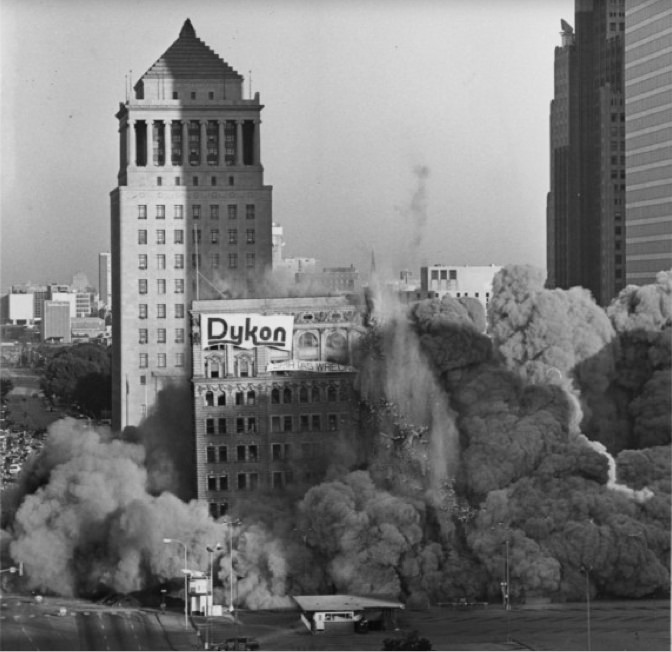

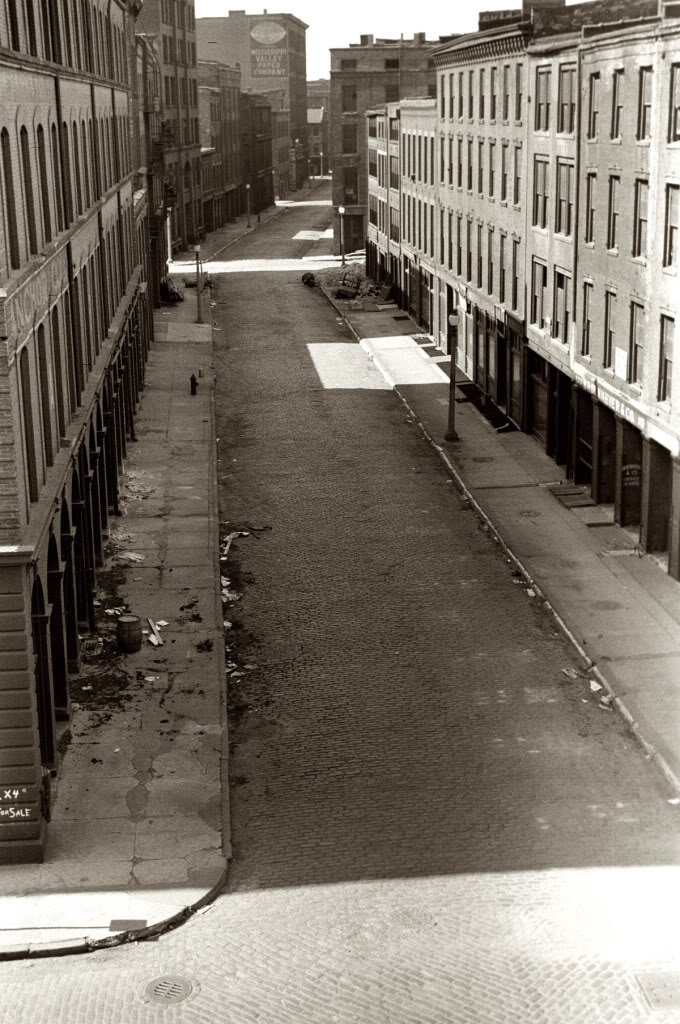

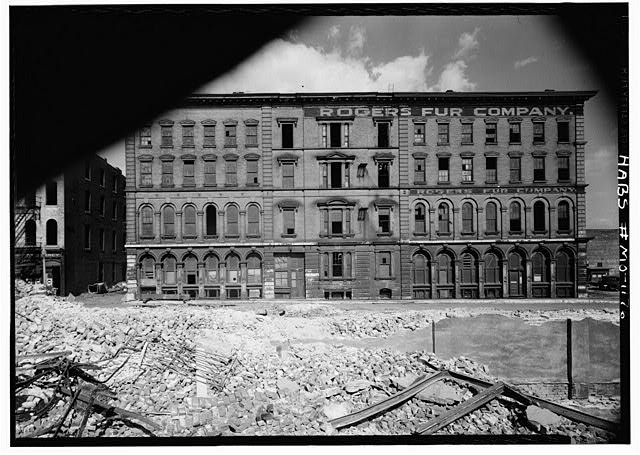

Some of these images, dug up by Alex Ihnen at NextSTL, almost look like a war zone. Buildings exploding. Entire city blocks reduced to ghost towns. Families out on curbs, carrying all their belongings in suitcases.

It wasn't a war, though -- it was mid-century St. Louis. Perhaps no other American city more enthusiastically embraced the development strategy known as "urban renewal," a euphemism for wide-scale demolition to clear land for rebuilding on a blank slate. Today we look back on this era as a moral and social catastrophe of our own government's design.

Urban renewal's fiercest critic was Jane Jacobs, who was born 100 years ago this week. In recognition of Jacobs, Ihnen unearthed these images of the urban renewal era that she rebelled against, complete with scenes of powerful, confident men standing around neat little models. They are pretty remarkable.

