said. Curtis Ailes, a former writer for local blog Urban Indy, agreed: "It’s difficult to use the bus."

Indianapolis’ transit system, IndyGo, carries about 33,000 riders a day within Marion County, which since 1970 has been a merged government (sometimes referred to as Unigov) with the city of Indianapolis. IndyGo is a Unigov agency funded primarily through local property taxes, federal and state support, and fares. Currently, it provides one type of service: local buses.

The IndyGo network is largely a hub-and-spoke model, with lines extending from downtown -- sometimes referred to as the Mile Square -- in all directions. That makes some sense, given that downtown has a heavy concentration of jobs, including the seat of state government, a Purdue University campus, and several major corporations. There's also a convention center and an NFL stadium.

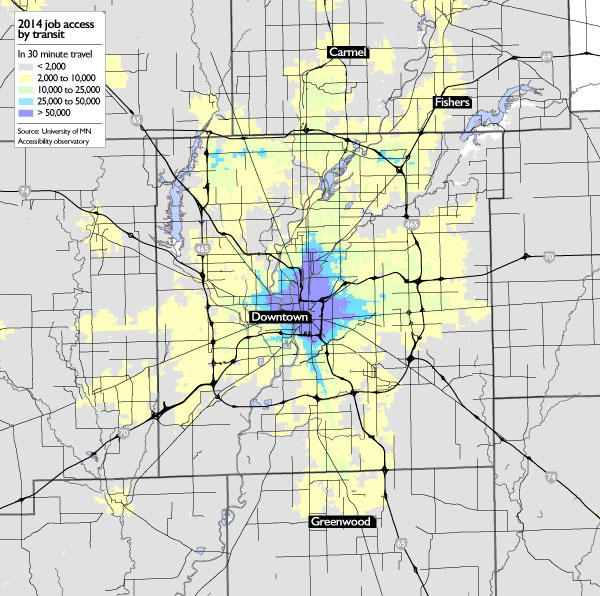

Despite all the jobs downtown, it's not easy to get there on a bus unless you live in one of the neighborhoods immediately nearby. As indicated in the following map, derived from the University of Minnesota Accessibility Observatory, in most of Marion County, residents can reach fewer than 25,000 jobs via transit in 30 minutes or less:

There are two primary reasons why IndyGo’s network doesn’t offer great accessibility. One, the buses stop frequently, which slows them down. The 39 bus, for example, is scheduled to take 68 minutes to travel its 13-mile route at rush hour -- just 11.5 mph.

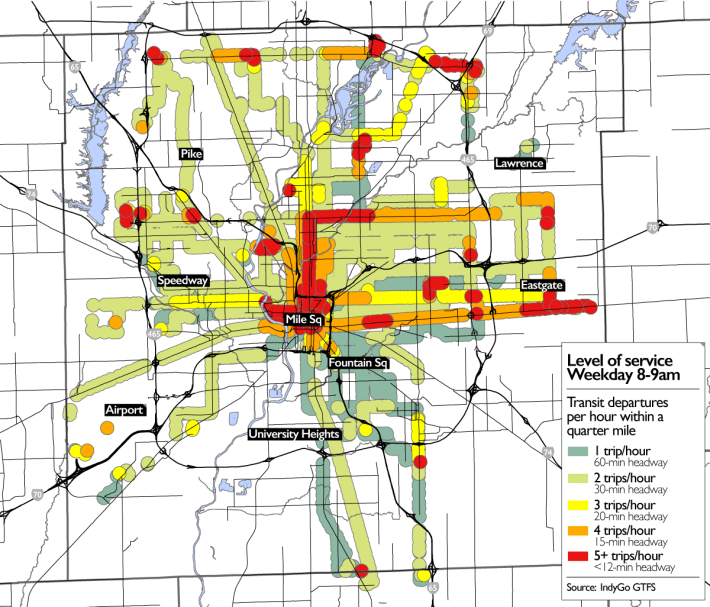

Perhaps more importantly, buses simply don’t show up very often. “If you live outside the old city,” Ailes told me, “the service is much less frequent and hard to depend on.”

