Drivers turning left are a leading cause of pedestrian crashes in urban areas. Where drivers can only turn left with a green left-turn arrow, pedestrians are more protected. But when drivers are watching oncoming traffic for a chance to make their turn, they tend not to be as vigilant as they should to watch for pedestrians. In fact, 5 to 11 percent of drivers don’t look for pedestrians in the crosswalk at all.

Two Oregon researchers observed people’s behavior and eye movements as they operated a driving simulator to see if they noticed pedestrians. David Hurwitz from Oregon State University and Christopher Monsere from Portland State University found that danger increased with more cars and fewer people walking. There is safety in numbers: The more pedestrians there are, the more drivers pay attention. But if there are more cars, they take up more of the drivers’ attention.

It’s no surprise that drivers’ attention is compromised when they have to watch oncoming traffic for a chance to turn. One solution is to prohibit left turns except with a green arrow -- a "protected" left -- instead of letting drivers pick their own moment with a "permissive" left turn signal -- a circular green or flashing yellow, for example.

Michael Ronkin, a former Oregon DOT bike/ped coordinator who now lives in Europe, said “permissive [non-dedicated] left-turns are extremely rare in urban environments” there, with far better pedestrian safety as a result. “[The] clear message in the U.S. [is that] moving cars is more important than protecting people not in cars,” he said.

Pedestrian advocates also favor a signal phase exclusively for people on foot, such as a Barnes dance, where pedestrians can cross in all directions, even diagonally, and all traffic is stopped.

But are dedicated signals the solution?

“The downside of protected or leading lefts is that it adds another phase to the signal, and means that ‘through traffic’ will sit stopped at a red light longer than if left turns shared the green time with through traffic,” said Gary Toth, a former New Jersey DOT official. “The more complicated the signal phasing gets, the more that the traffic signal ‘clogs’ up the intersection.”

That’s not just a problem for drivers. Pedestrians have less time to cross, too, in that scenario, and may have to wait longer. And the longer pedestrians have to wait, the more likely they are to violate the don’t walk signal, according a 2011 study by Wuhong Wang.

Either way, Toth says, pedestrian safety isn’t what drives engineers to install one kind of signal over another. “There are protocols that traffic engineers use to decide whether to include them or not, and it mostly has to do with whether there is so much traffic during peak hours that cars couldn't make a left without their own phase,” Toth said. “I have never heard of anyone thinking about pedestrians in making this decision.”

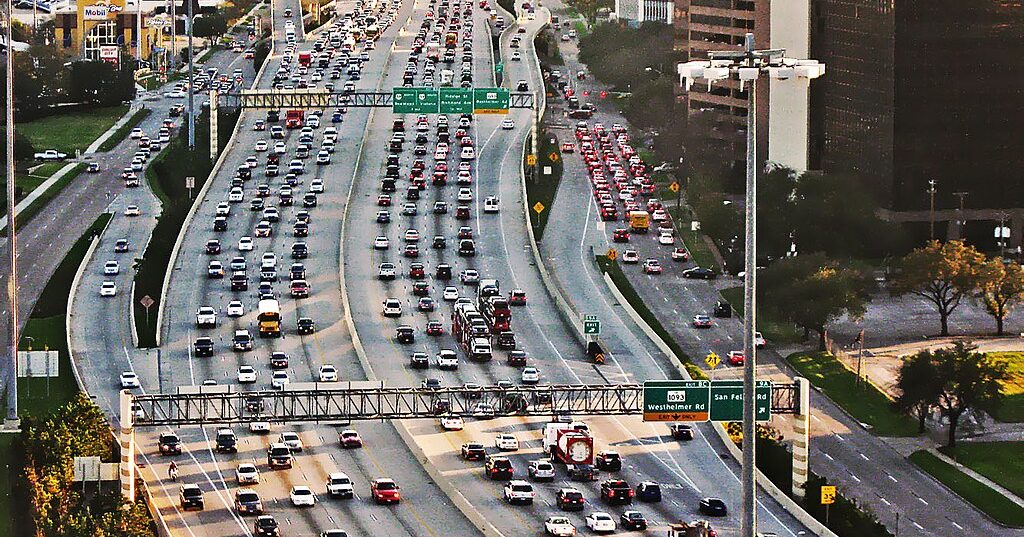

The solution will be different for different contexts. In a heavy pedestrian environment, a Barnes dance could be a good solution, like in DC’s Chinatown, where one was implemented in 2010. But places like that are probably not where pedestrians are most at risk, since the presence of more people walking commands drivers’ attention. It’s the big, suburban arterial roads with high traffic levels and few people on foot where drivers simply aren’t looking for pedestrians. Does it make sense to have a dedicated signal phase for pedestrians when nine times out of 10 there won’t be any? And when the odd pedestrian would likely end up having to wait so long for a walk signal that he’d be tempted to chance crossing against the signal?

Maybe the problem isn’t how we design roads but how we design communities, Toth said. Planners put schools and shopping on big arterial roads that are designed to be high-speed thoroughfares for long-distance drivers and commuters. They fail to create connected grids for local activities. The result is wide, inhospitable roads with monster intersections, multiple turning lanes, and dizzying traffic levels – and then, says Toth, “we call the engineers idiots because they can't figure out how to get the pedestrians safely through this environment.”