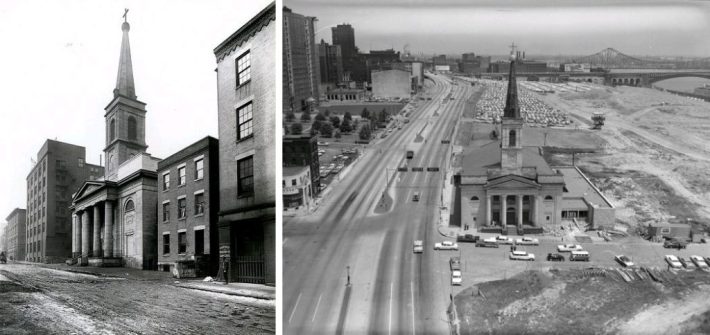

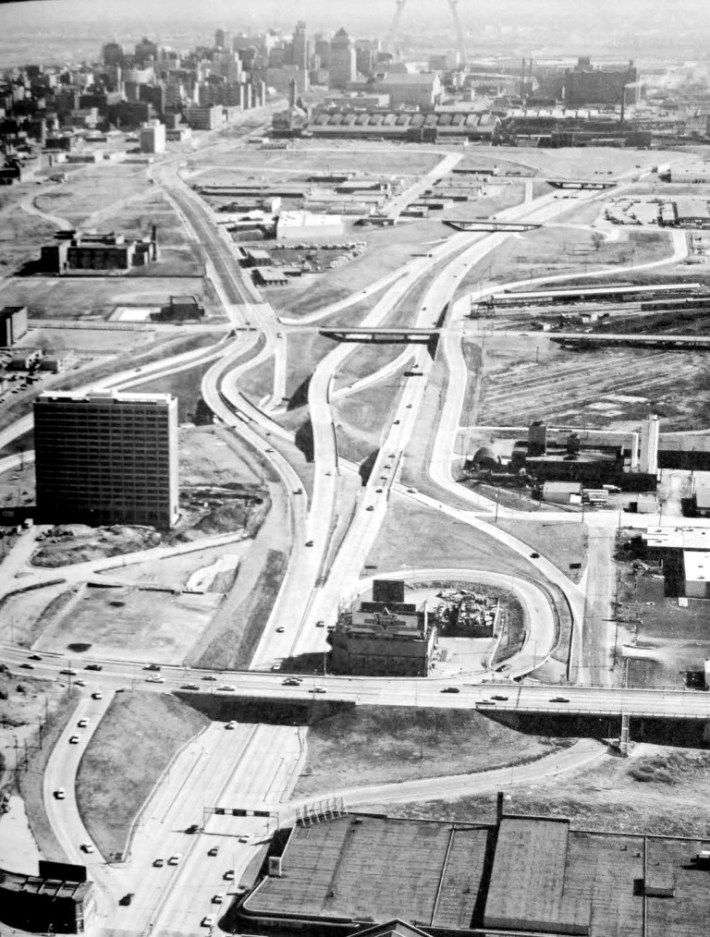

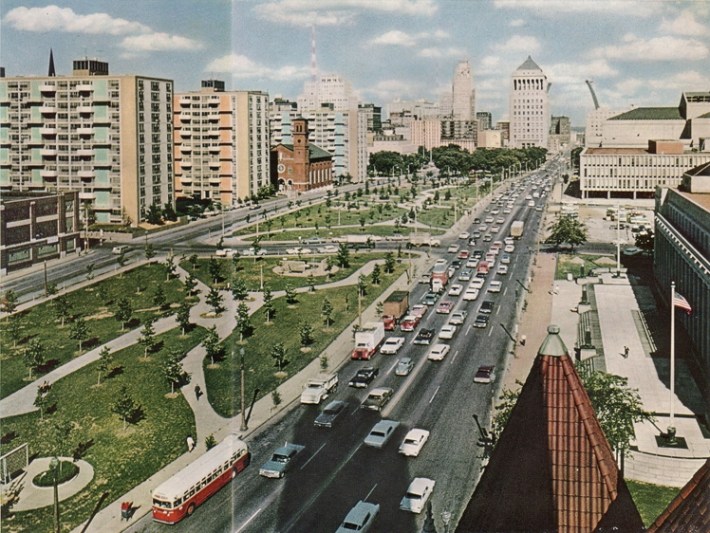

Of course, much of the destruction was to make way for a car-based city. Here are a couple of particularly heinous examples:

Urban renewal wreaked an enormous human toll. An estimated 1 million people in 993 neighborhoods across the U.S. were forced to relocate by urban renewal policies, most without any compensation. A disproportionate number of them were poor or black. Here is one family in St. Louis who were uprooted.

Here are the "visionaries" behind Pruitt-Igoe, the gigantic housing project that later came to stand for everything wrong with the towers-in-a-park model. In Death and Life, Jacobs wrote about why the variety and fine-grained detail of city streets matter -- qualities that were swept away here to make room for monotonous buildings and sterile green space. The scene of planners toying with neat, orderly models, oblivious to the effect on actual people, captures the antithesis of what Jacobs stood for.

As Ihnen notes, "people did fight back. Residents did oppose demolition. Activists did go to the courts and seek relief and the protection of their rights." But the legacy of urban renewal has been tough to overcome. St. Louis has lost 63 percent of its population since 1950.

These photos powerfully evoke what Jacobs fought against and remind us that it's the street-level, human details that make a city great, not mega-projects imposed on a map.