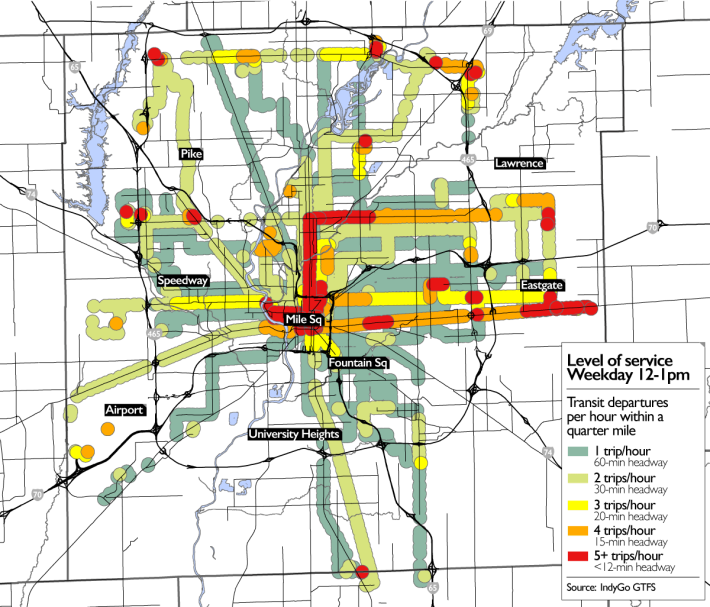

The following two maps illustrate the availability of frequent bus service in Indianapolis. Even at the morning peak -- from 8 to 9 a.m. on weekdays -- most of the city, if it gets bus service at all, sees buses no more than every half hour.

Indeed, of the county’s more than 900,000 residents, just 10.6 percent live within a quarter-mile of a bus stop with service at least every 15 minutes during rush hour. Only 4 percent, or 37,000 people, live within a quarter-mile of a bus stop with 15-minute service between 12 p.m. and 1 p.m. on weekdays.

In other words, it’s hard to use the bus because you can't count on a bus showing up when you need it.

Abundant highways

At the same time, driving is cheap and easy. "We don’t have a lot of traffic," said Mark Fisher, a vice president of the Indy Chamber, the local chamber of commerce. Indeed, with a jumble of freeways headed every-which-way from downtown and even a full-scale loop expressway circling the city, there is little reason for people not to drive.

The data bear this out. Almost 72 percent of Indianapolis commuters have travel times to work of less than 30 minutes, according to the U.S. Census. The vast majority of people own cars.

The lowest spending on transit service of any major American metro region

The fundamental reason why Indianapolis doesn't provide the bus service a city of its size should have is that it doesn't pay for bus service. In fact, the National Transit Database shows that of the 42 regions in the country with more than a million people, Indianapolis comes in dead last in per-capita transit operations funding at just $43 per person in 2015, or about 12 cents per resident per day.

“It’s a chronically underfunded, under-resourced system,” Irwin told me.

Mike Terry, president of IndyGo, openly stated that "we’ve been struggling for decades." The situation has been especially bad since 2004, when the agency cut 20 percent of its routes and increased its fares.

Grading Indianapolis transit service

With virtually no one riding it and poor service for those who do, Indianapolis needs a lot of work to improve the conditions of its bus system.

Strengths

- Little congestion means buses don’t get stuck in traffic much.

Weaknesses

- Very few city residents have access to reliable, frequent, all-day transit.

- Local bus services haven’t been adapted to modern standards and stop too frequently.

- Job accessibility by transit is low outside of the central area.

- Overbuilt freeway network puts transit at a disadvantage.

- Operations funding has been persistently low.

Coming next

Next week, I’ll explore land use in Indianapolis and how it affects transit ridership. IndyGo’s transit service district is huge, extending from downtown into farmland. Compromising between these areas makes providing effective service difficult.