In the last few years, it seemed like Detroit and its suburbs had shaken off the deep anti-urban pathologies that had always stood in the way of a robust regional transit system.

Almost four years ago, officials from the Detroit region won state permission to establish a regional transit authority (RTA), the result of a heroic effort. It was the first step toward fixing a transit system in crisis.

Detroit's transit problems go beyond its woefully underfunded system with no dedicated revenue stream. That weakness is exacerbated by regional dysfunction. Unlike most other regions in the country, Detroit and its suburbs have maintained a bifurcated system of suburban and urban transit networks, creating all sorts of hurdles for riders, like indirect routes and too many transfers.

In 2012, Detroit and its suburbs formed the RTA, following 40 years of effort and 23 failed attempts. This year was supposed to be when that cooperation really began to pay off. The RTA board, which consists of members from the city of Detroit and the suburban municipalities, plans to seek voter support in November for a property tax increase that will raise $2.9 billion over 20 years to build a respectable four-county transit system.

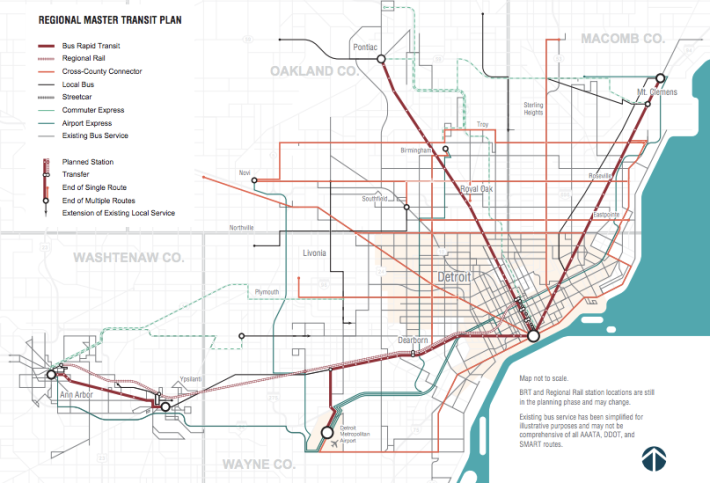

The RTA has been developing its plan for regional transit for months. The major pieces are three bus rapid transit lines that would connect Detroit to major job centers in the suburbs.

But now Oakland County Executive Brooks Patterson -- Detroit's famously self-styled "sprawl king" -- and Macomb County Executive Mark Hackel are threatening to scuttle the whole effort, reviving the ugly, racially-charged dysfunction that has devastated central Detroit.

Last week Patterson and Hackel threw the whole process for a loop by refusing to sign on to the ballot measure. Without their approval, it can't be put to voters in the fall.

Patterson has made a long political career in the region from playing the sprawling, affluent, mostly white suburbs of Oakland County off poorer, mostly black Detroit. He has a long list of complaints about the transit plan, but his main objection seems to be that 40 communities in that area -- mostly low-density bedroom communities -- would be "left out."

Joel Batterman, a coordinator with Motor City Freedom Riders, said the complaint is unfounded -- especially considering that state law requires 85 percent of the revenues generated by each county to be returned to that county.

"Oakland County receives the single biggest transit investment under the plan," Batterman said.

The Detroit Free Press has pointed out that the $1 billion widening of Interstate 75 that Patterson has championed is paid for by residents of Detroit and other urban communities but pretty much exclusively benefits Oakland County. But he applies a selfish double-standard to transit.

In a scathing editorial, the Detroit Free Press called Patterson and Hackel's unexpected about-face an "erroneous dog whistle, meant to evoke the bad old days of rancor and antagonism in the region."

"This is a dollar-down rebuke of the region’s neediest citizens, at the precipice of hope for something better," wrote the paper's Stephen Henderson.

As discouraging as Patterson's obstructionism is, it may be the last gasp of a dying political order.

As noted by the Detroit Free Press, Patterson is facing a challenger who explicitly rejects his anti-urban agenda. Batterman says there's a growing tension not just between Detroit and the northern suburbs, but the uppermost parts of Oakland County and the increasingly urbanized southern half, where many of the region's big job centers are located.

If Patterson and Hackel can somehow be persuaded to change their minds before August 16, the transit measure can still land on the ballot this year. If it does, polling suggests the measure would have a strong chance of passing.

"I think that's one of the reasons transit has never been allowed to come to a vote in the region," said Batterman. "Some folks might be afraid people might actually vote for it."