The same team that helped overhaul Houston's bus network is turning its attention to the city's bike network.

This week, recently-elected Mayor Sylvester Turner unveiled the city's first bike plan since 1993. The plan envisions a network of low-stress bikeways -- a welcome improvement over Houston's previous bike plan, from 1993, which mostly consisted of "share the road" signs and sharrows on wide, high-speed roads, according to Raj Mankad of OffCite, a blog of Rice University's Design Alliance.

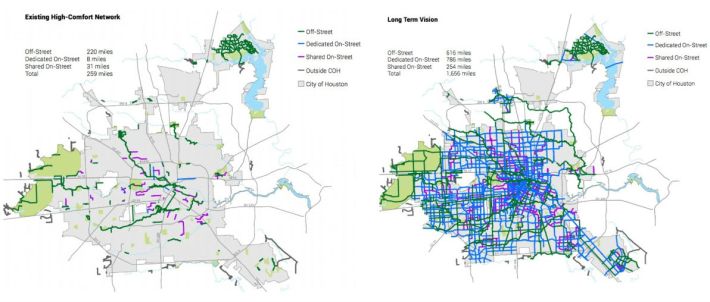

In 2012, Houston voters backed the creation of the Bayou Greenways network, 150 miles of linear trails along the city's low-lying bayous. But without on-street connections, the greenways would be fragmented and people would have to bike on dangerous streets, writes Mankad.

The new plan calls for about 800 miles of on-street bike lanes -- up from just 8 miles today -- and about 400 additional miles of off-street paths. Though the plan doesn't give a concrete timeline for completing the network, the goal is to achieve "gold-level" status from the League of American Bicyclists by 2026.

The estimated cost would be between $300 and $500 million. To put that in perspective, the pricetag is at most one-tenth of what the region is pouring into the "Grand Parkway," a third ring road for the region.

The plan was designed by a lot of the same people who worked on the bus network redesign: the engineering firm TEI, Morris Architects, and Asakura Robinson.

Now that the city has a better bike plan, things will get interesting, Mankad writes:

Seeing plans like these gives rise to a mix emotions. Elation for the ambition and the potential of the plan. Relief that our experiences are named, that the terrifying stretches of road that ruin an otherwise beautiful, cost-effective, energy-efficient, environmentally sound experience are recognized. Sadness and grief for those who have died or been maimed at many of the spots where interventions are planned. We also struggle with cynicism that, even if this plan is adopted, it will not be implemented. And we worry that Houstonians will react with a mindset of scarcity, believing that a better bicycle network means less space for those in cars, or believing that paying for these infrastructural improvements and investments in mobility means less money for other ones.

For the city to become a safe place for bicyclists, for the city to become one where the "interested and concerned" of the population not only begin to imagine themselves on a bicycle but feel free to use the city with the power of their own legs, for the city to continue to attract those who are less and less interested in owning cars, both the forms of our streets and the norms of our behaviors need to change. And that will take messiness and dialogue. This is the beginning.