Gawker dished out some richly-deserved ridicule to Tennessee State Senator Jon Lundberg yesterday, following reports that he is co-sponsoring legislation to outlaw the specific speeding camera that nabbed him doing 60 in a 45 zone last October. Lundberg denied that the incident had any impact on his decision to sponsor in the legislation, and contested the violation to boot.

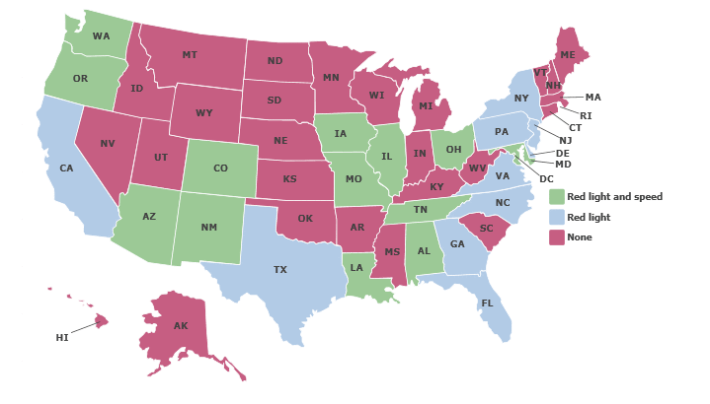

But the case is a telling one. State governments around the country have demonstrated hostility to automated enforcement programs. Twelve states specifically forbid the use of speed enforcement cameras, except in very limited circumstances, according to the Governors Highway Safety Association. Nine states prohibit red light cameras. Others, like New York, have yet to enact legislation that would enable cities to use these traffic enforcement tools.

A proposed ban in Iowa failed narrowly in the Senate last year and one is currently under consideration in Ohio.

The Ohio legislation, framed as a defense of due process and privacy, has received mostly favorable coverage in the press and has enjoyed the support of groups like the Ohio ACLU and Ohio PIRG. One Ohio PIRG official characterized speed cameras as "cash cows designed to rip off drivers." Ohio Lawmaker Ron Hood went so far as to assert that red light cameras are themselves a safety hazard.

Adrian Lund, president of the Insurance Institute on Highway Safety, told the Washington Post last year that these kind of debates tend to get distorted: “Somehow, the people who get tickets because they have broken the law have been cast as the victims.”

Lost in these debates is the fact that automated enforcement saves lives. A 2011 study by IIHS comparing cities with red light cameras to those without them found that in the 14 largest U.S. cities, the cameras reduced fatal red-light-running collisions by 24 percent. Even more impressive, they seemed to promote safe driver behavior more generally. The researchers found that cities with red light cameras saw 17 percent fewer fatal crashes at signalized intersections, per capita, than cities without cameras.

Between 2004 and 2008, that added up to 159 lives saved in those 14 cities alone. If automated enforcement had been installed in all 99 of the U.S. cities with populations over 200,000, some 815 lives would have been saved over those four years, the report found.

Russ Rader, vice president for communications for the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, calls the backlash "a lot of hot air from a vocal minority." According to Rader, the debate about whether traffic cameras improve safety is settled.

"Study after study demonstrates that automated traffic enforcement works to make streets safer," he said.

As for the claim that speed cameras are unsafe, Rader says that's simply "not true."

"That’s not supported by any of the research that has been done by traffic safety experts, the federal government, and universities," he said.

A few studies have found that red light cameras do increase rear end collisions, but the data is not consistent. In addition, these types of collisions tend to be minor fender-benders, which pose far smaller risks than the type of high-speed, side-impact collisions that the cameras prevent, says Kara Macek, a spokeswoman with the Governors Highway Safety Association.

"I know it’s a contentious issue," she said. "But typically the arguments against it -- 'It’s a revenue generator,' 'It's a privacy concern' -- are outweighed by the safety benefits."

Macek's organization recommends some precautions that can help communities avoid controversies like the one in Ohio. Macek says cameras should only be installed in problem areas, like dangerous intersections, and only after a public information campaign. The GHSA also recommends that all revenues from the ticketing be returned to programs that improve street safety.

Macek added that the cameras are an important tool for communities, especially as resources for law enforcement become more strained.

In Ohio, irate drivers have tended to drown out messages like that. But local governments, law enforcement agencies, and victims' advocates have testified that an outright ban on automated traffic enforcement would be a major setback.

Officials from the Toledo Police Department reported a noticeable decrease in traffic collisions after the cameras were installed. The city of Akron, which instituted the program after a 10-year-old boy was killed, uses the cameras only in school zones. All of the half million dollars generated was used to support child safety programs in that city, officials say.

Meanwhile, at a recent hearing in Columbus, Sue Oberhauser, co-chair of a national group that advocates for traffic safety, spoke for victims who can't testify -- including her daughter, who was killed by a reckless driver.

"If our daughter Sarah could be here today, she would ask each of you, 'What about my right to live my life and raise my children?'" Oberhauser said, according to a report in the Plain Dealer. "She cannot be here today because she was killed by a man running a light at 55 miles per hour."