This story has been updated to reflect comments and clarifications from the FHWA.

Secretary Anthony Foxx has made clear that safety -- and specifically, safety for bicyclists and pedestrians -- is a priority of his administration. If that’s true, his administration sure has a funny way of showing it.

The Federal Highway Administration's proposal on safety performance measures allows states to fail to meet half their own safety targets without consequences. And it gives the seal of approval to worsening safety performance as long as people in that state are driving more.

The MAP-21 transportation bill was cheered for instituting performance measures, but it left it the details up to U.S. DOT. The first of three Notices of Proposed Rulemakings -- U.S. DOT’s proposals for how to set up this system of accountability -- was released earlier this week. This one is on safety; the next two will be on 1) infrastructure condition and 2) congestion and system performance. These rulemakings are slipping behind schedule but were always expected to be implemented well after MAP-21 expires September 30.

People on foot and on bikes "left out"

First, bike and pedestrian advocates are bitterly disappointed that their demand for a separate performance measure on vulnerable road users was not included. “Once again, bicyclists have been left out,” said Bike League President Andy Clarke in a blog post Tuesday. “We know that without a specific target to focus the attention of state DOTs and USDOT on reducing bicyclist and pedestrian deaths within the overall number -- we get lost in the shuffle.”

DOT is requesting comments on how a performance measure for bicyclists and pedestrians might be possible, but also makes clear it's unlikely to implement one. The agency says that “separating specific types of fatalities... leads to numbers too statistically small to provide sufficient validity for developing targets.”

We've asked FHWA for comment for this story. We'll update when we hear back.

"This proposal is a solid first step in ensuring states use a data-driven approach to improve safety for everyone who uses the road," said a spokesperson for FHWA. "We look forward to receiving comments and developing a new rule that will reduce traffic fatalities and serious injuries on all public roads.”

UPDATE: In a March 19 webinar, an FHWA official said that this month, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and the Governors Highway Safety Association negotiated the possibility of a bicycle fatality performance measure as one of the new measures, "and that will begin, hopefully, in FY2015."

50 percent failure = A for effort

The only four performance measures FHWA is requiring are: 1) number of fatalities, 2) rate of fatalities, 3) number of serious injuries, and 4) rate of serious injuries. States can choose to add separate targets for urbanized and non-urbanized areas.

Things go from bad to worse in Section 490.211: “Determining Whether a State DOT Has Made Significant Progress Toward Achieving Performance Targets.” Here, it becomes clear that FHWA intends to let states skirt accountability entirely.

Since FHWA recognizes that many factors “could be outside of a State DOT's control,” they propose deeming progress acceptable if states meets -- or at least makes "significant progress" toward -- 50 percent of their targets, or two of the four. Acceptable progress means the state won’t have requirements placed on its use of Highway Safety Improvement Program safety money.

Note that FHWA “seeks comment on whether 50 percent is the appropriate threshold for determining if a State has overall achieved or made significant progress toward achieving its performance targets.” The agency is holding a web forum Monday.

Safety targets are meaningless

If a state fails to meet a target, it would then be evaluated to determine whether it has at least made "significant progress." Only if a state fails to meet more than half its targets -- three out of the mandated four -- would it then get evaluated. At that point, the basis of the evaluation is no longer the stated target but the state's own historical trend line over the last 10 years. As long as the state's actual performance was within a 70 percent “prediction interval” of the 10-year trend line, it's given a pass.

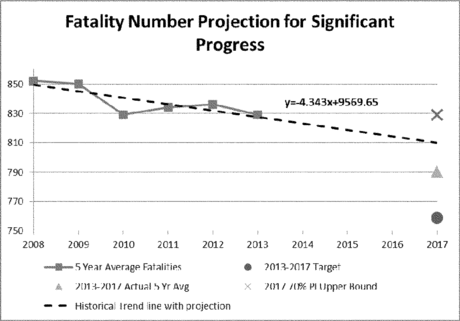

In the fictional example FHWA gives, if a state sets a target of 759 fatalities but actually has 769, they would look at the trend line.

In this case, the trend line, plus the "prediction interval" sets the upper bound of the acceptable number of fatalities at 825.66. So despite the fact that this fictional state has a new seat belt law and set a goal for itself of reducing fatalities to the still-astronomical number of 759, FHWA says not only is it totally fine to have 10 more people die on the road than planned; it would have been fine to have 66 more people die on the road than planned.

If these performance measures were intended to keep states accountable, it appears they're a long way away from achieving that goal.

Meanwhile, FHWA notes that there will be a long time lag in assessing performance, since it will be using data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System and the Highway Performance Monitoring System: “The FHWA must wait 3 years, until [calendar year] 2020, to assess whether CY 2017 targets were achieved because the FARS and HPMS data are not available until that time." Presumably, it would then take another year for states to change course in an attempt to remedy the situation.

More people dying? No problem -- just keep driving!

Let’s go back to those four simple performance measures to examine the next major problem with FHWA’s approach: Two of the four measures look at the “rate” of serious injuries and fatalities, based on vehicle-miles traveled.

Those measures don’t remotely represent people on foot or on a bicycle, for whom vehicle-miles traveled is meaningless. And worse, states can hide increased fatalities by increasing VMT, an outcome that helps no one. But since a state needs to fail three of the four required categories to even warrant evaluation, it means fatalities and injuries can increase so long as VMT is going up.

As an FHWA spokesperson noted, the requirement to reduce fatalities and injuries per vehicle-mile-traveled was set by Congress in MAP-21, and so the agency is merely implementing Congress's vision.

UPDATE: In the March 19 webinar, an FHWA official said that while they can't express monetarily all the benefits of the proposed rule -- including better decision-making, greater accountability in the use of federal funds, and progress toward the national goal for safety -- they do use a break-even analysis to figure out at what point the quantifiable benefits would justify the costs of the new safety protocol. The answer: The rules would need to prevent less than one fatality or 15 injuries each year across the country to be worth the costs.

Timing

This safety approach, anemic as it is, is still a long way away from implementation.

The FHWA has opened up a 90-day comment period on this rulemaking. The agency has said it wants to wait until all three rulemakings are complete to begin implementation, in spring 2015 as a best-case scenario.

MAP-21 was celebrated for ushering in an era of reform based on performance and accountability, but judging by the way FHWA proposes to run the program, it will prove to be anything but.